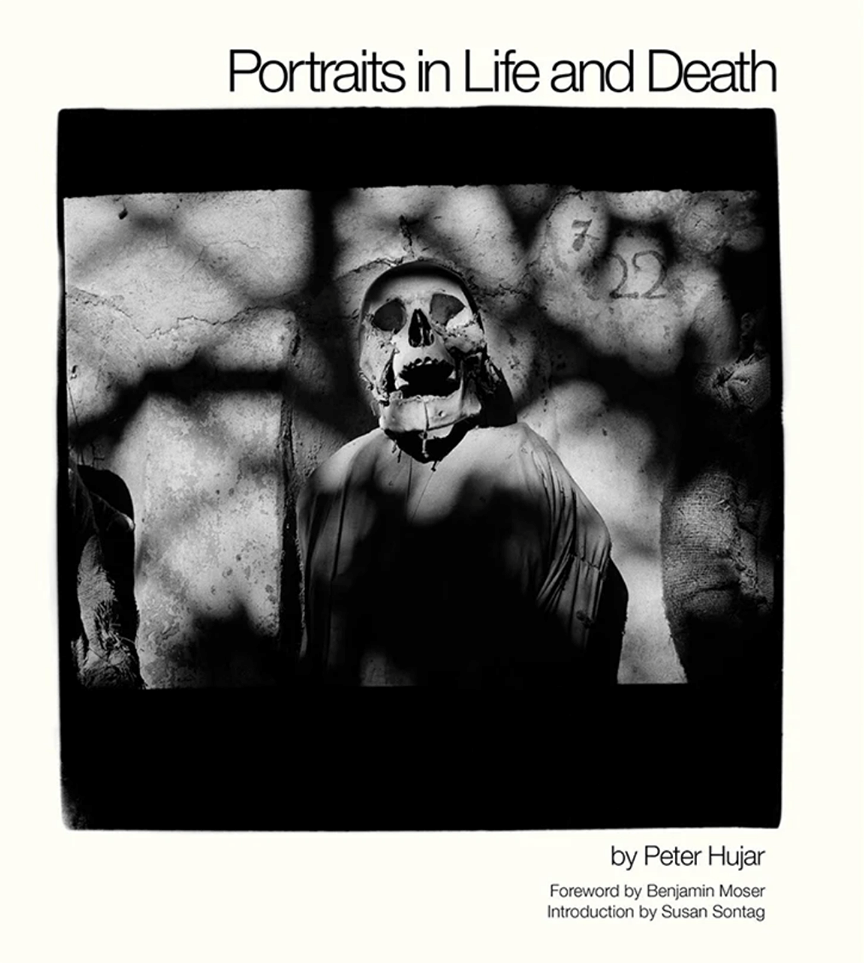

Review of “Portraits in Life and Death,” by Peter Hujar

The end of the year always feels like the end of the world to me. I feel a giddy sense of abandon: to do more, eat more, see more—and inevitably spend more. (Wheee!) January is always a shock. (Whoa.) Somehow, the beginning of the year starts in a place far removed from where December left off. It’s less like stepping off a cliff and more like tracing your finger along the smooth, rounded edge of a paperclip—a loop that brings you back to the start.

This cyclical sense of time was on my mind as I pored over Peter Hujar’s deeply compelling black-and-white photographs in “Portraits in Life and Death.” This gorgeous new edition (hardcover, with lavender end pages) is a reissue of the 1976 original, long out of print, and the only one published during the photographer’s lifetime (1934–1987).

Hujar was a contemporary of the perhaps better-known photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Both were gay men living in downtown New York who photographed many of the same people and who ultimately died of AIDS-related causes. Yet their work is strikingly different. Where Mapplethorpe’s images are edgy and provocative, Hujar’s are moodier, more mysterious. If Mapplethorpe’s focus was sex, Hujar’s was relationships—but both are rooted in intensity.

In the foreword to the new edition, the writer Benjamin Moser includes a self-portrait of Hujar leaping into the air in his loft apartment, saluting the camera. Hujar’s taut body and focused expression contrast with the playfulness of the pose, a tension of opposites the book is very much concerned with.

What the living do

The first two-thirds of “Portraits” showcase artists who prioritized personal expression over material success. For them, art was a calling, not only a career. (“A constellation of offbeat, penniless artists like the ones he gathered in this book feels sadly impossible today,” Moser laments.)

Hujar’s subjects emit a kind of utilitarian glamor. They are dressed in the clothes of the working class (button-ups, t-shirts) or nude: bare-breasted and bare-chested—both sexes have hairy armpits. They are often lying down, sometimes on the floor, sometimes on a rumpled bed or couch pushed against a cracked plaster wall, or emerging from an inky black nighttime darkness as if they just rolled over in bed to tell you about a dream they had.

Brief biographies at the back of the book provide context, but the portraits reveal who these people really are. Poet Edwin Denby sits with eyes closed, his sagging neck echoing the folds of his shirt’s lapels. Writer Susan Sontag, who penned the original book’s introduction from her hospital bed, reclines on the floor with arms folded behind her head, gazing coolly into the distance. Fran Lebowitz, cigarette in hand, sits hunched with a bemused expression so characteristic of the notoriously cranky writer.

Death becomes her

With a turn of the page, we are in another country in another century. Hujar now takes us to Palermo, Italy, where, in 1963, he photographed 19th-century mummified bodies in the catacombs. The personalities of these adorned skeletons have somehow been preserved along with the remnants of their physical bodies. Worry still etches the face of a little girl, her tiny hands emerging from huge embroidered bell-shaped sleeves as if to clasp themselves. A woman, her neck looped with a decomposing wreath of flowers that resembles a boa, seems to have turned her head to look at us pensively through her glass-sided coffin. A man’s O-shaped mouth feels like an expression of joy.

Hujar’s portraits possess piercing clarity—not just in their technical beauty but in their emotional depth. His connection to his subjects is palpable, and through his lens, we connect with them too. In their expressions, we sometimes find isolation and loneliness that echo our own. Yet, there’s also self-assuredness and glints of humor in their eyes—or the spaces where those eyes once were.

Decades after its original release, many of Hujar’s living subjects have, like him, crossed over to whatever’s next for the rest of us. His poignant dedication still applies—“I dedicate this book to everyone in it.”—and erases the categories (life, death) themselves. At its heart, “Portraits in Life and Death” is both a search for and a celebration of meaning. Let its singular vision inspire you to squeeze whatever good you can out of whatever 2025 has in store.

Author

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.