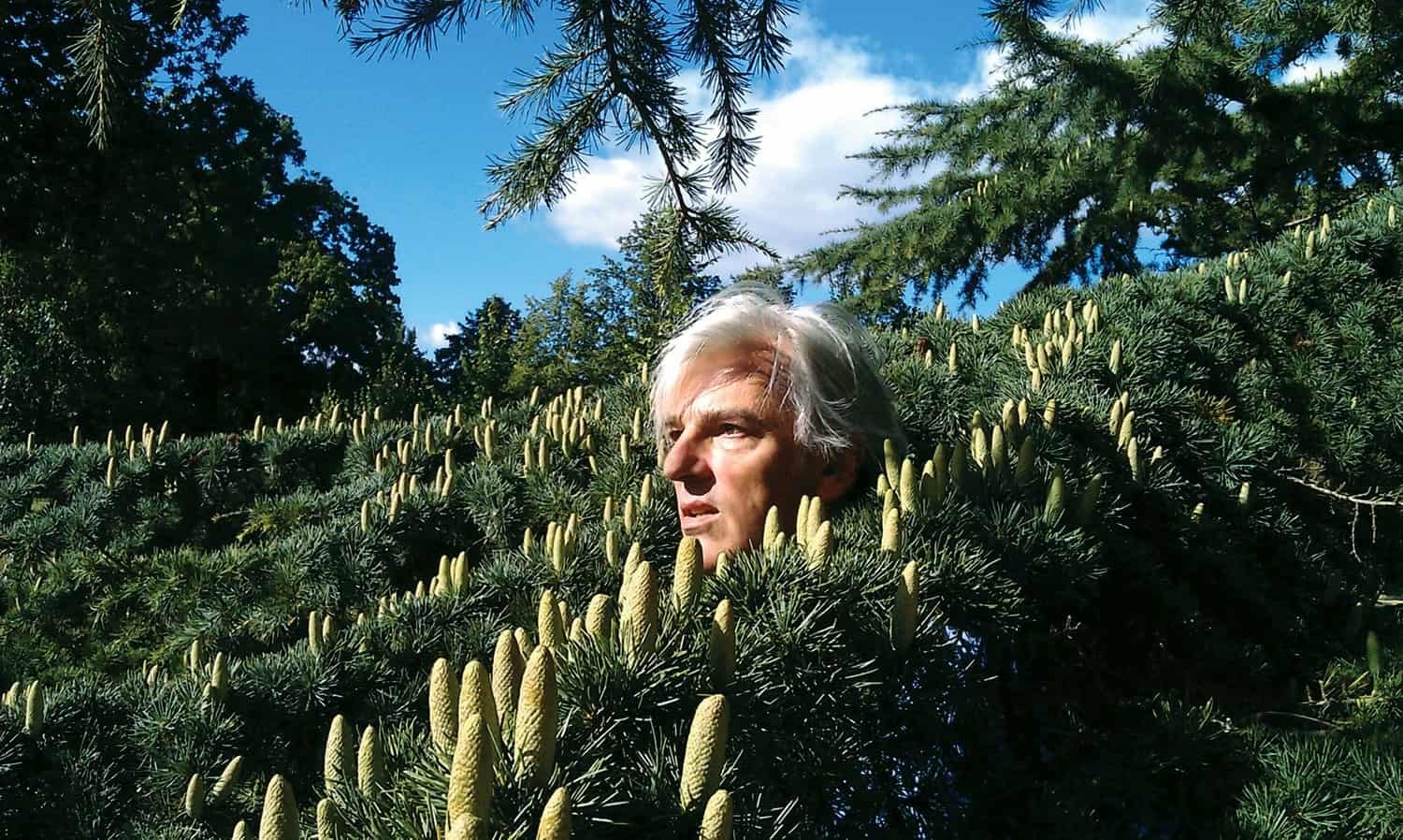

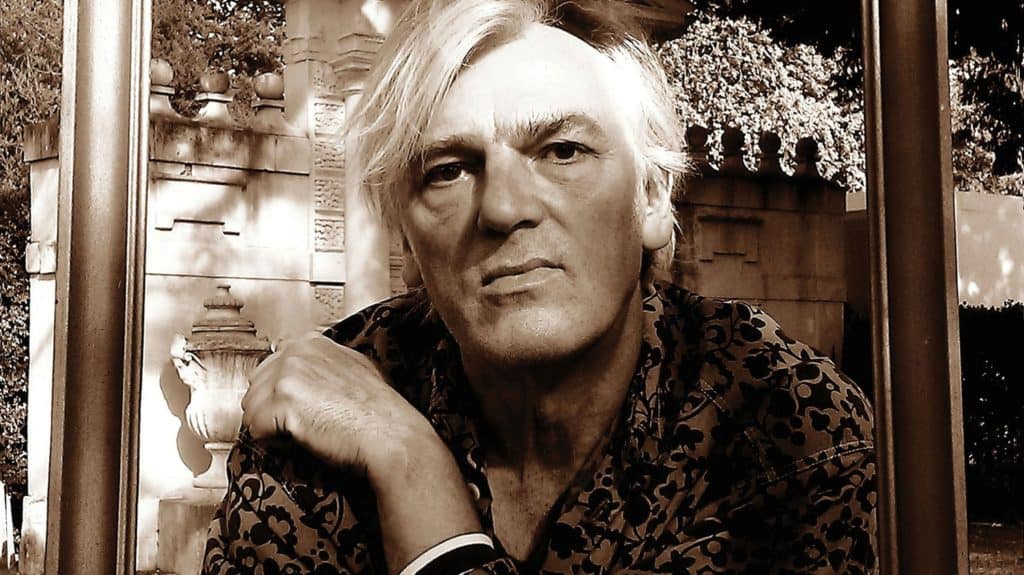

With a colorful career spanning more than 40 years, Robyn Hitchcock remains one of the world’s most idiosyncratic song writers. Born in Paddington, a neighborhood of London, in 1953, his father Raymond Hitchcock was a novelist, screenwriter, and cartoonist best known for his novel Percy. Robyn attended Trinity College at Cambridge but failed to graduate. However, it was here he began his musical career by busking and performing with a variety of groups.

First coming to prominence in the late 70’s with the seminal Soft Boys, Hitchcock’s album Can of Bees had brutal, jarring guitar lines reminiscent of Captain Beefheart while the psychedelic classic Underwater Moonlight veered into Syd Barret surrealism. Subsequent works oscillated between solo acoustic material and fuller productions backed by The Egyptians and the Venus 3, the latter of which included R.E.M.’s Peter Buck and Young Fresh Fellows frontman Scott McCaughey.

Along the way, Hitchcock has had fruitful collaborations with Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones, Nick Lowe, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, Grant Lee Phillips, The Decemberists, Jeff Mangum of Neutral Milk Hotel, Brendan Benson of the Raconteurs, and many others. Recently he has been working on a psychedelic pop project titled Planet England with XTC’s Andy Partridge.

Hitchcock has also dipped his toe into the world of cinema and has worked on various projects with director Jonathan Demme. In 1996 he appeared in Demme’s concert film Storefront Hitchcock, acted as double agent Laurent Tokar in Demme’s remake of The Manchurian Candidate, and as a wedding singer in Demme’s Rachel Getting Married.

