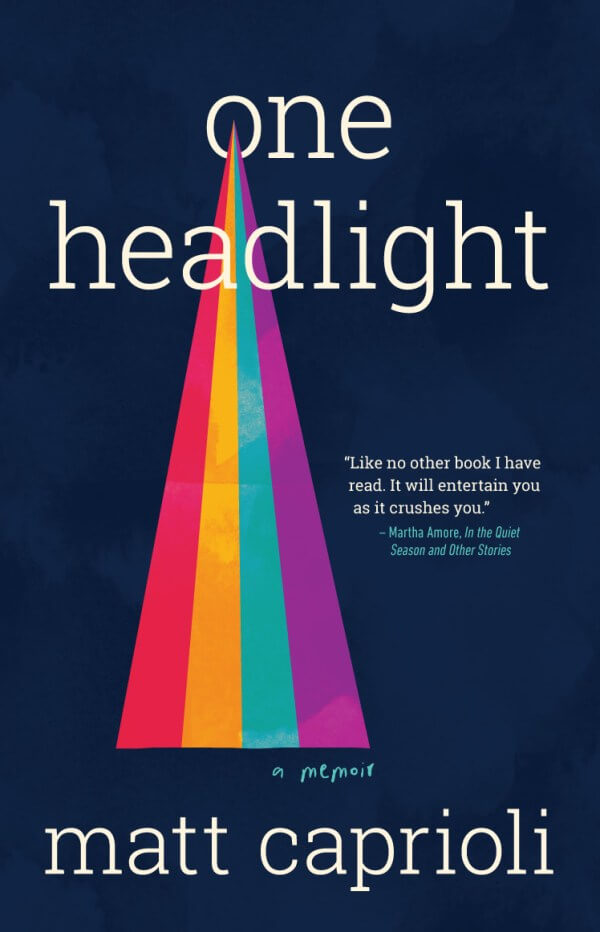

We are children for only a short time, but spend the rest of our lives making sense of our childhoods. It’s an impressionable period of so many firsts. We soak them up like a sponge. In his heartfelt coming-of-age memoir One Headlight, Matt Caprioli (a former arts editor of this paper) wrings out his origin story as a gay man and writer. It drips with regret, colored by the loss of his mother Abby, who dies at 54 of colorectal cancer right as Caprioli is coming into his own as an adult. Eternally optimistic yet almost willfully naïve, Abby is unable to provide her son with a stable upbringing, yet she gives him something far more valuable: a healthy sense of his own worth.

A near fatal car accident when Matthew is a baby causes Abby to embrace the fundamentalist faith of her childhood. As a boy, Matthew mimics the movements of the men at their church, hoping to ape their masculinity (he is fighting against his understanding that he’s gay). Then he discovers ice-skating.

From his first turn on the ice, Matthew is a natural. Abby is immediately supportive and works to get him better skates and lessons. At a tournament, Matthew excels in the first round, then buckles under pressure. His dad calls him a loser, while Abby says, “You know you’re still my champ.” Despite his natural aptitude, Matthew shies away from the sport, afraid of its gay associations, and shrinks from his mother’s kindness.

When their parents divorce, Matthew’s half-sister Lee Ann prefers to stay with their police officer father, while Matthew is drawn to Abby’s encouraging but chaotic presence. The children ping pong between culturally-barren suburban California and a poverty-stricken stretch of Alaska. “Homeschooling” Matthew means Abby lets him wander around the local mall while she’s working. She cheerfully drifts from one dead end-job to another: working at a bakery, as a dishwasher, as a maid.

One visit, Abby picks up 12-year-old Matthew at the airport during a snowstorm. She’s driving a broken-down Mustang (short one window and a headlight; she doesn’t have the money to have them repaired) which she calls Rocky (after the boxer). Exhausted after her double-shifts, she starts nodding off at the wheel. To keep her awake, Matthew turns off the heat and tells her to roll down the window. Blasted by the cold, they then blast gospel music on the radio, singing along at the top of their lungs as they barrel down an ice-slicked mountain.

Seemingly unable to make a smart decision for herself, Abby takes up with Caleb, a dim-witted man 20 years her junior (whom an exasperated Matthew describes in his journal as an “idiotic idiot”). Knowing Abby’s hungry for his approval, Matthew reluctantly gives it to her, and she beams “like a kid whose parents had suddenly changed their mind on ice cream for dinner.” Abby hangs on every kind word she hears—especially from her beloved Matthew. And he likewise blooms under her care. In high school, he plays varsity tennis and is elected to the prom court. Bursting with pride, Abby crashes the dance with her doofus husband in tow.

Some might see Abby and Matthew’s relationship in One Headlight as a kind of reverse parenting. But as Caprioli sees it, “they learned from each other.” Abby encourages his writing; when he has a job at a local paper after high school, she writes an effusive letter to the editor. As he ages, Matthew sees in her “a habit of imitating whatever I tried”: ordering the same food, reading the same books, going to college (they attend school at the same time), even moving to New York.

Caprioli mentions the writing of One Headlight within the book. He wrote it longhand. It sometimes feels like he also worked on it in chunks and didn’t completely smooth the seams when he joined everything together. Some parts (like the Mustang episode) feel polished, while others feel a little less developed. There are episodes that don’t feel like they belong in this book at all, such as his brief foray into sex work. The timeline is jumpy and seems confusing even to him. At different parts of the book, he’ll tell us things he already told us, introduce characters we already know. A sanctimonious tone creeps in whenever he airs his grievances, so that your takeaway isn’t the way Lee Ann wrongs him, for example, but his judgment of her behavior.

One Headlight works best when it focuses on Abby. She’s a complex character: likable and maddening at the same time. An interesting parallel Caprioli doesn’t really explore is how he, like Abby, is forced to work a series of exhausting, physically-demanding, low-paying jobs to support his fledgling life as a writer in New York. Unlike Abby, Caprioli complains endlessly and relies on Abby not only for sympathy, but for understanding and acceptance of his sudden unavailability when he emotionally withdraws.

One of the book’s best scenes shows Matthew, fed up with Abby’s chaos infringing on his new life in New York, getting into a cab and abandoning her on a street corner with a pile of her bags at her feet and no place to go. He fights back tears but doesn’t turn around. The abandonment is brutal—in part because you could see how he felt like he had no other choice. One Headlight well illuminates the necessary pain of separating from our mothers to become who we are—and the way we continually return to them, and to who we were, to understand who that is.