Review of Another Day’s Begun: Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in the 21st Century by Howard Sherman

Review by Michael Quinn

“What is trivial and what is significant about any one person’s making a breakfast, engaging in a domestic quarrel, in a ‘love scene,’ in dying?” asked Thornton Wilder, reflecting on the question at the heart of his play, Our Town. Set in the fictional Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, its central characters Emily and George meet as children. Despite differences in temperament, they fall in love as they mature, and marry. A few years later, Emily dies in childbirth. A remarkable thing then occurs:

She’s given the chance to revisit her life, any moment of her choosing. After picking her 12th birthday, the joy upon seeing her mother and father again is quickly swallowed up by the rush of daily living; Emily can’t get anyone to stop and really look at her. Overcome, she begs to once again be released from the world of the living: “I can’t. I can’t go on. It goes so fast. We don’t have time to look at one another. I didn’t realize. So all that was going on and we never noticed. Take me back—up the hill—to my grave.”

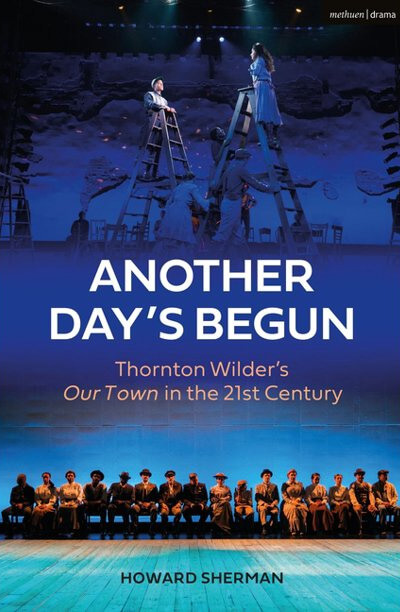

Opening on Broadway in 1938, Our Town won the Pulitzer and has been continuously staged ever since. In his fascinating new book, Another Day’s Begun: Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in the 21st Century, author Howard Sherman analyzes the play’s meaning and explores its continuing impact on audiences across the globe.

Despite its enduring popularity, Our Town carries a whiff of “sentimental, old-fashioned, golden-hued, sepia-toned, done-to-death nostalgia”—unfairly, Sherman believes. Yet this reputation clings to his book’s opening, which recounts the play’s early production history. This part will be a bit of a slog for readers with fuzzy memories of having read the play in school—or maybe even having acted in it—and especially for those unfamiliar with it. Instead of feeling intrigued, you might get impatient—but stick with it. The book really comes alive when Sherman unveils an oral history from over 100 directors and actors involved in both amateur and professional productions from 2002 to 2019, from Sing Sing to Broadway, including multiracial, deaf, and bilingual versions, to understand why and how this story about white people in a small, sleepy New England town can possibly continue to resonate in today’s world.

First of all, it’s not as Pepperidge-Farm-folksy as we might remember. “There’s just a coldness to the story that I think is hard for people,” director David Cromer points out. The play is usually set on a bare stage, with a minimum of props, and doesn’t carry a feel-good message—it carries a warning: We don’t notice or appreciate life as it’s happening. Too often, we miss each other in the moment. (This is what’s so painful to Emily that she chooses to return to the dead.)

A character called the Stage Manager narrates the play, and professional and amateur actors alike share their impressions of how playing that role caused them to engage with the play’s deeper meaning. Helen Hunt, who starred in two of Cromer’s productions, says, “[Wilder’s] not selling a religion or faith, he’s not telling you it’s all going to work out, he’s simply saying it’s an unnamable something that has something to do with human beings.”

Marielle “Théo” Lambert Scott, who played the Stage Manager in a Louisiana State University production, recalls that “I’ve seen my mom cry a handful of times. One of them was after we lost our home in Katrina…I’ve never seen her cry at a movie, or a book, or a TV show, or anything like that. She came the opening weekend and she was in the second row. I saw her. As soon as Emily slams her hands down on the table and she goes, ‘Look at me! Can’t we just look at one another?’ my mom was crying and that’s when I broke.”

For whatever ails us as a people—9/11, a suicide bomber at an Arianna Grande concert, mental illness, and incarceration are just a few examples Sherman explicitly addresses—Our Town seems to be a potent remedy. He writes, “Thornton Wilder was rather explicit in what he wanted us to take from Our Town. It is not hidden or oblique. If anything, it is a charge to each and every audience about how to think about how they approach life, to appreciate life and appreciate others while we have them.”

However alert we each are to the fact of it, life is something that happens to all of us just this way, just this once. Another Day’s Begun gives us the chance to reflect on just how singular and special that experience really is.