Of course conservatives hate the movies and the entertainment industry that produces them: movies are, bottom line, substantial investments of capital that seek to return profits. Thy are made to sell to viewers, and so movie makers try and give the public what the producers think it wants. Thats why there’s a massive library of MCU and Star Wars movies and shows, expensive, professional, and predictable stories without meaning or drama that people eat up. We all want some sort of safety, and these movies are safe as can be.

And they are also made to appeal to the largest number of people, and the producers have figured out that it helps to have all sorts of people up there on the screen. The term from the discourse is representation, but it’s really, simply just life. Life in a big city where a movie company is located means being surrounded by all sorts of people, that is the basic fabric of life. And since there’s a large minority in America that is absolutely furious that there are people who look and think differently than they do, there is constant loud whining about this (these aren’t controversies because there’s no sides to it).

Movies, often made by smart people, have also the prime mechanism for smuggling truly left-wing, or at least leftist friendly, ideas into the minds of mass audiences. The whole capitalism—as—organized—crime thing started with and has thrived through the movies, pictures like On The Waterfront, Force of Evil, Point Blank, The Conversation, Robocop, and Michael Clayton. And don’t even get me started on the confusion over the fantastic antifascism of Starship Troopers.

This month, the Criterion Channel might be smuggling a great, avant-garde message into living rooms all over America, via their new collection, “Free Jazz,” 12 films that either document the music or use it as a key dramatic element. What theses movies will show is that the things that musicians like Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra left here for us to learn may be complex, even hard to enjoy on the surface—free jazz as a means of form and structure depends on musicians, on the spot and in the moment, inventing things, whether it’s a fitting together notes and rhythms into an abstract structure (the way a sonata works), or expressing personal ideas and emotions. That’s not a song, but it comes from a similar place of sharing an idea about something through music. But in free jazz, it’s something more heroic, an existential carving of meaning from the face of the universe.

Yes, complex, and in terms of style often an immediate challenge to the ears. Even listeners addicted to the quantized beats of so many contemporary popular styles have little issue with the flexible rhythms of funk playing, but what about when there’s no clear rhythm, or pulse, or even a downbeat? What if instead of homophony (melody with harmony underneath) there is multiple instruments going their own ways, all at once? That’s true personal freedom, not the popular kind where you don’t pay taxes and can park your car for free wherever you like, but the personal kind, freedom of thought and conscience.

That type of freedom is appealing to many people, and free jazz is often unexpectedly compelling to people who never listen to mainstream jazz to begin with. There’s certainly an overlap in sheer sonic quality to punk and noise music—free jazz predates them both—and underneath it all is the anarchy. That’s not anarchy in the sense that anything goes (not all free jazz is good and one of the most frequent reasons it fails is because the musicians don’t reign in every impulse or shape the results) but in the sense of a society without rulers, but with leaders, and devoted to a musical mutual aid. To play free in a group means listening to what everyone has to say.

Living in cities makes a difference, I believe, and all the mutual aid groups in New York are philosophical cousins to free jazz. I’m sure there’s no data behind this, but I’m also sure that free jazz doesn’t have much appeal to resentful whites who vote Republican—free jazz is inherently antifascist—while it thrives in pockets in urban areas, large and small. Streaming on Criterion means those pockets will reach into every home where one of the movies is playing.

In terms of who is drawn to the music, there’s a brief and fascinating scene in the documentary Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise where Ra and the Arkestra are playing in a bar in Philadelphia, within arm’s reach of the patrons who are dressed up for a night out. The incongruity between the social scenes of the band and the bar disintegrates when you see how hard the audience is listening.

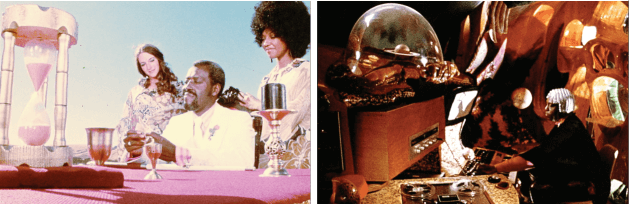

Ra was one of the absolute greats, showing the world how logical it is to mix Fletcher Henderson charts, songs from Disney films, doo-wop, and free improvisation. His whole social and political conception was about freedom from the racism of society, and those are on display in his science fiction movie, Space Is the Place. It’s an incredible movie, not necessarily, or always, good, but incredible. It mixes together blaxsploitation, Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, concert film, action, and more; there are professional actors and obvious amateurs; it is serious about its ideas but good humored, and is unlike anything you’ve ever seen. It’s a visual narrative drama of Ra’s music making.

The lineup also includes exceptional documentaries likes Ornette: Made in America, Milford Graves Full Mantis, and the recent Fire Music. One of the real finds is another fiction movie, Les stances à Sophie, a 1971 French film that has a score by the Art Ensemble of Chicago. For that movie, that band cut the track “Thème De Yoyo,” with the great Fontella Bass singing, the AEC laying down the funk with the best of them and also blowing away the bar lines with explosive freedom.

What will this all mean to home viewers encountering this music for the first time? One thing is the cementing of the sophistication of these artists, their skills and thinking, even as the way they choose to be in society may be far from what the average person desires—there’s Sun Ra’s communal house, and there’s also the Art Ensemble, which had to stay at campgrounds and pitch tents during their first tour of Europe because they didn’t have the money for hotel rooms (not in the movie—many of the members of the AEC had been in the military, and trumpeter Lester Bowie recommended army training to aspiring free jazz musicians so that they would have the survival skills).

I expect that the great humanity of this music will come through, that it’s all about experiences of life, about thinking that the most beautiful thing is to express yourself sincerely and honestly, and to be thoughtful about what you want to say, and say the thing that will mean the most to the largest number of people. That’s not the predictability of a rhyme, or a song about yet another heartache and heartbreak. It’s about saying, “we’re all in this together,” and trusting that, even in the American of 2022, there’s still a good number of people who think that, rather than just ones who resentfully hate anyone different than them. There’s safety in those numbers. There’s safety, too, in freedom.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/