Today, Hitchcock lives in Nashville, Tennessee with his partner Emma Swift with whom he will be performing at Murmrr in Brooklyn this Thursday, November 21. I spoke to him by phone recently about his upbringing, songwriting, time travel, aliens, and the enduring importance of The Beatles.

Cobb: Do you remember what it was that initially drew you to music?

RH: Well, I loved music ever since I was two or three. My father had bought records: Bill Haley “Rock Around The Clock” and Lonnie Donegan, who did skiffle, which was sort of an odd mixture of acoustic folk and rock and roll, a pre-beatnik kind of thing. John Lennon started with that. It was a British variation of American music with acoustic guitar, somebody playing bass on a tea chest with a broom handle on it. It was really primitive, like pre-electric punk, y’know?

My father used to listen to folk music. He’d been injured in World War II and when he was recovering from his leg injury in Newcastle lying in the hospital on morphine almost obliterated by German shrapnel, the nurses were singing northern English folk songs. He developed a taste for British folk music. So we had that in the household and early rock and roll. Then the Beatles and Bob Dylan came along, and by the time I was exposed to that, my fate was decided.

Cobb: As a child, The Beatles struck me as almost kind of dreamy, cartoon music. I know that quality filters down to much of your music. How did The Beatles strike you when you first heard them?

RH: They were just magnetic. I didn’t have an opinion about them, I was ten. I remember hearing their name and thinking, “Oh, The Beatles, that’s a silly pun.” I was a snooty kid, quite precocious, trying to think like a middle aged person. But I just heard “From Me To You” and “Please Please Me” and that was it. I didn’t think about it, I just followed it like millions of other children around the world.

