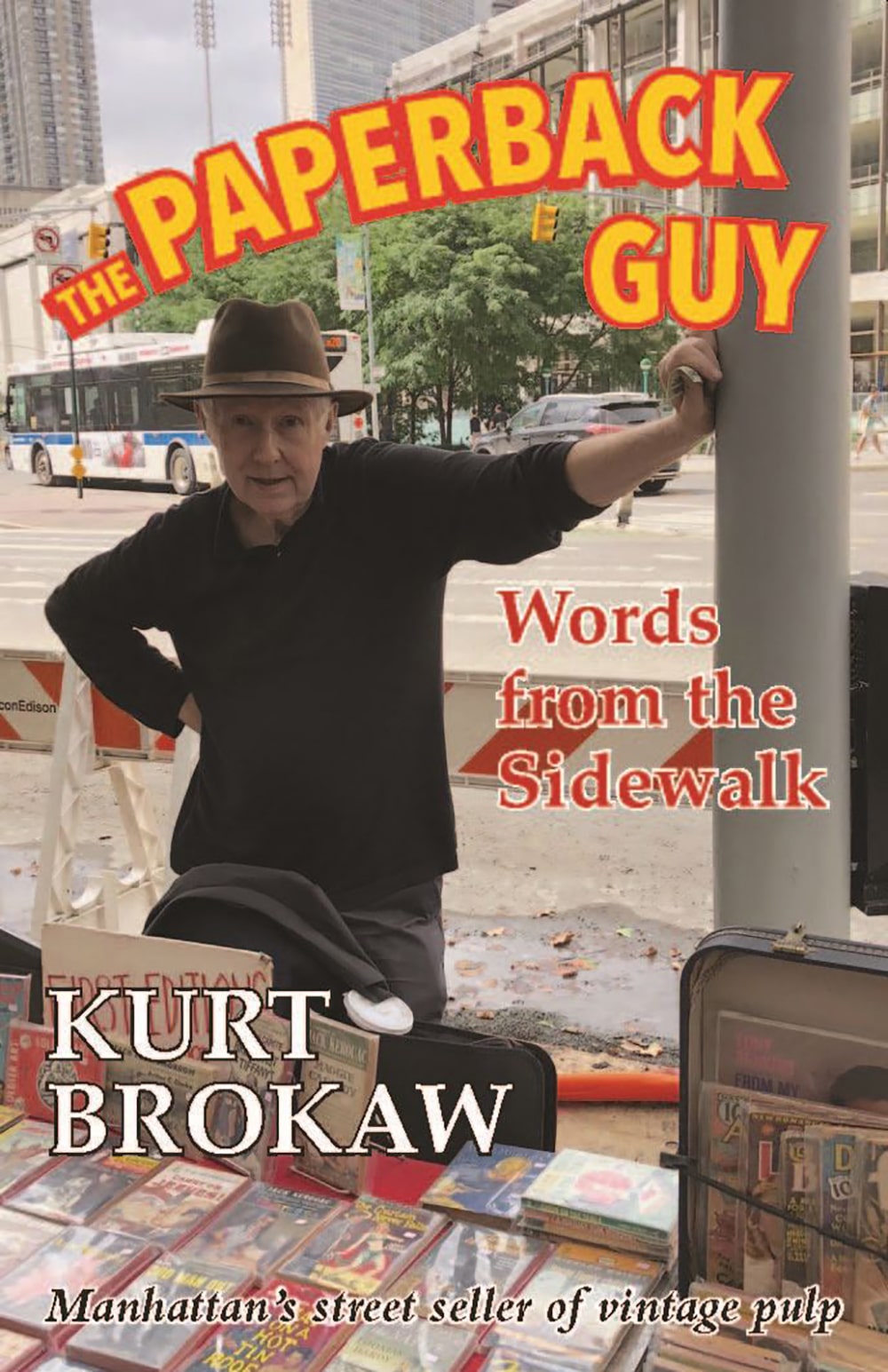

Review of The Paperback Guy: Words from the Sidewalk by Kurt Brokaw

For over thirty years of Sundays, Kurt Brokaw has hauled a table to Broadway (somewhere between Lincoln Center and specialty food store Zabar’s) to set up shop on the sidewalk. He’s there to sell his collection of pulp fiction magazines and vintage paperbacks from the ‘40s and ‘50s. From 8AM-8PM, in his trademark fedora, Brokaw sits on a stool, picks up a magazine, and waits.

The Paperback Guy: Words from the Sidewalk (available from Small Press Distribution, spdbooks.org) is both a fascinating testament to Brokaw’s passion and a concise history of the genre. Brokaw begins by making some important distinctions. “Pulp fiction magazines and vintage paperbacks are not the same thing,” he explains.

“Pulps” preceded women’s glossy magazines and were printed on cheap, ragged paper (hence the name). Sold for a dime at newsstands, these magazines gave some of the 20th Century’s best-known writers (including Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Ray Bradbury) their start. Pulps evolved into novels for economic reasons. “Publishers sensed there was a far wider market for novels at a quarter than for short-story pulp magazines at a dime,” Brokaw writes.

