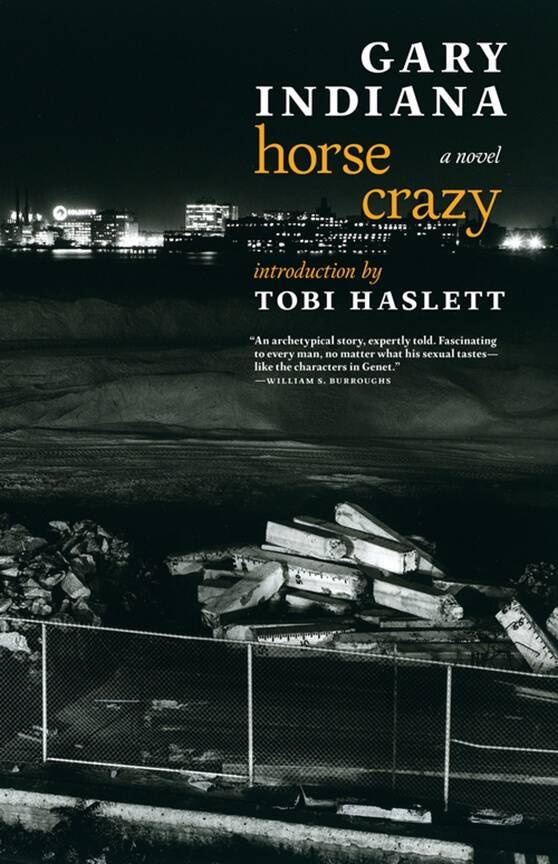

“Lost in Love”: Review of “Horse Crazy,” by Gary Indiana,

introduction by Tobi Haslett, Reviewed by Michael Quinn

Years ago, I fell for a recovering drug addict. I met him at a funeral for a man we had both been involved with. When he caught me looking, he smiled—a slow, disarming gesture that made my heart thump like a dog’s wagging tail.

He called me from rehab weekly at first, then nightly. I dropped everything whenever the phone rang. He would ramble on about his day: the unreasonable rules, the petty injustices. Late into the night, I would gently interrupt to tell him I had to go to bed. One night he told me, “You have me stuck on stupid, and that’s a good thing.” That night I couldn’t sleep, my mind racing with impossible scenarios for what a shared future might look like.

Periodically, he got a pass to leave for a day, then a weekend. Unaccustomed to freedom and with no place to go, he came to me. When I took him out for breakfast, he chewed his eggs with his mouth open while I fiddled with the napkin on my lap. When he noticed me staring at him, he winked. Our “opposites attract” relationship became a mutual source of fascination and dread.

Money changes everything

Memories of this long-ago relationship resurfaced recently after reading “Horse Crazy,” Gary Indiana’s 1989 fever dream of a novel about infatuation, need, and loneliness. The unnamed narrator, a writer and “modestly-scaled public figure,” finds his life upended when he falls under the spell of a devastatingly handsome younger man, a former junkie named Gregory Burgess.

“Horse Crazy” was Indiana’s first novel. He died last year at 74, from lung cancer. His cultural critiques, aimed at the creeping influence of capitalism on art and identity, feel just as urgent today.

The writer and cultural critic belonged to a different, more bohemian New York. His work captures a New York that was vanishing even as he wrote about it. I felt it when I first moved to the city in the 90s: a puddle of something vital that was drying up around the edges.

In “Horse Crazy,” gentrification is just starting to creep in. Apartments are gutted. The new neighbors all have briefcases. The new craze is call waiting and answering machines. Against this backdrop, the narrator struggles with his own artistic compromises, agreeing to work for a magazine whose work he doesn’t like and certainly doesn’t respect, only for the money.

He material needs are few. He’s only interested in buying books. But Gregory needs money and “emotional involvement in his need.” Gregory feels the narrator has something he doesn’t—success—but the narrator doesn’t feel successful at all. He feels like Gregory doesn’t know who he is and that he doesn’t really know Gregory, either.

Gregory spends half his time complaining and the other half fantasizing about success. He’s unreliable and frequently stands the narrator up. Even his friends see him as a lost cause. The narrator, however, is crazy about him. He sees the red flags and charges ahead anyway, like a lust-crazed bull.

The black hole of desire

“Horse Crazy” is set squarely in the era the AIDS epidemic. As the narrator’s friends get sick and die, he wants nothing more than to be taken in someone’s arms and comforted. His big fear isn’t dying. It’s that “I’m going to die before I can be truly loved.”

Gregory keeps him at a distance, insisting he doesn’t feel sexual. Yet his artwork—collages made from porn magazines—and his constant stories about strangers coming on to him suggest otherwise. When the narrator tells him that he’s desperate for some kind of affection, Gregory says, “Sure, no problem, tell me which hole you want me to put it in and how long you want me to keep it there. God knows I’ve gone through the motions enough before.” The narrator recoils, feeling like an elderly lech. Later he thinks, “The real sex of our time is fame and money, and all sex is negotiated through the porthole of those ambitions.”

Inanity and violence

Indiana’s prose is electric. “Horse Crazy” is populated by many minor characters but they all feel fleshed out—you understand and care about them. The narrator’s inner monologue which makes up the bulk of the novel is a masterclass in self-examination—and self-deception.

Indiana notices the little details that make scenes feel real as well as the larger cultural shifts, especially the way “selling out” was a losing prospect for everyone: “This culture cannot rest, until every inner life that is not for sale has been consumed by the inanity and violence around it.” Horse Crazy was written decades ago, but in its pages, you will see today’s world reflected.