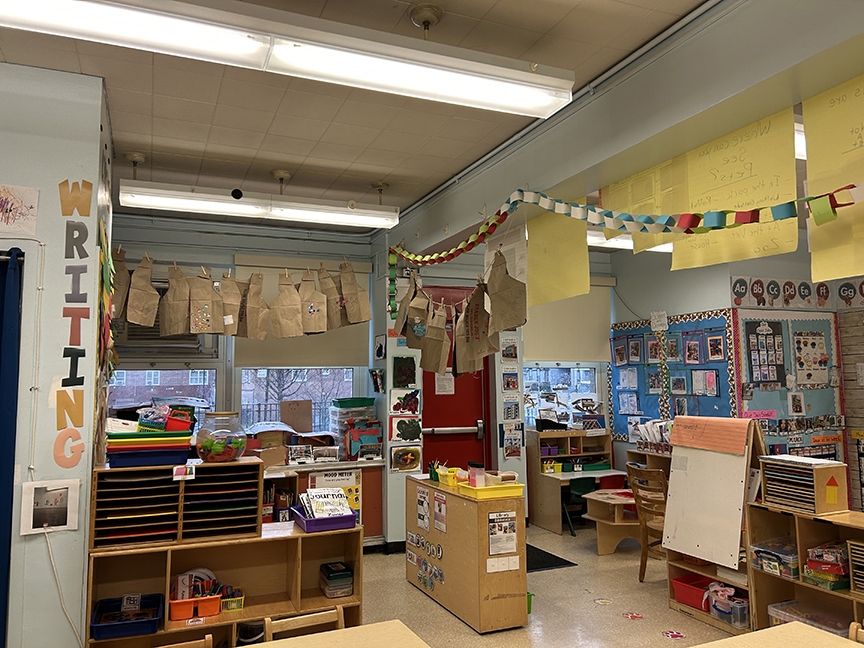

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would.

P.S. 15’s ACES program – standing for Academics, Career, and Essential Skills – focuses on students with intellectual disabilities and/or neurodivergent students. In ACES classrooms, students are provided with support based on their Individualized Education Plan. Commonly referred to as an IEP, these plans ensure students with disabilities have the resources they need to thrive in school. They include partnerships with teaching assistants and student aides known as paraprofessionals, or “paras” for short.

But P.S. 15 makes sure every one of its students – regardless of personal needs – feels at home and included. ACES students arrive at and leave school at the same time as their peers, eat lunch together, and participate in the school’s plays. Many ACES classrooms are integrated as well, consisting of students with and without IEPs.

“Everything that a general education student needs to have, students with intellectual disabilities will also be afforded the same thing,” says P.S. 15’s Parent Coordinator, Melissa Johnson. The ACES program was established at P.S. 15 in 2008 and was designed to provide students with extra needs a more inclusive public school experience, “as opposed to having to be segregated into a different school,” says principal Julie Cavanagh. These programs haven’t just helped students, Cavanagh explains; they’ve “really had an impact on the staff and the community’s understanding of neurodiversity and true inclusion and integration.”

“The kids are just so accepting and flexible and loving with each other,” she adds, “which I think certainly is what happens when diversity is embraced and valued and centered.”

A school is about access

“We live in a society that is very othering for a lot of reasons and in a lot of circumstances. And certainly, there’s a lot of lack of understanding of how to be truly inclusive and integrated” regarding neurodiverse children, Cavanagh explains. “Our job as humans, but certainly as a school, should be about access. Everyone who wants to – or in the case of school, needs to and deserves to – has an access point.”

By “access point,” Cavanagh is referring to ways P.S. 15 meets each student at their level and engages them from there. As Johnson explains, “We have kids with Down syndrome who are in band. We have kids with Down syndrome who are in drama. There’s no limitation,” adding,

“Whatever your access point is, we are then going to find a way to make sure – if this is something you’re interested, in or you want to do, or you need to learn because it’s the standards – we’re going to make sure that it’s accessible.”

The ACES program “helps to develop and strengthen the agency of the neurotypical kids as well,” Cavanagh says, “because they can see themselves in all these different ways is positionality to kids who might have some differences than them – whether that’s a helper, whether that’s being more patient, whether that’s seeing themselves as a leader.” One of the things that makes P.S. 15’s programs special is their focus on Integrated Co-Teaching (ICT).

Every student, regardless of involvement in specialized programs, is part of ICT. This means neurotypical students are involved with their neurodivergent peers in the classroom and outside it in programs like Cookshop Culture, where they grow fruits and veggies for snacks.

Language learning

P.S. 15 also provides a Spanish Dual Language program, which began in 2010. Any child – regardless of language spoken at home or IEP plan – can qualify, and classrooms are made up of about 50% native English and 50% native Spanish speaking students. Dual Language students spend half their school day learning in English and the other half in Spanish, which means they learn the same information once in each language. This is one of the aspects of the program that contributes to P.S. 15’s goal of having every Dual Language student bilingual by the end of fifth grade. Another is the integration of every student – regardless of native language – in school programs like the annual musical.

“Dual language has historically been about learning English to assimilate,” Cavanagh says. “And of course, we want everyone to be proficient in English. But we also want students to be proficient in Spanish for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is honoring culture and ethnicity.”

“Dual language has historically been about learning English to assimilate,” Cavanagh says. “And of course, we want everyone to be proficient in English. But we also want students to be proficient in Spanish for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is honoring culture and ethnicity.”

For native English speakers, the program is incredibly beneficial as well. “Even if a child’s parents speak English, it’s still so important if your grandparents spoke Spanish or historically your family comes from a Spanish speaking family – giving students access to the language of their heritage, to the language of their culture,” Cavanagh says. The program also empowers students without an ethnic connection to Spanish, allowing them to connect to their peers across language barriers.

“In this school, we really teach our children how to advocate for things that they want or they want to see changed,” Johnson says. As Cavanagh believes, being bilingual is a superpower; “another way that reinforces our interconnectedness to each other while also holding true to our values around liberation and equity and joy.” For P.S. 15’s students, she says, the ACES and Dual Language programs are “really nice because they feel included – and they are included.”

One Comment

Thanks for making this topic so approachable.