The idea of participatory budgeting (PB), which in April concluded its eighth annual cycle in New York City, is admirable and perhaps even inspiring. In practice, however, it feels a lot like New York progressive politics on the whole: somewhat dysfunctional and ultimately empty.

An exercise in direct democracy embraced by forward-thinking cities around the world, PB empowers ordinary people to make decisions that normally would be left to elected officials. Here, it allows each New York City Council Member voluntarily to set aside at least $1 million from his or her discretionary budget for capital projects proposed and selected by district residents. Thanks to a successful measure on the city ballot in the November midterms, the program will expand to all council districts for Cycle 9 in 2019-2020.

PB opens its doors to every marginalized group: undocumented immigrants, non-English speakers, children, and the formerly incarcerated all get to have a say in how we’ll spend the money. No one has to register to vote.

Councilman Carlos Menchaca, known as an enthusiastic supporter of PB, gives $2 million to the program each year. Through canvassing, flyering, and social media, his staff works to ensure that District 38 continues to lead the city in voter turnout.

In a 2016 op-ed for the Star-Revue, Menchaca called PB an “example of engaged residents using grassroots democracy to radically change the way we form government budgets. I adopted PB as I came into office with faith that it would change tired, unfair, old New York City budget habits. It has worked beyond my expectations.”

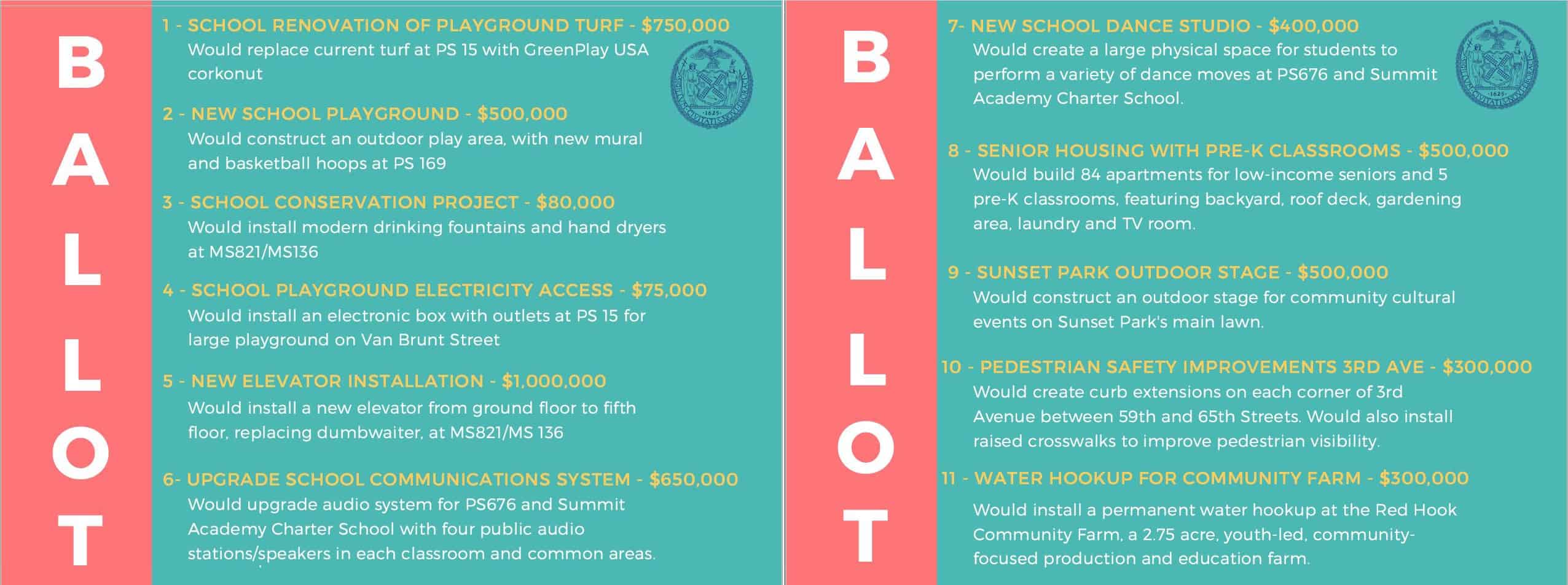

No one can doubt that many of the projects funded through PB have been worthy. But in order to understand why the program, in its current form, fails to embody its underlying goal – that is, to bring citizens into a less mediated form of contact with their government as it seeks to express their will – one only has to glance at District 38’s 2018-2019 ballot, whose contents Menchaca’s office revealed on March 19, 11 days before the start of Vote Week.

