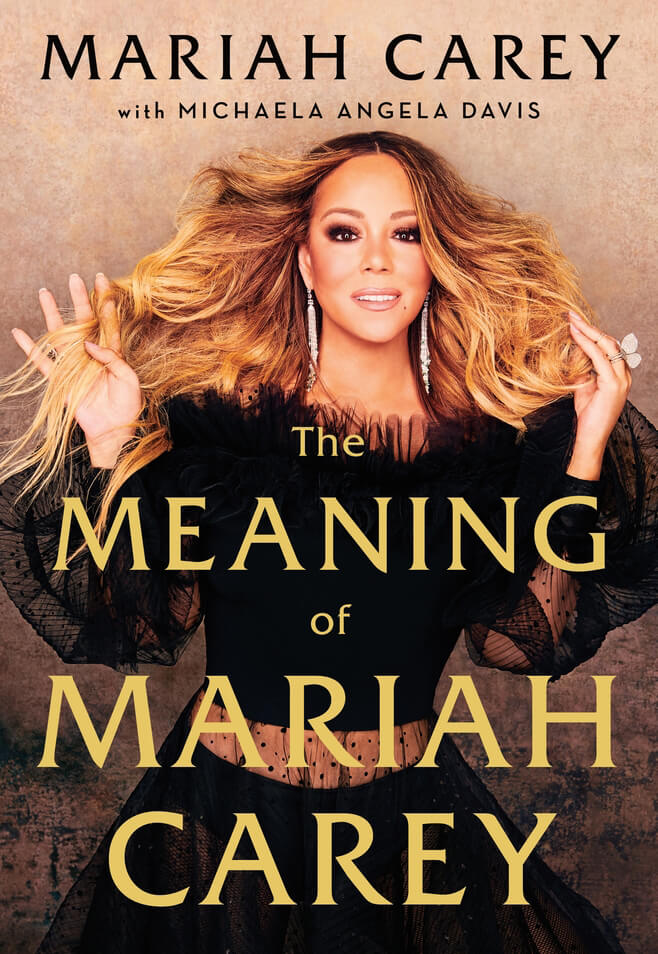

Review of The Meaning of Mariah Carey by Mariah Carey with Michaela Angela Davis

Review by Michael Quinn

The misleading title of Mariah Carey’s new memoir, The Meaning of Mariah Carey (written with Michaela Angela Davis), suggests an interpretation of the singer-songwriter’s public persona. After all, Carey’s had nineteen number-one hits—more than any other solo artist in history. What does it mean to be a household name?

That’s a question never really addressed, let alone answered. One gets the feeling Davis has plugged Carey’s anecdotes into a standard rags-to-riches format. As with her music, Carey is fond of riffing, and you can feel the work Davis does here to wrangle these odd bits into a cohesive narrative. Over 350 pages are divided into four parts: childhood, stardom, a major low point, and finding God. It bulges in places and is patch-bare in others. It hops around chronologically. Many points are emphasized, unfortunately, by adding the word “dahling.” Yet, like Carey herself, the story is always fascinating.

The daughter of a Midwestern, Juilliard-trained, white mother and a Bronx-born, military-strict, Black father, Carey’s sister (a drug-addicted teen mother) and brother (violent and unpredictable) are “both older and darker,” raised to address their parents as “Mother” and “Father” as if “the formality might elevate [the family’s mixed race] status to respectable.”

Carey’s parents split when she’s four. She experiences them separately. Their races confine them to two different worlds. So do their personalities: her mother’s bohemian slovenliness, her father’s austere discipline (he gives “little Mariah” a single Ritz cracker to quell her appetite before dinner). Growing up in Suffolk County, Long Island, Carey “passes” as white, but feels like neither side of the family can truly embrace her as their own.

Drawing a family portrait at school, she’s teased by the adults in the room for having “used the wrong crayon” to color in her father’s skin. Another time, an elementary school friend, meeting Carey’s father for the first time, assumes he’ll be white. She bursts into tears when this Black man opens the door.

Carey’s “matted, tangled mess” of hair is another badge of her otherness. She recalls, with a kind of wonder, the way a friend of her brother’s wordlessly, patiently picked out the knots on a drive to the beach when she was a little girl. (As if to commemorate the sacredness of this experience, a photo from this day is used on the book’s back cover.)

The family’s in-fighting is the only constant in Carey’s young life. She learns to self-soothe: “When I sang to myself, in a whispery tone, it calmed me down.” Her father doesn’t encourage her budding musicality, for a reason that doesn’t seem to cross her mind: perhaps he doesn’t want Carey to turn out like her mother.

Carey’s mother isn’t nurturing, but she’s the reason there’s music in the house. Carey recalls that “jamming with jazz musicians was close to a spiritual experience. There’s a creative energy that flows through the room. You learn to sit and listen to what the other musicians are doing, and you get inspired by a guitar riff or what the pianist is playing. When you are in a zone, it is a miraculous madness.”