And you’re right, it was sort of cartoony. They even had a Beatles cartoon over in the states, which we never had in Britain. My life was mapped in Beatles songs. I went from “Please Please Me” when I was ten to “Abbey Road” when I was 16. My whole path into adolescence and into early adulthood was started by The Beatles. As they were developing, I was developing, and millions of us were doing that. The Beatles accompanied us and they still, even more now, remain a tremendously positive sound, even when they broke down into their individual components like they did for the last three records. There was such an atmosphere, heart, and vibe to their songs. It was there, and I think children still love Beatles music. You were born in 1970?

Cobb: Yes.

RH: So, you appeared as they went. But I think the message still reaches people. I think of The Beatles as really true 20th century folk music. If you want to play songs to children, The Beatles are a very good place to start.

Cobb: You cite Bob Dylan, John Lennon, & Syd Barrett as major influences. Your music has always had a psychedelic quality. What continues to draw you to that sound?

RH: Well, to me it’s a genre of music that The Beatles, Dylan and all the other heroes of that age forged between them, The Beatles being the biggest example beginning with Revolver, but also spanning Jimi Hendrix, Syd Barrett, and many others. It was the sound that I heard and that was the genre of electric music that I wanted to produce. And it hasn’t changed. The same principle for my last album was the one that we had for Underwater Moonlight 40 years ago. The Soft Boys stuff before that was a bit more experimental and Captain Beefheart influenced I suppose. But if I made another electric record it would sound like Underwater Moonlight. I’m not sure I’m planning to, but to me that’s that sound I do. I’m a two and a half trick pony. I do that, and I do quiet acoustic with a bit of piano. I tend to lurch from one to the other across the windshield. Those are the genres. Again, I don’t really think about it until I’m asked, but if there was a category of music in record stores, there’d be a genre of music with those people, and I’d be in it. Not necessarily from time but more from sound and attitude. I suppose the nearest equivalents are Julian Cope and Andy Partridge, who ironically live about 20 miles from each other. And of course I am working with Andy from time to time on psychedelic pop.

Cobb: I wanted to ask you about that. I know you put out an EP with him.

RH: Mmm, Planet England.

Cobb: What’s your relationship with him and how did this project come about?

RH: Andy and I appeared out of the corner of each other’s eyes and were quite suspicious of each other, probably because we were already being compared. XTC was a sort of pop version of the Soft Boys; they actually were on top of the pops and had hits. We never did anything as high profile as that. The Soft Boys wasn’t really designed as a pop group. But in the late 80’s we were getting the same play on radio stations and gradually we just ran across each other. By the 21st century, when were both into our 50’s, I started going up to his house in Swindon, and we’d write round the table and record in his shed. We had a hiatus for a while, we lost touch, and then I moved to Nashville, so there was a big gap. Last year we finally finished them off. We had so much fun we started another one. We’re two songs into it I think. But I have to get over to Swindon. He doesn’t really travel; Andy’s not portable. I got him down to London once when I lived there. We recorded some stuff, but I lost the tape.

So that’s ongoing. I’m hoping we can make a full length LP, but it just depends if we live long enough.

Cobb: I hope that you do!

RH: I hope that there’s a world for us to play it to, you know. It’s not just us. We might be left and everyone else might be gone. You don’t know. But it’s nice, we’re two old guys in our late 60’s getting together in the kitchen and playing guitar, and it sort of keeps us out of trouble really. Oddly enough, he’s the only person I can really co-write with. Our minds seem to move at the same pace. Whichever way a song is going, we both seem to want to take it the same way. And I can spot the XTC chord configurations and harmonies and things. I think in our heads we’re both making Beatle music, probably.

Cobb: Somewhere along the way I got turned onto to Andy’s work with The Dukes of Stratosphere, which is quite psychedelic. So, it seems like a natural collaboration.

RH: Yeah, we both love that stuff.

Cobb: How does co-writing work? Does he suggest a line and then you chime in or vice-versa?

RH: Yeah. Or we’ll come in with a title or something. But whatever it is, so far it’s been quite easy for one of us to follow the other in a way that I can’t really do with anybody else because the way I go doesn’t really go with anybody else. So I like that, and I like the exercise of co-writing with him. My stuff is very self involved and quite dark. With him it’s more outgoing and extroverted. It’s more like, “This is gonna be fun to hum along to.” Again, more like The Beatles and less like a solo Lennon or Harrison record.

Cobb: When you’re working on lyrics, are you consciously looking for ways to tweak the ordinary? I’m thinking of lines like “you’ve been laying eggs under my skin” from Underwater Moonlight. You could’ve said “you gotten under my skin baby” but you took it somewhere else completely. “Now they’re hatching out under my chin.”