The most striking thing about the project slate is that any normal person would almost certainly want to vote for nearly everything. School improvements comprise 8 of the 11 proposals: drinking fountains, basketball hoops, a public-address system, and so on. Is there anyone who doesn’t agree that kids deserve well-equipped classrooms and recreational facilities in public schools?

What it means when capital projects of this kind appear on the PB ballot is that city government is not using the process to learn any new information about what residents might like to see in their district. City government already knows that it’s supposed to fund public schools. City government is already in conversation with public schools.

PB shouldn’t be necessary to maintain P.S. 15 or P.S. 676. That should happen in the normal course of things. But it doesn’t. Instead, PB gives the schools of District 38 an opportunity to face off in a nonviolent Hunger Games to win money that all of them should already have, and City Council gets to act like this is a great privilege. It’s democratically subdivided austerity.

The purpose of PB should be to create projects that city government wouldn’t necessarily think to pursue in the normal course of things. It should tap into the people’s unaddressed needs, but also into their dreams, their sense of fun, their whimsy.

It might mean a statue of Al Capone or Carmelo Anthony in Coffey Park. It might mean a fleet of electric skateboards for rent or an appropriately sized bathroom at Valentino Pier. It might mean a bike path along Beard Street or a network of ziplines connecting the roofs of the Red Hook Houses to Van Brunt Street and the Smith-9th Street subway. I have no idea.

If you live in Red Hook or Sunset Park, answer honestly: do you feel that you had a hand (or an invitation to have a hand) in crafting the PB ballot for District 38? City Council operates an Idea Collection Map online, where anyone can send in a recommendation, but in the end, councilmen primarily reach out to local institutions for bids. These institutions then send representatives to private meetings, where, as official budget delegates, they determine the final ballot.

In theory, the job of the budget delegates is to fashion ideas collected from the general public into actionable capital projects, not simply to advocate for their employers. According to the most recent PBNYC rulebook I could find, council districts must hold “at least three public assemblies” and “at least four meetings for underrepresented community members” in order to discover project ideas and draft delegates.

Subsequently, “project expos” will give the delegates a chance to “present their project proposals to the community through a science fair format.” If any of this stuff actually happens in District 38, we at the Star-Revue aren’t hearing about it.

In reality, most of the process seems to stay behind closed doors until Vote Week. The seats at the table go to the local schools and nonprofits, which then operate as voting sites in the spring. This presumably increases the likelihood that the winning proposals will belong to the largest institutions, which have a captive body of voters.

When the nonprofits introduce project ideas, the names of the nonprofits don’t appear on the ballot, even though these private entities ultimately will own whatever our tax dollars come to produce for them through PB. For the voter, at a glance, it all looks like public infrastructure.

This year, the Red Hook Initiative requested a $300,000 water hookup for its urban farm on Columbia Street, and the Fifth Avenue Committee wanted $500,000 to go into the development of affordable housing for seniors in Sunset Park. To be clear, the senior housing plan predates PB; in this case, PB would only provide an additional injection of funding for a preexisting project.

In March, a Menchaca staffer pointed out that one of the proposals on the recent ballot came from an individual rather than an institution. The submission asked for pedestrian safety improvements outside P.S. 503 on 3rd Avenue. This proposal was distinct from the other school-related proposals because it came from a parent at the school, not from an administrator or teacher. Still, it’s a fine distinction.

According to NYC Open Data, zero of the 22 capital projects approved through PB in District 38 since 2013-2014 have been completed thus far – not even the $85,000 community garden at the Red Hook Library from Cycle 1. In fact, only one project is currently under construction. The rest have yet to break ground.

This may not be so strange. In New York City, capital projects take a long, long time. We’ll check back in occasionally.

In the meanwhile, we’d still like to reform the way the projects are selected. Unfortunately, not all of the problems of PB can be fixed by fixing PB: as long as the city refuses to provide adequate funding for its schools, they’ll continue to look to PB to fill the gap, crowding out potentially more imaginative proposals.

Someday, though, when we’re ready to get serious about our city government, we might want to change the rules of PB a bit. First, polling stations should be neutral locations.

Second, all project proposals should come from district residents. For now, voters must reside in the district, but budget delegates can get in simply by working in the district – for example, by serving in an executive position at a nonprofit. We want the ideas to emerge from the people, not just the votes.

Insignificant as PB may be within New York City’s overall budget (of course more money should be allocated), the program at least reminds us that our goal must always be self-governance. How does one design a democracy that channels the actual will of its citizenry?

In the United States, our insufficient democratic structures – privately financed elections, a Congress without proportional representation, a presidency determined by the Electoral College, a lifetime-appointed Supreme Court with veto power over all laws – serve to legitimize a plutocracy, not to enact what ordinary people want. The task even of finding the voices of these people, accustomed to being ignored, won’t necessarily be easy, but it would start with building new democratic structures and processes. It could start here.