It’s almost jolting to be reminded that, at her core, underneath the tight dresses, flashy jewelry, and windswept hair extensions, this is what Carey is: a musician. Musing about her lifelong Marilyn Monroe obsession (Carey relates to both Monroe’s unstable childhood and star transformation), she proudly boasts of owning Monroe’s white piano: “it’s a treasure and my most expensive piece of art.” Yet it’s a throwaway observation—“Pianos are elegant, mystical, and comforting”—that reminds you that Carey actually knows her way around this instrument.

“I think if you are a woman, with an incredible voice, your musicianship gets underplayed,” Carey reflects at one point, discussing Aretha Franklin’s influence. That Carey believes this devaluation applies to her own craft is obvious. So it’s a puzzle while she doesn’t delve into the subject more deeply here. There’s scant mention of early influences, for example. Carey writes, “Stevie Wonder is my diamond standard,” but doesn’t unpack the reasons why.

Carey’s own lyrics are quoted throughout the memoir, sometimes establishing a one-to-one relationship between song and the personal experience that inspired it. More surprising is her candidness about the merits of some of her songs, including one of her biggest hits, “Hero.” Written for a film, intended to be sung by Gloria Estefan, Carey calls it “fairly generic” and “a bit schmaltzy.”

Carey is equally blunt about her drive. “My career as an artist was the most important thing to me—it was the only thing,” she writes. From childhood, her “only goal” is to score a record deal: “It was as if I was holding my breath until I could hold a physical thing, an album that had ‘Mariah Carey’ printed on it.”

Carey books work as a backup singer while still in high school (also completing 500 hours of beauty school). She moves to the City, lives on a dollar a day (a budget often blown on an obsession with H&H bagels), works coat check in a sports bar, and pounds the pavement in a pair of her mother’s old black ankle boots, “a size and a half too small.”

Signing a shady producer’s crappy contract is worth it for one reason: Carey now has “The Demo,” the first compilation of all of her early musical ideas.

Other female backup vocalists, who take pity on Carey’s grumbling stomach and shabby clothes, take her under their wings and bring her to industry parties. At nineteen, in a borrowed black dress, black tights, slouchy socks, and Vans, she’s introduced to Sony record producer Tommy Mottola, “a potent combination of father figure, Svengali, business partner, confidant, and companion. There was never really a strong sexual or physical attraction there, but at the time, I needed safety and stability.”

Carey spends a long time justifying this decision that will imprison her in a relationship for the next eight years. She’s determined as ever to succeed—“I became his new star just as he was beginning a huge position at a new label, so he had the influence to clear the runway for my ascension into the sky”—but her age and naiveté poignantly reveal themselves. “At the first real wedding I ever attended I was the bride,” she writes.

In Carey’s account, Mottola is a control freak. Carey’s kept out of most of the pivotal meetings concerning her career, even as label executives refer to her as “The Franchise.”

Mottola whisks Carey away from her support network in the City to upstate New York, to his house in Hillsdale (which she calls “Hillsjail”). Determined to enjoy her breakout success, Carey builds her own dream mansion (not far from Sing Sing), which she realizes, as soon as construction’s done, is a different kind of prison, with Mottola as her warden.

Through the support of couple’s therapy, Carey begins venturing out on her own. She meets Derek Jeter at a fashion crowd dinner he crashes. It’s as if Jeter’s stepped out of one of her love songs (the Joe DiMaggio to her Monroe). Their romance is giddy and touchingly innocent. For Carey, “the intimacy of our shared racial experience was major.”

Striking out on her own—divorcing Mottola and, in a sense, her label—Carey’s career is upended with the release of the film Glitter. Meant to be a star-making vehicle, the quasi-autobiographical story (about a mixed race singer determined to be a 1980’s

superstar) is slammed by critics, and opens on the same day as the attacks on the World Trade Center.

The first single debuts at No.2—a failure for a star of Carey’s stature. “Like a stand-up comic who bombed a set,” her guerilla publicity stunt—appearing on MTV’s Total Request Live (TRL) pushing a popsicle cart and doing an impromptu striptease—makes her the laughing stock of a nation. Sleep deprived, emotionally exhausted, she’s soon institutionalized.

“I did not ‘have a breakdown,” Carey insists. “I was broken down—by the very people who were supposed to keep me whole.” Carey blames her mother and brother, who sided with the label’s demands over Carey’s well-being. They see her as “an ATM…with a wig on,” she believes.

Religion proves to be a stabilizing force in Carey’s life, followed by a marriage to Nick Cannon, and motherhood. At a recording session while Carey’s pregnant with twins, Tony Bennett quips, “I never sang with a trio before.”

In The Meaning of Mariah Carey, Carey gives herself the same kind of happy ending you’d expect from romance novels and fairy tales. I don’t think this means her career is over. It’s just hard to see how it will continue to evolve. Carey’s hit on the winning formula—if not for innovation, at least for stability. “Being Mariah Carey is a job—my job,” she snaps. The meaning of that couldn’t be clearer.