RH: Umm, I never thought of “getting under my skin.” I actually thought of somebody literally laying eggs under your skin. I had a visual image of the way you could be colonized by some insect or some other life form. It’s really sinister and creepy the way people can dominate each other. I’ve always hated cliches, and one of my guiding missions from the Soft Boys onwards was to try to find different ways of putting things. If that struck some people as awkward or contrived, then so be it. I just didn’t want to resort to stock expressions because I think they lead to blandness, they lead to the impersonal, and they lead to nothing. To me the best songs were always written in a very personal way with the singer’s language right in there, and you felt like you were listening to an individual.

Cobb: I know you paint and draw, which we can see happening in your latest video “Sunday Never Comes”, and you’ve done the artwork for several of your albums. You also reference authors Virginia Woolf & Sylvia Plath on your last album. How do other art forms influence your music, if at all?

RH: Poems, stories, pictures…if they echo with you it’s only a matter of time before they find their way into your work. Music is the most emotional way of expression for me; it’s hard to listen to a painting, so I prefer to sing if I can.

Cobb: What inspires you today?

RH: I write songs because the 15-year-old me wanted to do that so badly that I trained myself to write them. Inspiration can be from trauma, it can be from a glazed dream state, or it can be from random trivia that alights in the brain.

Cobb: You’ve sung of things as earthly as love and insects but also more ethereal themes like space, time, & the planets in our solar system: for example Mars in “Autumn Sunglasses”? How do you meld the mundane with the otherworldly?

RH: Oh, I have no idea, do I really? I guess some things are close up, some are farther away. Love is pretty unearthly.

Cobb: Do you believe in alien life forms?

RH: They exist, I’m sure, but whether they ever stop by our neighborhood is another matter.

Cobb: Where is the “Time Coast”, which you sing about on your 2017 release?

RH: Compton Bay, on the southwest corner of the Isle of Wight. It’s coloured cliffs are constantly falling into the sea, sometimes revealing fossils amid the strata of billenia. Each summer I walk along that beach, measuring my mosquito life against eternity. But even eternity isn’t forever…

Cobb: As an expat Englishman living in the USA, it seems like you have an opportunity to view things from the inside and the outside. Do you think this allows you to see things others can’t? Does any of that filter into your writing, in particular on Planet England.

RH: Being based in America helps me mythologize Britain, and the past is all about myth. The older you get, the more past you have to play with. Andy Partridge and I actually wrote Planet England in Swindon, when I was still based in London.

Cobb: Does any of it comment on the current political madness shared by the UK & the USA or are politics something better avoided?

RH: Well, it was written before all the current horrors. There’s some comments on the traditional British mindset, certainly. Politics and current affairs do belong in songs, I think, but it’s not always easy to get them there.

Cobb: Looking back at your career & life, how do you think you’ve evolved as a songwriter? Are there sources you find yourself coming back to?

RH: Well, I’m less vivid, probably less inventive, more integrated with myself. I think I’m less thinking “me” and more thinking “we”, but I don’t know if that shows. Maybe more general and less particular; though. God knows, I’ve had a very particular life. My songs are generally less grotesque and slightly sadder.

[pullquote]

Cobb: What’s different at this stage in your life?

RH: I’ve got less to prove, but fewer new tricks to do that with and less time to do that in. Everything seems as urgent as ever.

[/pullquote]

Cobb: If you could travel in time, where would you most like to go?

RH: 1949. I’d ride the trams and trolleybuses, smoke in the bars, and wait for rock’n’roll. But then…would I appreciate it?

Cobb: What does the future have in store for you?

RH: Who wants a map of the future? Ultimately: extinction and oblivion. Prior to that, plenty of work!

Cobb: Any comments on your upcoming show at Murmrr? Will you be doing it solo? With Emma Swift?

RH: Tanya Donelly writes songs that chime with me; she’s terrific! Back in our radio days I always felt we were kindred: both spooked but rocking out at times. So, I’m thrilled that she’ll be launching the show. Emma Swift will be joining both of us at various points, and I’ll definitely play two or three with Tanya, who will have a boutique string section with her: yaysville! I’m really glad we’re getting the chance to do this.

For more information about Robyn Hitchcock and to purchase tickets to his show this Thursday, November 21 at Murmrr in Brooklyn, see his website: www.robyhitchcock.com

Mike Cobb is Music Editor at the Star Revue. He also plays music, which you can hear at www.soundcloud.com/mscjr .