The Gowanus Canal, separating Park Slope from Carroll Gardens, is one of the most polluted waterways in the United States. Over a century of heavy industrial use has left it with a highly toxic combination of coal tar as well as raw sewage deposits. It was added to the EPA’s Superfund list in 2010, which mandated the Federal Government to oversee its cleanup.

The EPA is wedded to a strict cleanup schedule, as detailed in its Record of Decision (ROD) which mapped out the cleanup plans. The ROD was issued in September 2013. The project will include a dredging of the canal, followed by capping the floor of the canal with a layer. The layer will prevent coal tars and other toxins that remain under the dredged bottom from creeping upwards into the canal.

The cleanup is paid for by past polluters that still maintain a corporate presence today – a group of more than thirty entities. The largest of these is National Grid, the successor of Brooklyn Union Gas, who created much of the coal tar pollution as part of its methane gas manufacturing operation. The other major polluter is the City of New York.

The bulk of the city’s pollution responsibility comes from shortcomings of the sewage system in communities surrounding the canal, including Carroll Gardens and Park Slope. Over the years and continuing through today, raw sewage is pumped into the canal during heavy rainstorms.

The ROD mandated a reduction of this Combined Sewage Overflow (CSO) which would be alleviated by the construction of two large retention tanks. The tanks would store the excess rainwater/sewage until the storm subsides. The sewer pipes would then be able to handle the quantity of water/waste, and pump everything to the sewage treatment plants.

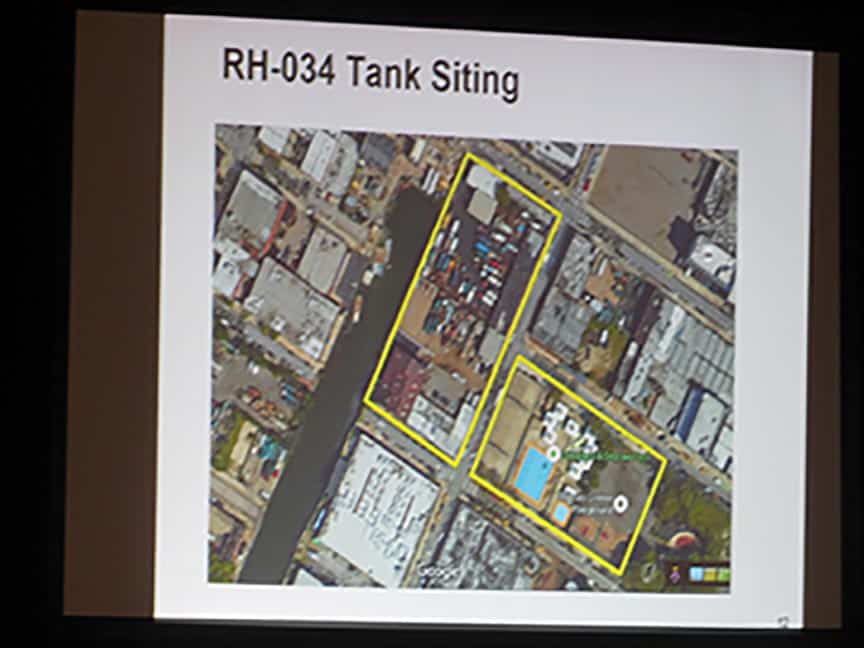

The EPA suggested placement of one tank at the Salt Lot, a facility owned by the city on Second Avenue and Fifth Street, adjacent to the Canal. The second tank was suggested for underneath the swimming pool in Thomas Greene Park, located between Douglass and DeGraw Streets.

Thomas Greene Park is the site of a former gas manufacturing plant. The EPA determined that a large pool of the toxic coal tar is located directly under the park’s outdoor swimming pool. Gravity causes the tar to slowly creep into the canal; the EPA ordered the pool dug up for the tar to be removed. They reasoned that since the pool had to be dug up anyway, the tank should be built in the fresh hole, and the pool be rebuilt above it.

Understanding the value of the pool to neighboring residents, including tenants at the nearby Gowanus and Wyckoff Gardens NYCHA communities, they also dictated that a temporary replacement pool be located nearby during the five years that the park would be closed.

The city disagreed with this plan, taking the position that the park needed to be reopened as soon as possible. Their counter proposal was to purchase the properties across the street from the park – using eminent domain if necessary – and locate the tank there.

The two real estate parcels are referred to as the “Head-of-Canal” location. Six months of intense negotations between the EPA and the City ensued, and a settlement was finally reached on April 16. This agreement allowed the city to locate the tank in the Head-of-Canal, subject to certain stipulations.