What pulps and paperbacks have in common is their distinctive cover art: paintings that are at once colorful, dramatic, and suggestive. Brokaw notes that “glamour gals of the era were often drawn to resemble Lana Turner.” Color photos highlight a few of his favorites.

Today, Brokaw can sell a title from between $15-$1,000. With most of the New York City’s specialty bookstores closed (well before the COVID-19 pandemic), there’s no competition, and exempting bus fare and a cup of coffee, little overhead. Brokaw doesn’t take credit cards, own a mobile device, or hand out business cards.

As an outside vendor, Brokaw must contend with the weather, the occasional dog lifting a leg against the edge of his table, a bird relieving itself overhead—and trying to find a place to relieve himself.

Most dispiriting of all? On any given day, he might not sell a thing. “There is not a living in this,” Brokaw warns, estimating that he’s ignored by about 95 percent of the people who pass by his table.

While the income that does trickle in allows Brokaw “to put a few steaks in the freezer,” he’s not in it for the money. A former ad executive, a professor at the New School for thirty-three years, and a teacher of film (especially film noir) at the 92Y (where I learned from him how “literature migrates onto the screen”), Brokaw continues to work as senior film critic for The Independent. Part of “a small band of rabid collectors,” Brokaw’s Sunday gig is a passion project. He finds that “the attraction of curating one table for 8 million people is irresistible.”

Born in Iowa in 1938, Brokaw recounts learning to read from pulps while his dad shot pool, building his collection as a teenager from “spinner racks in Rexall pharmacies and cigar stores.”

These stories of “tough guys and loose gals with too much past and too little future” seem to have deeply impressed themselves upon his sensibility. He’s become his own kind of New York character, one with a clear idea of who he is and what he values—along with what his rights are.

“People think bookselling is a First Amendment right. It’s not,” Brokaw writes. He points out that while anyone is free to publish something, the method by which it can be sold is determined by local government.

An obscure clause to an 1893 law “originally designed to protect Jewish immigrants who peddled chapbooks out of pushcarts in the hurly-burly of Orchard Street for a penny a copy”

allows Brokaw to sell written matter without a license (although he collects and pays New York sales tax). A surprising ally? The late mayor Ed Koch (his grandfather had been a peddler), who assured Brokaw that “as long as I’m in office, you’ll never have a problem selling your books.”

Also surprisingly, Brokaw writes that 95 percent of New York City’s sidewalks can still be used for this purpose of selling written material. Vendors can occupy a 4’ x 8’ space as long as it’s ten feet from a residential door, twenty feet from a business entrance.

While Brokaw hawks “a little bit of everything—classics, hard-boiled crime, science fiction and fantasy, romances, westerns, sports, gay/lesbian, African American literature, film tie-ins, war-related fiction and nonfiction, children’s titles”—the main thing he seems interested in peddling is stories. “Sharing the stories is a great part of the value of an object,” Brokaw writes. Encounters with famous customers include Phillip Roth, the Beat writer Gregory Corso, Whoopi Goldberg, Madonna (“not once, but twice”), and a friend of Marin Scorcese who was shopping for a birthday gift for the director. Brokaw remembers little of meeting singer Rod Stewart, blinded as he was by the gorgeous woman on his arm.

Over the years, Brokaw’s witnessed changing tastes (less interest in sci-fi, more in queer pulp), but he reflects little on the greater changes to the city itself. Reading The Paperback Guy, you get the feeling Brokaw inhabits a self-created world, full of mystery and romance. Brokaw admits to imagining himself as a character in a story—no doubt populated by tough broads, hard-nosed detectives, smoky rooms, and Remington typewriters.

Brokaw, now in his eighties, has come to think of selling off his collection as a “going-of-life” passage. He seems equally resigned to reluctantly committing his story to paper (calling it his “gasbag narrative”). He only did so at the urging of a devoted customer—now his publisher, David Applefield.

Writing the book’s introduction, Applefield praises the kind of kismet that comes with secondhand shopping. “With used books, you never know what you’ll find. The joy goes deeper too in that you do not even know what you are looking for.”

It’s Applefield who points out that while these stories might be new to Brokaw’s customers, they are “stories that have been told countless times and whose pages have been turned silently in the past by anonymous fingers.” Perhaps those fingers continue to point and beckon, leading one to pick up a story that has a special resonance.

Brokaw is the middleman. But he isn’t just connecting authors and readers. He’s fostering a singular experience of accessing a unique past. This is a limited time offer. If these past few months have illustrated anything, it’s how quickly a way of life can vanish.

Should you find yourself on the Upper West Side some Sunday, look for the man in the hat sitting beside his table of books. There might just be a title that speaks to you. As Applefield sees it, “literature’s mission is completed via the courage and patience of the bookseller.”

Review by Michael Quinn