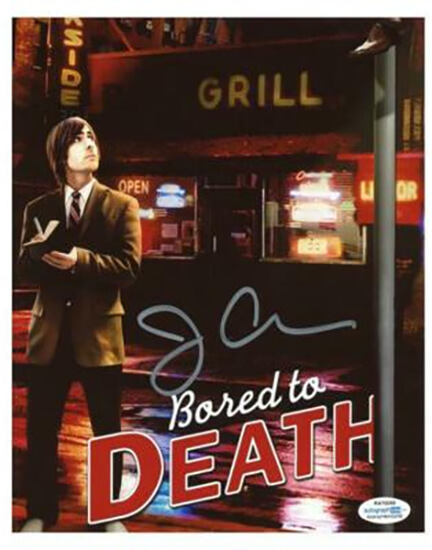

Jonathan Ames, author of several books (including You Were Never Really Here, adapted into a film starring Joaquin Phoenix), creator of two television series (Blunt Talk and Bored to Death), and sometimes boxer (fighting as “The Herring Wonder”), continues building an eclectic body of passion projects with his latest work, A Man Named Doll. This novel focuses on the improbably named Happy Doll, a fifty-something, down-on-his-luck, L.A. private eye.

Happy is also a romantic. Admiring the sound of his wooden-heeled shoes, he observes, “it’s like out of a movie, the sound effect of a man in a city late at night, alone and in danger. It’s a romantic sound.”

It’s also a noir-ish one. A Man Named Doll is an affectionate, playful tribute to the hardboiled detective genre. Set in the present day, with swarms of butterflies making sudden, unexpected appearances across L.A.’s environmentally-battered landscape, its story is narrated by Happy in short, staccato sentences (“It was rainy season. An old-fashioned one. An anomaly”), and contains all of the noir genre’s classic elements: the fiercely independent investigator; a beautiful, mysterious woman; bad guys; an urban location; a complex plot; and existential underpinnings—whatever case Happy happens to be investigating, what concerns him most deeply is the meaning of life.

At the story’s opening, Lou Shelton, an old mentor, bursts into Happy’s office. He’s in bad shape. In failing health, he’s desperate for a kidney. Would Happy consider giving him one of his? What remains unspoken is the unpaid debt between them; back when they were both cops, Lou had taken a bullet for him.

That night, working his part-time job as a security guard at an Asian massage parlor, Happy considers his obligation to his old friend. Just then, a customer goes berserk, attacks one of the women, and Happy intervenes. He spends the rest of the novel with a bandage on his face—very Jake in Chinatown.

How these plot points come together is the work of this very short novel. But I’d argue you don’t read (or watch) anything Ames for plot. You don’t even read him for voice. What Ames delivers in spades is sensibility. Like the film director Wes Anderson, Ames is a mood guy.

The self-awareness Ames instills in Happy is what distinguishes him as a narrator. He knows what his issues are, most of them stemming from feeling responsible for his mother’s death (she died in childbirth). He’s slowly working through them through years of therapy, “the only ex-cop I know in Freudian analysis.” Happy is often anxious and awkward, but he’s always self-aware. With self-knowing comes self-acceptance.

For example, Happy seems perfectly at home in his little inherited Spanish bungalow in the Hollywood Hills, which he greets by name each day. Fixing a plate of food for himself (smoked fish and marijuana gummy candies are mainstays of his diet), he observes his “odd but healthy” eating habits.

While nursing a broken heart, Happy has discovered that the real love of his life is his little rescue dog, George. “Unlike most dog owners, I don’t project onto him that’s he my child, my son. Rather, it’s a more disturbed relationship than that. I think of him as a dear friend whom I happen to live with. In that way, we’re like two old-fashioned closeted bachelors who cohabitate and don’t think the rest of the world knows we’re lovers.”

Competing with George for Happy’s undivided attention is Monica, a languid and beautiful bartender whose long hair fails to mask the scar across her face; as a child, her father pushed her through a plate-glass window. For all its romance and its nutty, neurotic sense of humor, A Man Named Doll easily and often erupts into this kind of violence. It’s only afterward that you realize how close to the surface it was all along. Happy’s go-lucky style suddenly seems less like posturing, more like a coping mechanism. He draws on the past as a way to live in the present, when “you had to be patient because time was different then. It lasted longer.”

What doesn’t last long is A Man Named Doll. You’ll zip right through it. Happily, it contains a teaser for the next volume, called The Wheel of Doll. Here’s hoping for many Happy returns.

Michael Quinn | Review of A Man Named Doll by Jonathan Ames, 2021, Little, Brown and Company, 208 pp