In October, at PS 676, English Language Arts teacher Jen Thomas led her fifth-grade class across the Hamilton Avenue Footbridge, which spans the Gowanus Expressway between Red Hook and Carroll Gardens. Directly on the other side, the students got to take a look at Brooklyn Collaborative, a school for grades six through 12 that some of them may attend next year. The journey was only 0.3 miles, but the kids didn’t like what they saw along the way.

The pedestrian overpass – which dangles above four lanes of local traffic, five lanes of cars entering or exiting the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, two off-ramps, and an on-ramp, while also weaving below five lanes of I-278 as it bends into the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway – was in bad shape.

“They basically said it was scary and dangerous,” Thomas recalled. “They said, ‘We don’t like this bridge. We don’t want to walk across it. We don’t feel safe.’ I said, ‘What can we do about it?’” The students ended up using their lunch period to collaborate on a letter addressed to Governor Andrew Cuomo and their state assemblyman, Assistant Speaker Félix Ortiz.

The kids wrote that the bridge contained “A LOT of trash, like dangerous glass, plastic, empty bottles, dog poop, and even old tires. We noticed that it smelled like rotten eggs.” They also spotted gaps in the concrete safety barrier on either side of the bridge. They declared the disheveled structure “ugly to look at” and “very bad for the environment.”

To improve the bridge, they asked for minor structural repairs, a major cleanup, and the installation of public trash cans. “A nice entrance with clear signs and directions would help people know where to go,” they noted, while also speculating that “a clear, plexiglass dome cover” could make the bridge less hazardous during rain or snow.

It didn’t take long for Ortiz to show up in Red Hook with New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) Brooklyn Borough Commissioner Keith Bray. With Thomas’s class, Ortiz and Bray walked across the bridge to examine its problems.

It didn’t take long for Ortiz to show up in Red Hook with New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) Brooklyn Borough Commissioner Keith Bray. With Thomas’s class, Ortiz and Bray walked across the bridge to examine its problems.

“I saw a lot of graffiti and holes the size of a baby! The bridge also shook a lot,” fifth-grader Jing Yu Chen recounted.

“If it were fixed, kids could walk across the bridge and feel safe,” Hannah Espinosa added.

The NYCDOT communicated the students’ concerns to the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), which owns the Hamilton Avenue Footbridge. On November 20, Ortiz brought state officials for another PS 676 field trip, giving the NYSDOT a firsthand look at the problem.

This time, local civic leaders John McGettrick and Robert Berrios joined the students for the walk. “This is what engagement and advocacy are all about,” Ortiz commented.

As they crossed the Gowanus Expressway, the kids and adults discussed ideas. Could the brick wall facing Hamilton Avenue on the west side of the bridge become a mural, introducing Carroll Gardens residents to the culture of Red Hook? Could the New York City Department of Environmental Preservation’s fenced-off, overgrown lot at the northeast corner of Hicks and Nelson streets someday turn into a park? What about the underutilized expanse of sidewalk at the other end of the bridge? And could the NYSDOT reposition the bridge’s entrance so that pedestrians wouldn’t have to walk along busy Hamilton Avenue to use it?

