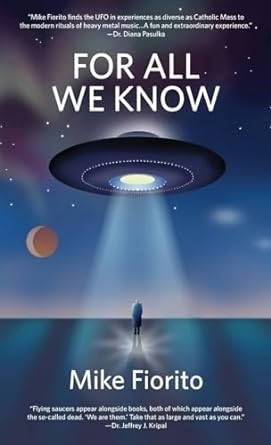

Review of “For All We Know,” by Mike Fiorito

Review by Michael Quinn

Do you believe in UFOs? For some, the existence of aliens is a given, based on statistical probability or the (limited) evidence from photos and videos. Others swear they’ve had firsthand encounters, often shrouded in mystery. Years ago, I had a boyfriend who once, with terror in his voice, recounted an eerie childhood alien abduction experience. He never mentioned it again during our five years together, possibly because of my stunned reaction.

For believers, the idea of extraterrestrial life can also evoke profound awe, akin to gazing at a magnificent sunset or a starry sky. Brooklyn author Mike Fiorito taps into this wonder in his latest novel, “For All We Know.” This thought-provoking and heartfelt coming-of-(new)-age story follows Matteo Tarquini from the 1960s to the present, charting his transformation from a kid in the projects to a philosopher of the people.

Matteo is one of three kids born to tough but loving parents who smoke, gamble and struggle to make ends meet. The family lives in a dirty Queens building with graffiti-strewn walls and the stink of the nearby Department of Sanitation. Matteo’s parents dream of a better life for their kids, but Matteo has his own ideas about what that entails—it’s not about money.

One night, a man pulls a gun on teenage Matteo to steal his radio. Matteo bolts, not because the radio is valuable, but because music is sacred to him. Shaken afterward, Matteo and his best friend, Squid, get high and blast rock records to comfort themselves. They sense but can’t yet articulate how music “can transport you. Deliver you. That music is a form of time travel.”

After a possible UFO sighting over the city, Matteo becomes fascinated with the unseen. He starts viewing his Catholic school chapel as a kind of spaceship and appreciating the “science-fiction aspects of Catholicism,” like how the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are separate entities but also the same thing.

This fascination with far-out things leads Matteo to experiment with mescaline, LSD and mushrooms, initially guided by a hippie guru named Tom Turkey and his sexy girlfriend, who reads Walt Whitman’s poetry with a lisp. These experiences expand Matteo’s consciousness, allowing him to communicate with nature. (The trees urge him to “HAVE JOY.”)

Matteo’s decision to study philosophy at New York University disappoints his family, who question its practicality. However, his true education comes from an alchemist, Pedro, who introduces Matteo to Carl Jung’s work, teaches him to meditate and pushes him beyond his comfort zone. He instructs Matteo to undress and sit naked on his lap, giggling at his hard-on. “There is something of the charlatan about him, but he is also very learned,” Matteo reflects afterward.

Matteo, influenced by the men in his life and his tough upbringing, is an astute observer and models himself on the people he admires. “When I hear someone or something that I consider worthy, I listen,” Matteo explains. Yet his interest in the otherworldly feels inborn.

Like many of us, Matteo learns to shoulder adult responsibilities like getting married, raising a kid and caring for elderly parents. And like many of us, he enjoys smoking pot, drinking beer and listening to rock music to escape those responsibilities. What sets him apart is his relentless quest for life’s meaning. He amasses a vast collection of books yet often feels that the more he reads, the less he knows. However, this search for understanding brings extraordinary dimension to his life, from strange coincidences like running into an old nun from his school days while in Lourdes to extended dream conversations with his deceased father.

After a night gambling in Atlantic City, Matteo’s elderly widowed mother, Cookie, is too pooped to move. Matteo has no choice but to carry her up to her room. Old age has diminished Cookie, but her heft strikes him once she’s in his arms: “This woman is like a mountain—stubborn and powerful, with marshy soft parts and deep dark caverns.” Fiorito nails his character portrayals in economic descriptions like this one. Cookie isn’t a shell of who she was but someone fiercely alive.

I’ve read and favorably reviewed another of Fiorito’s books for this paper, but “For All We Know” shows how much he’s grown as a writer. It feels more personal and profound, deeply informed by his life experiences. After reading it, I have so many questions I wish I had asked my boyfriend all those years ago. We’d all do well to heed the trees’ advice to Matteo: “Don’t think with your head. Think with your heart.”

One Comment

Great review, Michael. As a card carrying UFOlogist (LOL), I’ll be reading this one.