“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

― Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind

In today’s sharply divided political world, Hannah Arendt’s words, (in reference to the Holocaust) ring true. Arendt’s assertion that people are not inherently evil is an optimistic worldview – the real danger for us humans is in passivity and therefore, collusion. Like many, I follow the news regarding the war in Ukraine, but I haven’t done anything concrete beyond feeling compassion, empathy and sadness. I can easily identify how I feel about the war, but I haven’t taken any action. By Arendt’s definition, am I evil? As a westerner living in the relative safety of America, a world full of bombs, chaos and death is far enough removed from my daily reality for my inaction to continue indefinitely. There are no clear pressures forcing me to make up my mind to be good or evil. I’m just living life. Did Arendt identify inaction as the very issue with humanity?

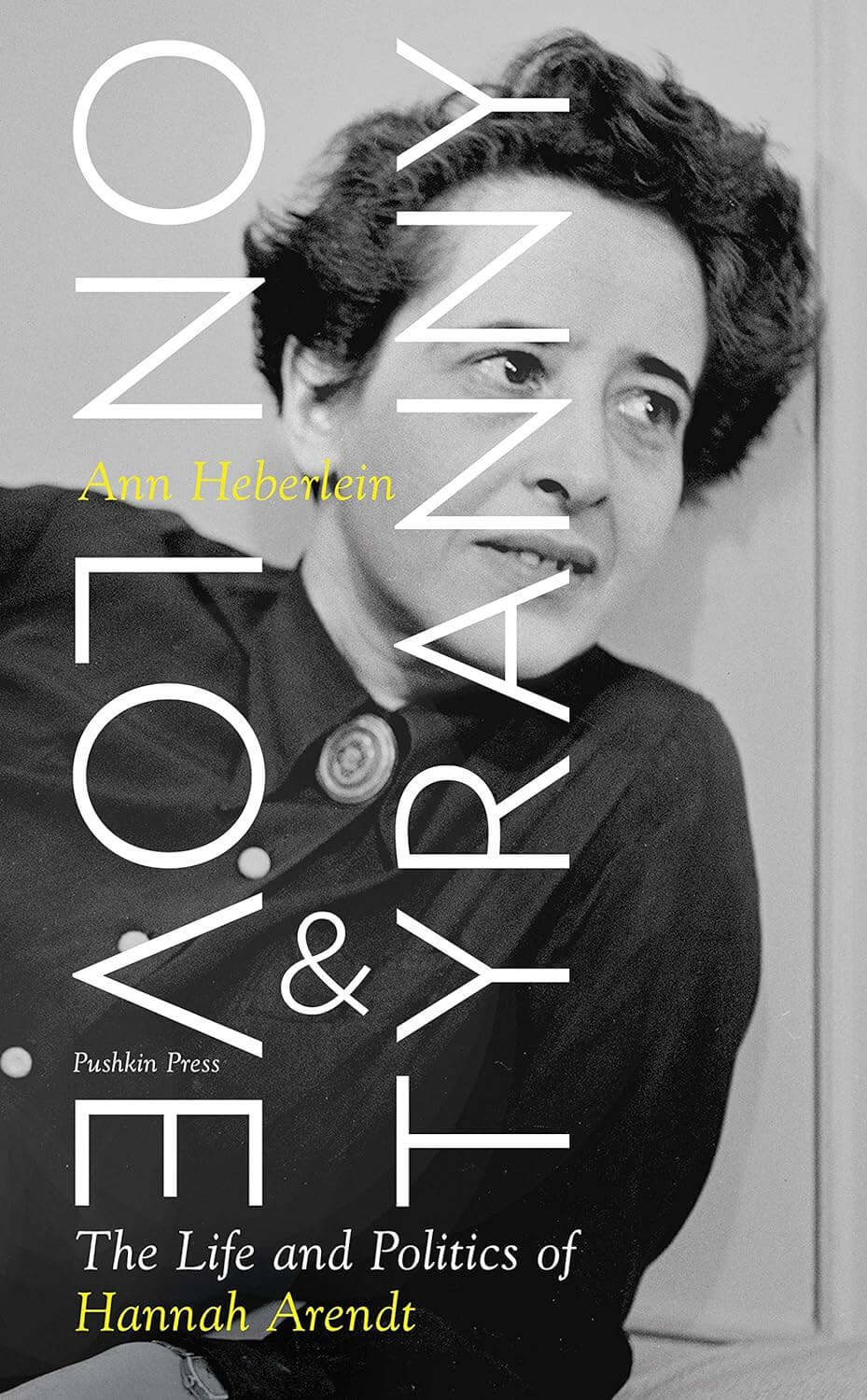

Herberlein’s brief but thorough biography (2021) of the 20th century German Jewish philosopher, political theorist, educator and writer, Hannah Arendt, oscillates between factual and philosophical, superficial and cliche. The last line of the book reads more like an inspirational plaque: “What can we learn from Hannah? That we should love the world so much that we believe change is possible, and that we should never give up.”

