In art music (meaning music not designed for mass commercial success), there used to be a general consensus about forms and styles. That’s obvious when you look at classical music, but also things like folk music (in the English speaking world) and the blues; things were generally done within certain guidelines and outliers were less revolutionaries than eccentrics and avant-gardists, working to extend tradition, not refute it.

This all started to change for classical music around the turn of the 20th century—there was Luigi Russolo and his noise music—then much more so after World War I and drastically after World War II. Since 1945, there hasn’t been one tradition in classical mu-sic, but multiple ones, some of which (John Cage, electronic music) are barely within that tradition, if at all.

A curious thing to me is that the same cannot be said of jazz. The music came about lat-er and there’s certainly a sociological argument to be made that it itself is one of the fallouts from World War I, both psychologically and materially via James Reese Europe’s Harlem Hellfighters band’s presence in Europe for the war. From 1918 on, jazz has added new styles that build on the previous ones at the pace of modern life, an evolution rather than a branching away or a disassembly and rebuild. Even the free music revolution of the 1960s and the rock and funk of Miles Davis and others in the 1970s didn’t question jazz in any fundamental way, they just extended it further.

This isn’t a bad thing, and comparing this history to classical music is a useful way to see that advantages and drawbacks of these differing paths. Classical music, stylistically, has been fragmented for the past 80 years, which has meant some truly extraordinary breakthroughs that questions the very nature of music, sound, and time—that’s the legacy of John Cage, Morton Feldman, Arvo Pärt, Alvin Lucier, electronic music, etc. It’s also meant a kind of dissipation of intellectual and aesthetic resources that has produced an accumula-tion of great music but few transformational works, ones that redefined the possibilities of compositional thinking and instrumental playing. The last was György Ligeti’s Etudes, which are almost 30 years old.

Jazz has had a pretty uniform aesthetic since it began, marked by progressive ideas that at first encounter have seemed outside of the music, but that in retrospect are easy to see as the natural development of the music’s possibilities. Cecil Taylor is a great example, a musician who seemed to be at odds with jazz at first but, through exposure and close lis-tening, clearly connects in a straight line to Duke Ellington, just as one of his great musical partners, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, was a logical and even inevitable development from Charlie Parker. Being able to hear those origins in Taylor and Lyons is one of the great pleasures in being a jazz listener.

There were arguments between the mainstream and the avant-garde in the ‘60s, and the mainstream and rock and funk in the ‘70s. Those weren’t won so much as they disap-peared in the face of the clear evidence that jazz could mix with, work with, and incorpo-rate music that was happening around it while keeping the line of history going. And again, that dialogue with history that takes place inside the music is profound and unique, a simul-taneous popular and art music that celebrates its own life in a beautiful and invigorating way every time it’s played.

This has meant, though, that jazz tends to drive an idea to stagnation, even death, inno-vations at first vibrant then turning baroque, then rococo, finally decadent. This happened with the formulas of swing and hard bop, and is always a danger with free improvisation, which can turn into a series of hollow gestures. And my accumulated listening to the 21st century has been raising warning signs about some trends that need some rethinking:

– Before IDM there was EDM, and the daring, complex rhythms from Autechre and Squarepusher were good. So good that jazz drummers like Tyhshawn Sorey began to replicate them live, extending virtuosity and expanding the rhythmic possibilities of jazz—already a rhythmically sophisticated music. This moved from a flow to bro-ken rhythmic patterns, compound meters that have become something of a way to prove bona fides, played not because they make any sense but because they identify the player as a certain kind of musician. This is mannerism, and has become compli-cated in an unmusical way, discontinuous to the point where it comes in irritating fragments.

– There are vocal records, and singers, many good ones, and then there’s albums from instrumentalists that drop in a singer for a track or two. This is invariably a mistake. The vocalist changes the sound of the group so much that these tracks never fit with the rest of the album and don’t show a clear musical purpose. There’s also the prob-lem with the songs themselves, which are never on the same level as the rest of the album, often made in a way that accommodates the singer rather than having them fit into the group, and that lyrically are sophomoric. That’s a high school sophomore.

– Since Bix Beiderbecke sat down at the piano to play “In a Mist,” jazz has adapted many great structural and formal ideas from classical composers. But, with a very few exceptions, this has meant borrowing from the same small group of composers for the last 100 years: Debussy, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, some Bartók. But what about the music, as seen above, since WWII; revolutionary ideas in spectral harmo-ny, the timbral possibilities of electronic music; minimalism, microtonality? One of the exhilarating things about the Ligeti Etudes is how they incorporate Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell (and African and Asian music) into the classical tradition and not only renews the tradition but establish new ways to play the piano.

It’s worth reflecting on that this year, which is Ligeti’s centennial. He was a music student, and when he escaped communist Hungary he taught in the West, but there’s nothing aca-demic about his thinking, it’s all driven by his personal curiosity and the simple pleasure of making the sounds he imagined in his head. Academia took over jazz training in the last century, and pretty much every jazz musician born since 1970 has been through the con-servatories. They come out as hellacious instrumentalists, but often disregard the original lesson of jazz education: learn everything, then forget it. Do your own thing, be a trend of one.

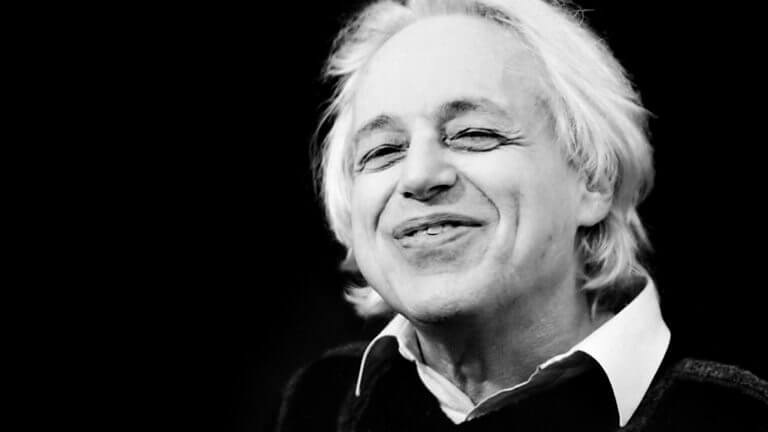

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.