Review of TV Snapshots: An Archive of Everyday Life, by Lynn Spigel

Review by Michael Quinn

For a long stretch of years, I lived without a TV. What do you do at night?, people would ask me, more concerned than curious, as if there was only one thing you could do and one thing you needed to do it.

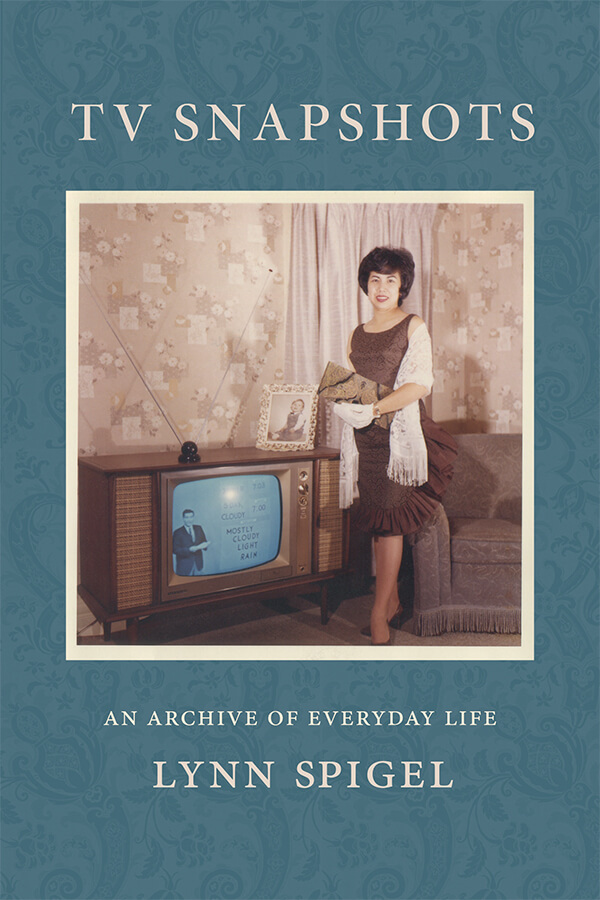

As it turns out, there’s something else people like to do with a TV besides watch it. They like to take pictures of it. TV Snapshots: An Archive of Everyday Life, by Lynn Spigel, thoroughly and engagingly analyzes a collection of amateur snapshots, from the 1950s through the 1970s, of people posing next to their TVs, to understand why.

Spigel, a professor of screen cultures at Northwestern University, has spent a decade collecting almost 5,000 photos of all kinds of people and their beloved TVs. “I have lost many bidding wars on eBay!” she laments. As an academic, Spigel is interested in the “invisible histories” pictures like these suggest: Who were these people, and what compelled the photographer to pose them by a TV? The size of Spigel’s collection makes it clear that this tradition was widespread—but how did it become so, not just for a family, but for a culture?

Clearly, the emergence and relative affordability of the snapshot camera played a huge role. Spigel unpacks the relationship of these “companion technologies”—TV and camera— to examine the impact of the “everydayness” of media on people’s behavior. After all, media is the source of a lot of our ideas on how to think, act, and behave. (It makes me think of how taking a selfie was once a new thing, but once those images starting cropping up online, a kind of conformity crept in. Eventually everyone started making the same kind of sexy pout—the infamous duck lips.)

Even now, entrenched as we are in our digital age, TVs are still a big part of American lives. They still take pride of place in most homes: just think of how most living rooms are set up to accommodate what’s best for them. While the size of your TV might be the most impressive thing about it now, in the beginning, just having a TV was a real status symbol. Some of the shots Spigel shares are portraits of early models: tiny, curved screens housed in huge wooden cabinets.

Over time, these behemoths became like any other flat surface in the house: a place to pile all of our crap. “Bric-a-brac tells a family story,” Spigel points out. In some photos, a TV is used as a pedestal to display something meaningful, such as a framed picture or a vase full of flowers. In others, what’s significant is the mess all around the TV: a tangle of cords behind it, a jumble of toys on the floor in front of it.

Spigel’s vast collection includes trick shots (such as a person standing next to a picture of themselves on the TV’s screen), glamour shots (both ladies and drag queens), and even sexy poses (a nude man lies stretched out on a couch, arms behind his head, with a copy of TV Guide over his, uh, remote control).

Fascinating as it is, TV Snapshots isn’t an easy-breezy read—nor is it meant to be. Spigel is writing for other academics (debating things like what constitutes an archive versus a collection), but any reader can find value in her thought-provoking ideas about media’s influence on racism and gender roles, and especially in the photos, a kind of cultural currency that trades in kitsch, camp, and a sentimental longing for the pre-digital age.

Spigel writes, “Television sets and snapshots of them are now part of a widespread analog nostalgia for nonconnected media things—things that came inside walnut cabinets, record sleeves, film cans—timeworn objects with noisy scratches, missing inserts, faded colors, flashed flashbulbs, and bent antennas searching for signals no longer in the air.”

The most surprising thing TV Snapshots gave me was insight into my own ambivalent relationship with television. I grew up in a house where the TV was always on. My father, who had two working parents in the 1950s, felt he’d been raised by it and found it comforting; I found myself competing with it to be seen and heard. By the time I left home, I’d had enough of the both of them.

At a certain point, friends, pitying my TV-free existence, gifted me with one. It sat untouched on a dresser. I never once turned it on. That might put me in the minority—but it puts me in some excellent company. In her memoir, Just Kids, singer Patti Smith recounts her experience moving into the Chelsea Hotel in 1969 with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe: “There was a sink and mirror, a small chest of drawers, and a portable black-and-white TV sitting on the center of a large faded doily. Robert and I had never owned a TV and it sat there, a futuristic yet obsolete talisman, with the plug dangling for our entire stay.” I’m sure there’s a picture of this somewhere, and I’ve no doubt Spigel will be the one to find it. Flip through TV Snapshots and you’ll get sucked right in.