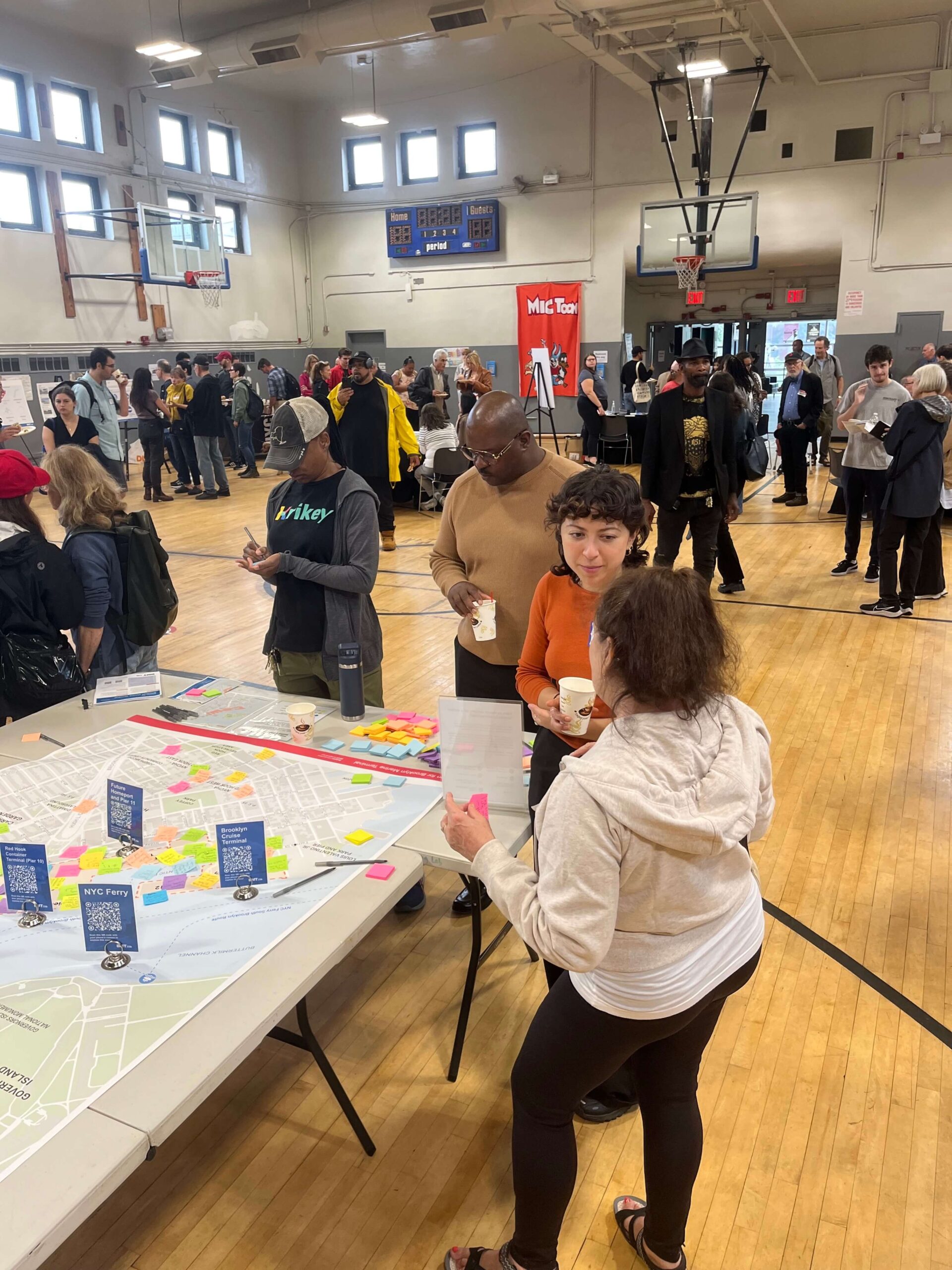

On September 28, despite drizzling rain, the Miccio Center was packed at midday for a meeting about the future of the Brooklyn Marine Terminal. Red Hook residents, members of the press, and elected officials scrambled into the senior center’s gym to: grab a coffee and a pastry or sandwich (provided by Brooklyn Bread); grill members of the NYC Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and WXY Studio (WXY), EDC’s designated contractor for community engagement on the project; and add their opinions to posters and maps about the project.