Despite the book’s shortcomings, I found myself engrossed. Heberlein, a Swedish philosopher, has clearly done her homework on Arendt’s influences: her secular Jewish childhood, lovers, extensive reading and her German homeland. Heberlein deftly brings to life the glittering intellectual circle of pre WWII Europe, and the many famous academics and artists who populated Arendt’s world throughout her lifetime.

Unfortunately, as strongly as the basic facts are presented, the flesh and blood woman, Hannah, remains flat to readers. Her death, in 1975, at home in her Riverside Drive apartment at age 69, takes up a mere two pages of the book. Her funeral receives a measly two paragraphs. Small idiosyncratic details are limited to Arendt’s lifelong love of smoking and many vibrant friendships over the course of her life.

Throughout the biography, Heberlein dissects Arendt’s philosophies, drawing in scholarly influences like Kant and Kierkegaard while inserting paraphrased ideas or explicit excerpts from Arendt’s books. This results in the biography reading more like a textbook or a Phd dissertation than a compelling narrative. If you’ve never heard of Arendt, this biography is a crash course. More successful biographies like Joby Warrick’s brilliant Black Flags or Jennifer Homan’s wonderfully detailed Mr. B, paint vivid pictures of both men’s (Zarqawi and George Balanchine, respectively) internal and external landscapes, comprehensive portraits of each as individuals. Heberlein’s treatment of Arendt dances into the territory of generalities, drawing readers away from illuminating personal details.

Several chapters are spent on the controversy regarding Arendt’s controversial remarks about Adolf Eichmann in her books, Eichmann in Jerusalem, but Heberlein doesn’t go much deeper into examining the backlash of this publication in regards to Arendt’s career or how Arendt internalized the criticism from the outside world. Although there are mentions of Arendt’s lifelong questions of identity due to her nonreligious upbringing, Heberlein skirts around the more pointed questions of Arendt’s Jewish heritage, leaving readers somewhat in the dark about what is one of the most influential aspects of Arendt’s life, and therefore philosophies.

Sadly, even the sexiest aspects of Arendt’s life get a clinical treatment – her on and off again affair with Martin Heidegger and her largely successful but open marriage to Heinrich Bluecher are handled through a dry lens. Throughout the biography, Heberlein attests to the strength of Bluecher and Arendt’s marriage as a stabilizing force for both of them, yet seems to contradict herself by returning to Arendt’s unresolved feeling for the much older and known Anti-Semitic Heidegger.

Arendt’s decision to never have children isn’t explored in any nuanced detail, the author cites that despite Arendt’s view of children as the true “happy ending” to romantic love, the couple felt times were too tumultuous to start a family of their own – this might or might not be true but this is the only information audiences receive in regards to the couple’s childless marriage. Arendt’s mother, to whom she was quite close also emigrates to America but her role in Arendt’s life completely drops off once arriving in America, leaving me wondering, what happened to Martha?

Heberlein’s obvious admiration and respect for Hannah’s bright mind does translate onto the pages, and Heberlein’s excitement propels the biography forward through the denser passages of text. One of the most interesting aspects of Arendt’s life is certainly her intellectual loves – the development of her own theories and ideas in conversation with the many brilliant minds she came into contact with all in spite of being expelled from her homeland. The biography makes one nostalgic for a time period before social media platforms like X, devaluing our modern discourses beyond recognition.

As the Jewish high holidays conclude this month, time spent thinking of lives lost, uprooted, forever and irrevocably changed during the Holocaust feel doubly important to honor and consider. Most importantly, however, Arendt wanted us to think. As she wrote: “There are no dangerous thoughts; thinking it-self is dangerous.”

In the spirit of Arendt, let’s all keep leading dangerous lives.