Review of Carpenters: The Musical Legacy, by Mike Cidoni Lennox and Chris May, with Richard Carpenter

Review by Michael Quinn

Two journalists approached musician Richard Carpenter to get his blessing on a book they were developing on the band that he’d he fronted in the 1970s and ’80s with his sister Karen (now deceased). Richard offered more than his approval. He gave his time, access to his archive, and answers to countless questions. He also took charge of the project. “Hello, and welcome to our book,” he writes on page one of Carpenters: The Musical Legacy. On the margins of every page, you can practically feel co-authors Mike Cidoni Lennox and Chris May fretting, fawning, and finally ceding control. So much for hard-hitting journalism: This is the world according to Richard.

Knowing it’s a vanity project doesn’t make it any less impressive. Gorgeously packaged, this whopper of a superfan scrapbook contains family photos, trivia, ephemera, tour schedules, interviews, and an exhaustive list of the Carpenters’ discography. It goes through their career song by song, year by year, including release dates, chart entry dates, peak positions, and the amount of time each spent on a chart.

The level of detail is fascinating and the commitment to getting it right, admirable. What the book doesn’t capture are the two things that the Carpenters are known for: Karen’s haunting voice and that incredibly distinctive sound. Those layered harmonies, arrangements, and production are all Richard’s work. As he sagely points out, “an arrangement can make or break a record.” The problem is, he never lets you forget it.

Richard’s relentless bid for recognition is understandable. History has not been kind to him. Previously, by his own admission, he had been burned by authorizing a biography he later dismissed as “the anorexia book,” as it zoomed in on Karen’s struggle with the disease which took her life at 32. Some fans continue to resent him, feeling that his workaholic tendencies pushed Karen over the edge, and that he cashed in right after her death, rushing out a bunch of unreleased (and sometimes even unfinished) material—a move he deeply regrets now. “I can hear a couple of things where I know she would really not be happy about,” he admits.

In Carpenters, Richard’s certainty about how Karen would have felt about something never wavers. Not only was he her brother and greatest collaborator; at one point, he goes so far as to call himself her “spiritual twin.” After all, he argues, they shared the same smile and the same likes and dislikes. Then again, Karen didn’t know classical music like he did, he points out, as if working to score another point in his favor. This relentless something-to-prove quality bleeds into the book and sours it. Describing an early performance, he writes, “I think I stole the show, if anybody did. I was voted outstanding instrumentalist. In addition, we were named based best combo, and the Richard Carpenter Trio took home the overall sweepstakes trophy.” (Did I mention this guy is big on one-upmanship?)

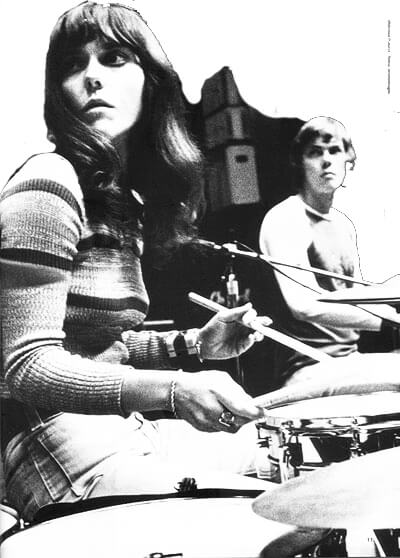

It was in an early iteration of this trio that 16-year-old Karen, on drums, secures the group’s first record contract—for her singing. The reason Herb Alpert later signed them to his label A& M Records? “Her voice,” he says. Yet Karen had to be coaxed from behind the drum kit to take center stage. “She couldn’t accept the fact that she was a world-class singer,” Alpert says.

That voice is sadly missing here. While photos and memories of Karen are dotted throughout, she gets a scant two-page eulogy—an overcorrection of “the anorexia book” that likewise lightly treads around Richard’s own demons, including an earlier addiction to Quaaludes, which he calls “my pills.”

If you’re unfamiliar with the Carpenters, this book is not the place to start. The writers don’t hold hands or wade in from the beginning. They’re not big on background or stage-setting; they plunge right in. They’re interested in the nitty-gritty, like which singles were only released in Japan, and with which artwork (which everyone admits is always really bad). The technical bits might be of interest to other musicians, but these always carry an off-putting whiff of Richard’s self-importance. The same quality that might have made him an excellent producer and arranger—namely, control-freak energy—works against the best interest of the book. The making of it seems like a mild ordeal for all involved. At one point Richard complains of being “talked out.” At another, while being grilled about some legendary piece of Carpenters’ lore, he dismisses it as only a “mystery to the few who find this kind of arcana interesting.” He’s sometimes self-deprecating, but always comes across as both wary and resentful.

Nor is Carpenters the place to find pages of poetry to ponder. It’s not like the Carpenters were great lyricists. They made their name covering other people’s songs—“(They Long to Be) Close to You,” “Ticket to Ride,” “(Groupie) Superstar”—with Richard’s lush, slowed-down arrangements haunted by Karen’s low, plaintive voice, always sounding sad, but hopeful. These feelings are mirrored in the listener: You feel like she understands what you’re going through, and no matter how bad you might be feeling, there’s also a chance that you’ll feel better. It’s a voice like eyes: It makes you feel seen.

Yet even in their heyday, the Carpenters suffered from an uncool image. They were cleancut white kids from the California suburbs singing the same songs you’d hear in an elevator. Richard still resents this. He makes a case for the albums, the choices he made in putting them together, but it’s the singles that tell the story of their career, and they still hold up. They are of their time, but with that magical timeless quality that all the greats share. What Carpenters shows is that that as much as you might favor one of the siblings, the sum is truly greater than its parts. Richard’s sunny harmonies carried the dark notes of Karen’s voice. Others have since followed this formula; no one else has done it in quite such a winning way. “Individually, we were something,” Richard says of Karen. “But together we were really something else.”

Quinn on Books: One-Sided Story

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”

2 Comments

Pingback: Quinn on Books: One-Sided Story – Nice Info

Thorough and level review/critique. However the authors are not “two journalists” … they are one journalist and one historian.