Reset, Slow Down, Listen

Outside the center’s entrance, the Brooklyn Marine Terminal Neighbors Alliance—a newly formed activist group concerned about the project—tabled, asking individuals to subscribe to their mailing list and sign a petition to slow down the project. Earlier in the morning, a tan Escalade was parked on Degraw Street, with the group’s tagline written in white on the SUV’s glass: “Reset, Slow Down, Listen!”

The workshop consisted of different stations dotting the perimeter of the gym. Each station was manned by a representative from EDC or WXY. The stations began with an overview of the project, much of which had been covered in the previous month’s information session. The stated vision for Brooklyn Marine Terminal (BMT) “is a generational opportunity to reimagine the site with a modern maritime port at its core and mixed-uses, including housing and community amenities.”

Next, attendees were welcomed to share their priorities for the project. Each attendee received two stickers to place on images that corresponded to their preferred priorities. The proposed priorities ranged from public parks and open space (very popular!) to job training (not popular!).

Transportation a concern

Another station covered the planning process for the project, and allowed attendees to pose questions they had for the advisory groups via post-its. Many questions focused on transportation concerns and how the project would take into account the ongoing BQE project and traffic. Some of the questions on the post-its were a bit confusing. “How do neighbors directly impacted have their voices heard?” one person asked, while attending one of the very public workshops meant to allow neighbors to give feedback. Other questions were relevant to the neighborhood, but not quite relevant to this project or EDC, like one about stopping the preponderance of last mile delivery operations in Red Hook.

In the center of the room, giant maps of the project site were laid out on tables so that residents could place mini-posts with their ideas for specific parts of the site. What did the community want? New parks, dog parks, and maybe even some indoor pools. But in addition to ideas, the map contained many notes focused on what was not wanted, primarily housing or more traffic.

For their part, EDC and WXY have created a clear process with many opportunities for feedback, and yet they cannot seem to calm residents’ concerns about being heard, and about high-rises filling the site. Regarding the former problem, a solution is not clear. If community workshops, feedback sessions, a task force made up of various types of local stakeholders, and public surveys do not sufficiently allow residents to voice their concerns and opinions, what will?

Housing is necessary

High-rises, on the other hand, are a legitimate concern. One attendee stated that they did not want multi-million dollar apartments on the site; in response, an EDC representative noted that housing is necessary for the city at every price point (a true, but not so consoling response).

While the city is desperate for more housing at every income level (which leads to greater affordability), one might quickly rebut that multi-million dollar apartments are usually not housing at all, as much as they are real estate investments. Meanwhile, while the city needs affordable housing most, it is often hand-tied in providing it, with few carrots to offer developers; with the city-led redevelopment of BMT, there is an opportunity for the community to request as much affordable housing as possible, but it will not come without a compromise.

The truth is—it’s rare for anyone to want more housing built nearby. After all, more housing means more traffic, more noise, an altered look of the neighborhood, and the potential for gentrification. Housing in the neighborhood will either be an altruistic decision to fight the city’s housing crunch, or an economic one, motivated by the potential for developers to help make this piece of waterfront shine, like they have in Domino Park or Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Whether or not the community and task force include housing among the final list of recommendations for the area, the biggest obstacle for a brilliant BMT is not the quick process or lack of input, but rather an opposition group that spends so much time saying “no” to the project, that they run out of time to participate. The project will likely move forward. Let’s hope it does so with the countless unique ideas residents can dream up for Red Hook, and not just the laundry list of changes they don’t want to see.