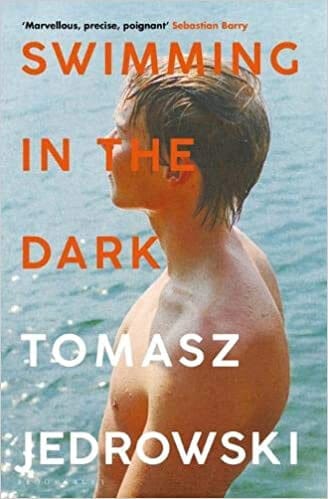

Review of Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski

James Baldwin, the late black, gay, American writer, used his work to boldly explore racial and social issues. According to Baldwin, his 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room (about an American man in Paris who falls in love with an Italian bartender) was “not so much about homosexuality, it is what happens if you are so afraid that you finally cannot love anybody.’’

The same assessment can be made of Tomasz Jedrowski’s recent novel Swimming in the Dark. Set in the 1980s, it’s a love story between two young men—an idealist and a realist—in Communist Poland.

Ludwik and Janusz both come from nothing, but that upbringing has affected them differently. They have different ideas about where they want to go in life. “‘We haven’t had the same lives. We won’t agree on this,’” Janusz warns.

A promising university graduate, Ludwik feels the stirrings of both his political and sexual awakenings. He dreads continuing his education under the Party’s filtering constraints. Even the promise of a job at the end of a long academic career holds no interest, undermined as it is by “a lifetime of lousy pay…our longing for Western comforts, our hatred for the Soviets, unmentionable or punished with dismissal.”

Street-smart Janusz doesn’t deceive himself about his limited options for the future. He sees opportunities for prestige and personal advancement by working for the government. “‘The Party cares about us,’” he later says, more as a justification for compromising his integrity than a statement of true conviction. He knows the Party’s crooked—and how to profit from that corruption.

The two men meet at a mandatory “work education camp” where they harvest vegetables for the summer. Janusz finds relief at the end of each day of hot, back-breaking work by swimming in the river. Ludwik comes across him one afternoon and the two strike up a friendship and Ludwik dares to share with him the contraband book he’s been secretly reading: Giovanni’s Room.

Of the book, Ludwik thinks, “This wasn’t distraction or entertainment: here was a book that seemed to have been written for me, which lifted me up into its realm and united me with something that seemed to have been there all along and that I seemed to be a part of. It felt as if the words and the thoughts of the narrator—despite their agony, despite their pain—healed some of my agony and my pain, simply by existing.”

In Jedrowski’s novel, Baldwin’s book is a baton secretly passed between gay men. Ludwik first catches wind of it when his best friend Karolina, realizing something about him that he’s not quite ready to face about himself, gently steers him to a gay bar and he hears some older queens sniping about it. Once he tracks down an underground copy, it becomes a kind of compass for living an authentic life.

Ludwik has a relationship with the book before he has a seriously intimate relationship with another man. He reflects that “the more I read, the more scared I became: the immensity of the truth and the lies I’d been telling myself all those years lay before me, mirrored in the narrator’s life as if someone were pointing a finger at me, black on white, my shame illuminated by a cold, clear light.”

Janusz, while not so ideologically stirred by what he reads, gets the message that Ludwik’s possession of the book carries: he’s “that way.” Their work at the camp completed, Janusz invites Ludwik on a spontaneous camping trip. They hitchhike and discover a kind of secluded Eden, “a large, brilliant lake” where they embrace for the first time, make love and tumble out their philosophies of life. For several weeks they inhabit a kind of paradise. It’s when they’re set to return to opposite sides of their shared city (Warsaw) that their relationship will be tested. Janusz warns, “‘We’ve always been a secret, Ludwik. It’s just that until now there was no one to hide from.’”

Swimming in the Dark is a sensitive, realistic portrayal of a real connection and a doomed romance, expertly capturing the strange, singular, inchoate feelings of the dawning of same-sex desire, which is so much deeper than sex, although sex is part of it. Undressing after getting unexpectedly caught in the rain, a young Ludwik sees best friend Beniek naked for the first time and feels “something tingling inside me like soft pain.” Yet the earlier, foundational feeling is something else. As a child, all Ludwik understands of his feelings toward his best friend is, “I wanted him to be like my brother, to be around me always.”

As Baldwin well understood, a gay man views the world through the eyes of “the other.” Thinking about what would interest him for his dissertation, Ludwik is again drawn to Baldwin’s work. His stories “dealt mostly with the black man in American society, of his discrimination and shunning. I could see its relevance, could see how it exposed the double standards of the West, how it showed racism and white supremacy behind the liberalism and democracy extolled by the capitalist powers. At the same time, of course, I could identify. I carried my difference, my shame, on the inside. It wasn’t visible…but it was there, and it was a danger.”

Author Jedrowski understands the debt gay men owe writers like Baldwin for being unafraid to express the truth about themselves in their work. It shines a light to show others the way forward. With this powerful novel, Jedrowski proudly carries the torch. – Michael Quinn