In early July, contractors for the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) dug up a section of Beard Street east of Van Brunt Street, prompting speculation as to whether the project (marked as a “sewer repair” on the adjacent no-parking sign) signaled the beginning of a new effort to mitigate the persistent flooding just down the road at the Richards Street intersection.

“DEP is out there now making some repairs to the sewer line in the area as well as some of the catch basins. This should help to improve drainage in the area,” explained DEP spokesperson Edward Timbers.

Workers at the site, however, asserted that the purpose of the job was to improve the sewer in advance of possible development at 280 Richards Street, despite owner Thor Equities’ admission in February that it had dropped its plan to develop a massive office park on the vacant property. Taking a break in the afternoon heat, they noted that they’d heard that residents in the surrounding area already were dealing with sewage backups.

But the flooding, the workers said, was a whole different problem. That owed to drainage, and expanding sewer capacity wouldn’t help.

Red Hook has a combined sewer system for stormwater and wastewater, so to some degree, drainage and sewage are interconnected issues. But by the majority of accounts – based on the smell – the floodwater on Beard Street is rainwater, not wastewater, although some residents disagree. The problem here, as most see it, is that, after a storm, the water won’t go down, not that it’s being spit back up by the storm drains.

Affecting local business

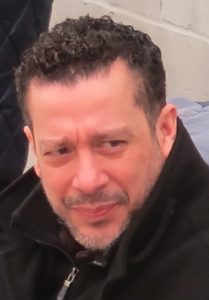

The Beard Street flooding has plagued Red Hook for years. It occurs after every major rainfall. “I’m actually amazed at how bad it is,” said David Alessandro Gonzalez, a bartender at Rocky Sullivan’s at 46 Beard Street.

Rocky’s is the business closest to the problem area, and in Gonzalez’s view, the inundation cuts the bar off from customers. “It becomes a factor when no one wants to go past this flood, and it’s really deep. Pedestrian traffic is blocked. Smaller cars won’t go through it. Cars literally turn around and leave.” On bad days, if Gonzalez has to pick up limes from Fairway for the bar, he retreats one block back to Van Dyke Street instead of taking the direct route.

If the DEP was cleaning out the catch basins closer to Van Brunt, would it make a difference at Richards, where the agency had already cleaned the catch basins last year? Gonzalez didn’t have high hopes. “I saw them dig a hole. I saw them putting in concrete. I’m not there 24/7, but I didn’t see anything that had to do with water remediation,” he commented.

The surprising thing about the flooding on Beard Street is not, perhaps, that the city hasn’t resolved it. It’s that the city hasn’t even determined why it keeps happening.

Councilman Carlos Menchaca agrees. “It’s deeply frustrating, and frankly totally unacceptable, that Beard Street continues to flood regularly. The Red Hook community needs to know yesterday what is causing this so we can fix it. We cannot live like this, especially knowing that climate change is going to make this worse one day,” he said.

The underground stream

City agencies’ indifference has made sleuths of the citizenry, and today, theories about the source of the flooding abound. Red Hook Civic Association President John McGettrick believes that the water owes to a natural stream below street level, which has existed since the days when Red Hook was a tidal marsh.

“There was, in fact, a creek – and still is, but now it’s underground – that ran pretty much along Richards Street down in this direction. A long time ago, people would be referred to in Red Hook – I guess well over a hundred years ago – as Pointers and Creekers,” he related. “And the Creekers were on the public housing side, and the Pointers were going toward the Van Brunt side, indicative of the fact that right on Richards there was a creek.”

In McGettrick’s opinion, the problem began with the construction of the IKEA at 1 Beard Street, which filled in Erie Basin’s old graving dock (or dry dock) – now a parking lot. According to McGettrick, springwater had escaped into the harbor through the graving dock every day. He wonders whether paving it over may have “truncated the flow.”

In McGettrick’s opinion, the problem began with the construction of the IKEA at 1 Beard Street, which filled in Erie Basin’s old graving dock (or dry dock) – now a parking lot. According to McGettrick, springwater had escaped into the harbor through the graving dock every day. He wonders whether paving it over may have “truncated the flow.”

Graving docks are tub-like structures that fill with water, allowing ships to enter, whereupon the water is drained, leaving the ship on blocks where it can be repaired. Carolina Salguero, the founder of the maritime nonprofit Portside New York, spent time in the graving dock as a photojournalist and knew the site well.

“It just so happened that where they located the graving dock was near an underground stream,” she recalled. “It was roaring water, and they had to have pumps running to keep the graving dock dry.”

Before the IKEA was built, consultants had to submit an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to the city. The 2004 EIS took note of the graving dock operations.

“During the ship service period the dry dock must be maintained ‘dry.’ The dock extends approximately 42 feet below grade which corresponds to approximately 34 feet below the groundwater table. Groundwater infiltration and rainfall into the dock is dewatered/removed from the dry dock using stripping pumps and discharged into Erie Basin. For each day that the dock is maintained in dry mode, approximately 12 million gallons of dewatering is required,” the document observed.

The EIS shows that IKEA was aware of the situation, which in turn suggests that its engineers would have at least attempted to find a solution for the planned parking lot outside of damming the formidable gush. “I saw how powerful that stream is, so if you put fill on top, it’s going to blow its way out,” Salguero said.

In the end, the company filled only a portion of the graving dock, permanently flooding the southern section, which has become part of Erie Basin. According to Salguero, the spring had entered the graving dock at the southern end, perhaps beyond the boundary of the present-day IKEA property.

No one is sure whether the stream that emptied into the graving dock was an offshoot of the creek on Richards Street, an instantiation of the creek itself (which may have been diverted eastward at some point), or a completely independent spring. Whether or not the two phenomena were related, Salguero, like McGettrick, also remembers what “old-timers referred to [as] the ‘Richards Street spring.’”