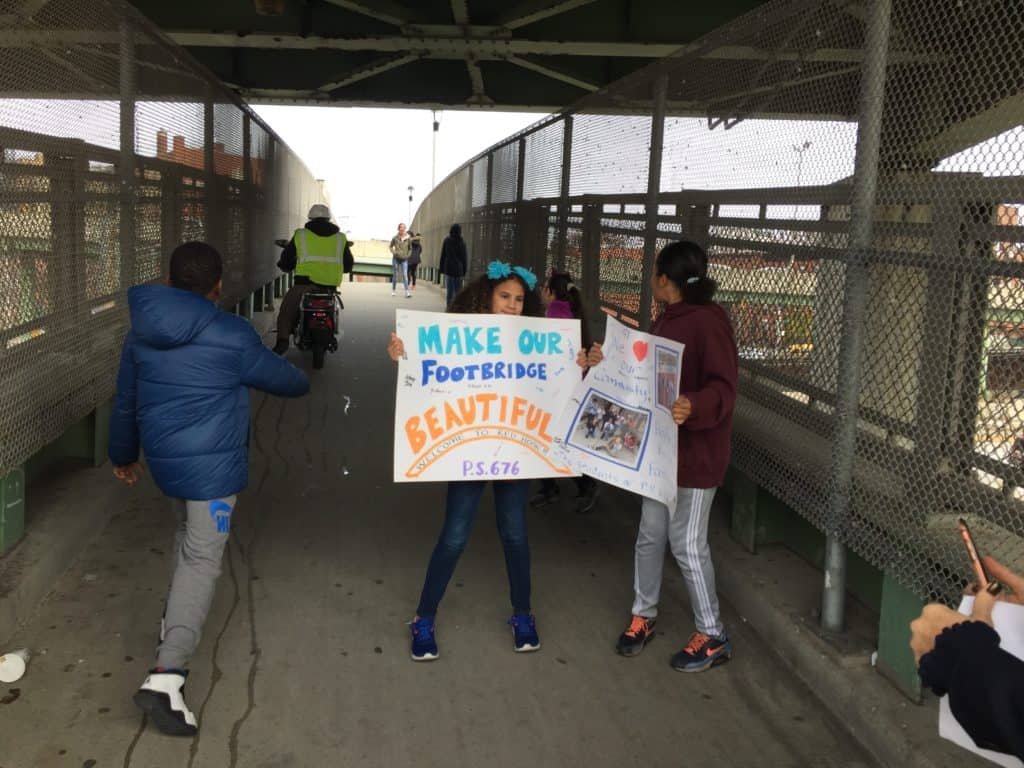

At the bridge’s midpoint, kids – some of them holding handmade signs (“MAKE OUR FOOTBRIDGE BEAUTIFUL”) – jumped up and down and felt the overpass wobble. Did this hint at structural unsoundness, or were bridges allowed to shake a little? (In 2011, the Hamilton Avenue Footbridge closed for four months as an emergency measure, at which time the NYSDOT added 9,000 pounds of steel reinforcements and replaced much of the concrete.)

Over the course of the journey, many cyclists – several of them on fast-moving electric bikes – made their way across the bridge, steering around the pedestrians until the students and their chaperons asked them to dismount. Again, multiple solutions came to mind: a separate, well-marked bike lane if there was enough room for it, or signs instructing cyclists to walk their bikes if not.

“We’re just here today listening and observing, but we’ll be getting back to the Assemblyman sooner rather than later,” said George Palermos of the NYSDOT. “Definitely there’s room for improvement, and that’s why we’re here.”

Surrounded by water on three sides, Red Hook has few points of entry and exit. The importance of the Hamilton Avenue Footbridge – including, even, its cosmetic state – reflects the tenuous connectivity between Brooklyn’s largest NYCHA complex on one end and the brownstones of Carroll Gardens on the other. With a nicer pedestrian overpass, “maybe people on the other side would even want to come visit our neighborhood or attend our school,” according to PS 676’s letter.

In October, the Department of Education announced that – in order to solicit additional community input – it would delay a proposed rezoning of seven elementary schools in District 15, which encompasses Red Hook. Advocates for PS 676 had protested a plan that, in an effort to relieve overcrowding in certain schools, would have shifted some of District 15’s internal boundaries but would have declined to expand the catchment area for PS 676, which occupies the area’s most underutilized campus.

94 percent of the students at PS 676 are black or Latino. As a means to reduce segregation, administrators at PS 676 would like to see schoolchildren from Carroll Gardens commute across the footbridge, and they believe that the local built environment will play a role – depending on the message it sends – in facilitating or foreclosing an integrated future for their school. Echoing her students, principal Priscilla Figueroa underlined the significance of the bridge as a matter of “diversity and equity.”

The decision on the District 15 rezoning will now take place in 2020. In the meantime, PS 676 hopes to show the public – and any skeptical parents – all it can do for its pupils. Upgraded science and technology programming has joined a new emphasis on neighborhood involvement and activism. PS 676’s classroom-without-walls includes the Columbia Street Farm and the Mary A. Whalen, the historic oil tanker at Atlantic Basin. In September, the school supervised the NYCDOT’s installation of a blacktop mural intended to increase street safety at the intersection of Nelson and Columbia, and in the same month, students marched in the Climate Strike at Coffey Park.

“For me, education is way more than just ‘Are they meeting the standards?’ – although that’s a big part of it too,” Thomas said. “We’re really trying to work in the community and get the kids plugged in.”

PS 676’s Hamilton Avenue Footbridge project hasn’t ended yet. Once the kids have determined exactly how their ideal bridge would look, they’ll create a three-dimensional model to showcase their vision.

“We have to do a blueprint first,” Figueroa explained. “We’ll look at it, talk about it, do some research, gather some stats, and then get into the STEAM lab to actually create a model. That’s part of the process. This is the very beginning. This is them saying, ‘There is a problem.’ This could be a yearlong project.”

One Comment

So proud of these Students at P.S. 676