The proposed settlement is currently under public review – anyone is allowed to comment on the agreement, and those comments will be considered before the EPA finalizes the agreement. The public commentary period ends on May 31. Comments can be mailed to Walter Mugdan, U.S. EPA Superfund Director, 290 Broadway, Floor 19, New York, NY 10007, or emailed to mugdan.walter@epa.gov.

Mugdan presented the agreement on two successive days during the last week of April. He appeared at a public meeting on Monday, April 25 at PS 32 in Gowanus, and the next evening at the regularly scheduled meeting of the Gowanus Community Advisory Group (CAG) at St. Mary’s Star of the Sea home in Carroll Gardens.

At each meeting, he was subject to a barrage of questions, many of them dealing with a potential delay in the cleanup that the proposal may cause. Others questioned the additional expense to the city as they will have to purchase the properties and to dig a second hole. Thomas Greene Park is owned by the city – locating the tank there would not necessitate a land purchase.

Mugdan presented the same slideshow at both meetings. He explained that by law, the EPA could force the city to place the tank in the park, but he recognized the city’s desire to preserve as much park space as possible. The ROD did not recognize the city’s desire to place a “head house” above ground – next to the tank – as a way to mitigate odors during tank cleaning. This structure would have to be placed in the park, with the potential for losing some park area.

While Mugdan insisted that the EPA still believes that the park is the better location, he was satisfied with the settlement. The city will be obliged to work concurrently on plans to develop the tank at both locations. If a pre-determined time schedule is not met on the Head- of-Canal location, the EPA can force the city to pivot to the park location.

The city’s first deadline is April 2020, at which time they must have finalized acquisition of the two parcels.

The proposed agreement’s additional requirements include the removal of the toxic wastes from under the pool; the city’s full cooperation with National Grid; the building of the temporary pool ensuring no loss of swimming time for the community; removal of additional toxins at the Head-of-Canal; assurance that if the tank is not ready by the time the Canal is dredged and capped, the city will perform maintenance dredging; financial penalties for failure to comply with the terms of the agreement; and reimbursement to the EPA for oversight costs it will incur as it ensures the timely completion of the tank.

Mugdan addressed fears that the city was in fact employing delaying tactics to avoid having to build the tank altogether. The city’s relationship with Superfund has been contentious from the beginning. Mugdan told the audiences at both meetings that what cinched the deal was the city’s waiving of their right “to any legal challenge of EPA’s selections of CSO controls in ROD,” and that the “agreement reflects NYC’s willingness to implement CSO retention tank element of EPA’s ROD.”

In 2013, the Brooklyn Paper reported on the city’s defiant attitude toward building of the tanks.

“The city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) told The Brooklyn Paper that sewage overflow shouldn’t be the focus of the fed’s so-called ‘Superfund’ cleanup of the canal and that the main issue is the industrial waste that has been sitting in the canal bed for decades, so it has no plans to follow the federal government’s order to build two storage tanks to keep raw sewage out of the polluted channel during heavy rain storms.”

The question of building the tanks at all will be permanently put to rest with this agreement, according to Mugdan.

However, finalization will not come before the end of the public comment period, and the EPA will have to consider each and every comment. Mugdan said the three scenarios are possible: that the public deems the agreement fair and it becomes finalized; that changes are suggested which the city agrees to; or changes are not agreed to by the city and everything goes back into limbo.

The first public comment at the Monday meeting came from Community Board 6 member Glen Kelly, who called it a “boondoggle.” He added, “this agreement will cause the city to become a problem,” referring to potential delays in the cleanup. He urged the EPA to use its power to force the city to build the tank under the swimming pool.

Many questioned the potential use of eminent domain, when a suitable location is already owned by the city just across the street. Eric Landau, Acting Deputy Commission for Public Affairs at DEP assured the audience that “eminent domain is their last resort.” He affirmed that DEP is in constant communication with Dumbo’s Alloy Development, who currently controls the two parcels and would like to build two low rise commercial buildings on the property. At a previous CAG meeting, Alloy’s president, Jared de la Valle, presented a plan in which they would donate a portion of the land to the city’s Park’s Department if they were allowed to go ahead with their project.

An unexpected twist came when Ian Defbaugh, representing Eastern Effects Studio, wondered what was going to happen to their film studio, located just south of the Head-of-Canal location. Eastern Effects owns a twelve-year lease in the building, which is now also threatened with seizure by the city, who plans to use the land as a staging area. Defbaugh explained that his company had made a million-dollar investment in the property, which is used to film “The Americans,” and employs a number of local residents.

His fears were not addressed at the April 25 meeting.