Thor Equities’ new bulkhead

The stream on Richards Street became a concern again after Thor Equities secured permits in 2015 to install a new bulkhead at 280 Richards, the site of Red Hook’s old sugar refinery, surrounded on three sides by Erie Basin. Most Red Hookers now put the bulk of the blame for the Beard Street flooding on Thor Equities, claiming that the problem either started in earnest or grew far worse when the developer began to prepare the site for new construction.

The old bulkhead on the pier had been, in McGettrick’s words, “totally porous.” Onlookers hypothesized that the new interlocking steel sheets bounding the property had blocked the former course of the water now gathering on Beard Street, which once had drained into the harbor through the bulkhead. Perhaps here had been the terminus of the underground stream.

At the same time, Thor Equities embedded two new outfalls on the shoreline on either side of the pier. From the outside, they look like useful points of discharge into Erie Basin that might balance out any loss of drainage from the new bulkhead. But neighbors claim that they don’t serve any purpose at all.

Stephen Kondaks lives nearby and followed the construction closely. By his account, the outfalls “go about eight feet into the property, and then they’re just capped off with some plywood.” They don’t connect to a storm drain.

Last year, a Thor Equities representative insisted that their engineers had devised the outfalls according to New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) specifications. Kondaks speculated that Thor, whose property’s future remains uncertain, had stopped halfway through the installation process. “It’s not finished. The land is not completely developed,” he pointed out.

Outfalls that link up to sewers or storm drains include, in their internal workings, a one-way trap that permits water to exit without coming back in. One Red Hook resident near Beard Street surmised that the incomplete outfalls may lack this piece, allowing surge from the harbor to wash inward and possibly to rise up through an adjacent manhole cover, a phenomenon she said she’d witnessed herself.

In April 2018, State Senator Velmanette Montgomery sent a letter to the commissioners of the DEC and the DEP, urging them to investigate 280 Richards, which she’d flagged for “excessive flooding conditions in the area” as well as other concerns. Last month, spokesperson Rodney Rivera asserted that the DEC had found “no evidence” that the “new bulkhead contributed to flooding issues on Beard Street.” The DEP didn’t offer comment on the matter.

Between 2016 and 2018, Thor Equities earned notoriety in Red Hook by leaving massive piles of loose dirt at 280 Richards after digging up the pier’s old bulkhead. Menchaca organized a meeting to give community members an opportunity to air their grievances, which included the flooding. The developer brought along a civil engineer, who declared that, based on old maps, the area had no underground streams and that, because the new bulkhead was not watertight, it could not have caused the Beard Street flooding.

The engineer freely admitted that he himself couldn’t fully explain the flooding, although he observed that “it’s a very low-lying area” and that the sewers nearby were clogged. Gita Nandan, co-chair of Resilient Red Hook, replied, “If those sewers are clogging and they weren’t clogging before, I suspect that your soil is running offsite and even that the water ought to be tested at your property line to see what the particulate matter is. If that’s running into the sewers, the sewers have no ability to take out particulate matter.”

Soon after, the DEP cleared out the clogged catch basins leading into the sewer on Beard Street. Nothing happened. The flooding continued.

Melissa Cicetti, an architect whose office overlooks 280 Richards, thinks the engineer was wrong about the bulkhead. “It changed a pattern of flow. Even though it does allow the tide to come in and out, it’s not the same rate,” she said. “The equilibrium that was there that prevented it from flooding to the degree it floods now disappeared.”

She clarified, “It’s not that what they did is bad. They had one of the best civil engineers in New York City designing the work. It wasn’t like it was done by a bunch of idiots.” Still, she believes that the alterations may have created hydrostatic pressure, affecting the groundwater table and prompting water to “percolate up from the center of the site.”

At the meeting with Thor Equities, she told them that, from her observation, water doesn’t only flow in from the street toward the bulkhead. It also “flows from your site out.”

The illegal parking lot

Cicetti also places at least a small piece of the responsibility for the flooding on the parking lot at 60 Beard Street, across the street from 280 Richards. Years ago, she observed a slapdash paving job on the former dirt lot. Blacktop covered the previously permeable surface, channeling rainwater into the adjacent street. Per city regulations, parking lots are “supposed to have catch basins and drywells,” she complained. “You’re supposed to prepare the soil underneath.”

The Department of Buildings responded to an inquiry regarding the possible code violation at 60 Beard: “DOB inspectors performed an inspection of the site today, 7/24/19, and found it is being improperly used as parking lot contrary to City records, which indicate the property is vacant land. DOB inspectors issued a violation for the illegal use, as well as a violation for a fence that has not been properly maintained.” Rachels’ Island, LLC, has owned the property since 2004.

At Rocky Sullivan’s, Gonzalez also attributed the flooding to the parking lot, but for different reasons. The sign on the lot’s fence identifies the operator as Tri-State Towing, but nearly all of the vehicles inside are large trucks and buses. Gonzalez believes that their weight has compressed the portion of Beard Street just beyond the lot through constant use, creating a moat for rainwater. He pointed to the necessity of the durable concrete bus pads now implemented at most city bus stops.

While the true cause of the flooding remains somewhat unclear, the solution may not be. The Red Hook Integrated Flood Protection System (IFPS), promised since the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, will raise and regrade Beard Street in order to facilitate the installation of a floodwall.

The problem is that no one expects the IFPS for a long time. In the meantime, absent a full-scale hydrology study by the DEP (which community members have demanded), the Beard Street flooding is likely to remain a subject of speculation – and, of course, frustration.

“I feel strongly that a forensic investigation is needed in order to know what happened and how it can be now be remedied,” advocated Richards Street resident Andrea Sansom. As of late July, the flooding continues.