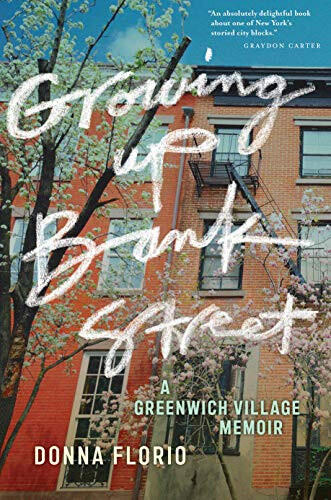

Born in 1955, Donna Florio lives in the same “barbell”-shaped West Village apartment she grew up in. Her new book, Growing Up Bank Street, recounts her bohemian childhood and coming of age, as well as the history of the neighborhood, stories from some of its longtime residents, and notable celebrity encounters, including John Lennon (whom she sprinkled while watering her flowers), social activist Bella Abzug (with whom Florio’s father tussled), and the “stork tall and emaciated” punk rock musician Sid Vicious, newly sober and just out of jail after the murder of longtime girlfriend Nancy Spungen.

During Florio’s girlhood, Greenwich Village was a mix of “painters, social activists, writers, longshoremen, actors, postmen, musicians, trust-fund bohemians, and office workers. Some were born here; others came because our street let them live and think as they liked,” Florio writes.

That latter group included Florio’s parents, Anne and Larry, opera buffs who fall in love on the “cheap seats” tickets line at the Metropolitan Opera. Marriage and little Donna arrive in short order, and the young couple discovers that “bohemia and a squalling baby were a bad mix.” They give up their room for the crib and sleep in the living room on a pullout couch.

While Anne continues to pursue her singing dreams on the stage of the nearby Amato Opera, Larry’s forced to find more traditional employment in order to support his new wife and daughter, who, at age four, makes her own stage debut in Madame Butterfly. Mother and daughter then join the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera: more prestigious, but a lot less fun, especially when Donna’s repeatedly told by her father, “‘You ruined my life by begin born!’”

Kind-hearted neighbors, another pair of opera singers with a young daughter, provide refuge for Donna from her parents’ fighting. The building’s extended family includes an eccentric old actor who roams the hallways naked, working on crossword puzzles; a vaudeville dancer; and an alcoholic hoarder. Marion Tanner, “the real-life aunt of the author Patrick Dennis, who wrote the best-selling novel Auntie Mame, which would spawn a Broadway play, a Hollywood movie, and a Broadway musical,” lives down the street and acts an impromptu babysitter, housing many of the neighborhood’s unwanted misfits. “Strange, I knew, was not always dangerous,” Florio writes, having been hardened by encounters with the street’s perverts, criminals, and eccentrics. “‘We weren’t brought up in the Village. We were yanked up,’” a childhood friend points out.

Growing Up Bank Street is most compelling when it focuses on the specifics of Florio’s childhood, as well as her adult relationships with some of the building’s longtime residents, such as her older neighbor Al, who over forty years “became increasingly like an uncle who lived next door…We knocked on each other’s doors to borrow brandy, negotiate vacation mail pick-ups, or figure out a new gadget together.”

Less successful are the oral biographies Florio shares, having “used my leverage as a native of Bank Street to coax stories from my neighbors: whom they’d loved, where they worked, whether they’d fulfilled their dreams.” Plunked down as they are, and disconnected from Florio’s personal narrative, they feel like filler, perhaps to account for the many years when Florio lived elsewhere, whether in Boston for college or the many years she later spent overseas.

John Kemmerer, “my elusive neighbor, the gray-haired loner in the hall,” is made central. Florio shares excerpts from his journals, praising his gifts as a writer as a way to air out her own lifelong insecurities in that arena. For the reader, it’s a bit like arriving hungry after being invited for dinner, and having your hostess explain, while setting the table, that she isn’t much of a cook.

Unfortunately, that inexperience as a writer sometimes shows through. Rather than follow a straightforward chronology, Florio’s chosen to arrange her material by theme. Time periods and their associated memories tend to repeat themselves to diminishing effect. The book starts off strong, then sputters and meanders. Florio’s obviously done her research about the neighborhood’s history, but trying to encompass so much was likely overwhelming. “This building of mine, I came to realize, this 63 Bank Street, holds the stories of America,” she writes. It’s like she realized she was sitting on a goldmine, but shortchanged herself.

I wish Florio would’ve trusted the power of her own story to stand central, rather than squeeze it to its margins. We see her as a child, a teenager, and as a woman, but we don’t witness the transitions. These crucial changes all happen off the page. Likewise, multiple marriages are referred to only in passing. It would’ve been interesting for Florio to reflect on a romantic relationship within the same walls that her parents’ unfolded. Her perspective on their relationship likely changed as she aged, but we only see it through a child’s eyes. A kind of willful naiveté reigns supreme. Much of the book’s material is viewed through rose-colored glasses.

Florio was a girlhood friend of Mary Jacobs, whose mother, Jane, wrote the seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which made (according to Florio) “compelling arguments for the vibrancy and social cohesion of communities with a wide mix of classes and ethnicities, along with small shops and residential buildings that encourage neighbors to form ties with one another.” Evidencing the unique kinds of lives that cities can foster, Florio’s heartfelt work is like a valentine marking a place in that book’s pages, dedicated to a way of life that’s largely vanished, even as it’s still being lived.

Quinn on Books: 325 Square Feet of America

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”