In December, NYU Langone Health, the academic medical center at New York University, released the Red Hook Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment (CHNAA).

The Red Hook report was compiled in October by a consortium of six local nonprofits: the Alex House Project, Family Health Centers at NYU Langone, Good Shepherd Services, NYU Langone Health Department of Population Health, the Red Hook Community Justice Center, and the Red Hook Initiative.

Initiated under the NYU Langone Health Community Service Plan, doctors and public health experts deemed this CHNAA “particularly important because readily available data for Red Hook includes more affluent neighboring communities, thereby masking pockets of poverty and need.” New York state law requires that hospitals develop community service plans every three years.

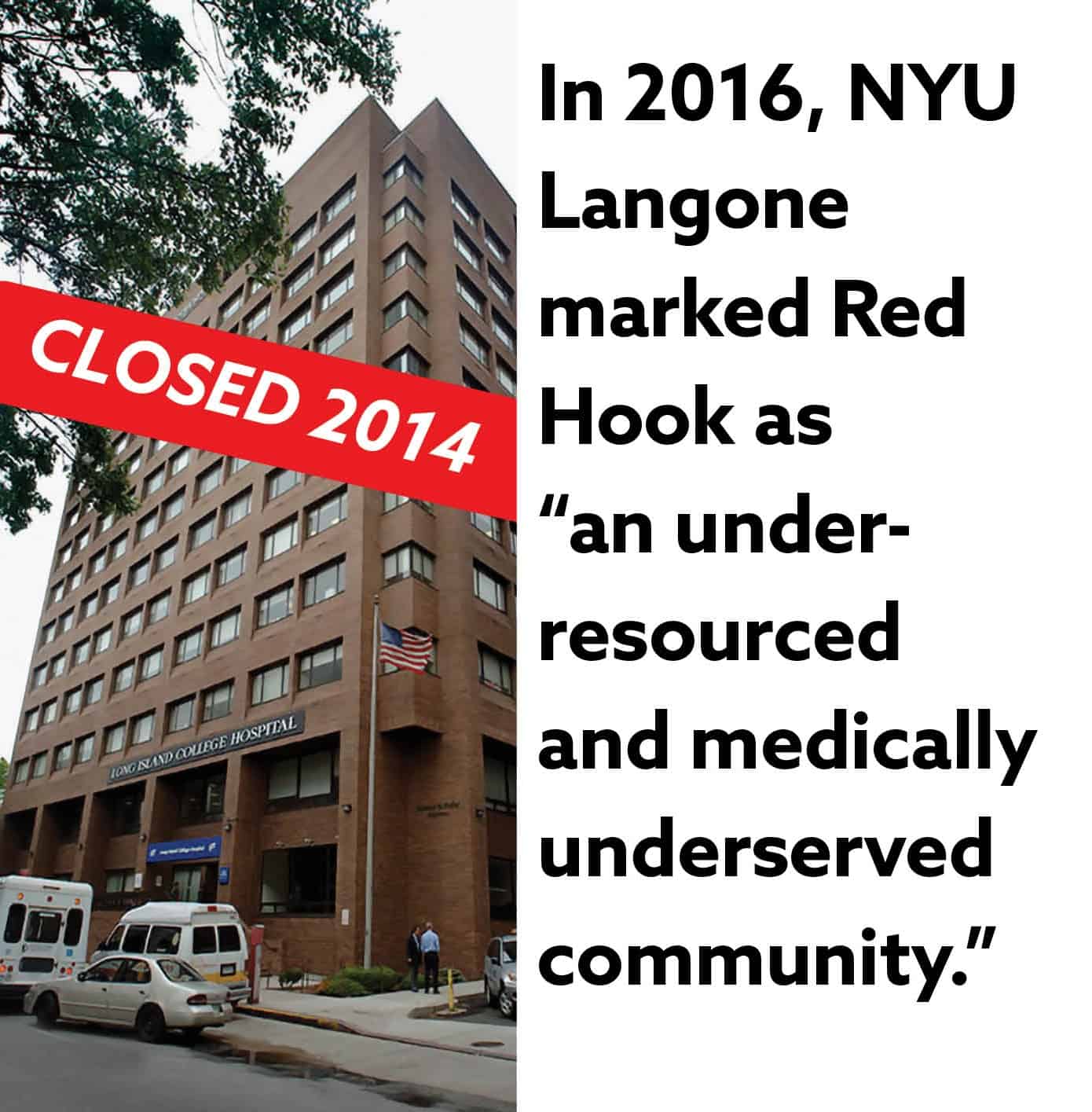

In 2016, NYU Langone marked Red Hook as “an under-resourced and medically underserved community.”

In 2014, the State closed and sold off the closest hospital to Red Hook, the Long Island College Hospital, despite Red Hook already being named an underserved health area. NYU Langone was chosen by the new developers of the hospital property to provide an emergency health facility, required by the State.

The CHNAA team began by reviewing census figures and preexisting health information gathered by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and other agencies. It then supplemented this data by conducting local surveys, holding small group discussions, and organizing seven “dot voting” events, in which participants used stickers to mark their three most pressing health concerns from a list of 12 on a poster. In total, more than 600 respondents — people who live or work in Red Hook — took part in the project.

CHNAA polls singled out asthma as Red Hook’s top health concern, emphasized by 45 percent of survey participants, who “made the connection between housing conditions and asthma in the small group conversations,” citing “inconsistent heating and cooling, mold, and cockroaches and rats” as causes or exacerbating factors. The next biggest problems — noted by 35 percent, 31 percent, 31 percent, and 29 percent, respectively — were stress/anxiety/depression (as a single category); diabetes; smoking; and substance use, including alcohol.

“Needed home repairs, rent increases, housing insecurity, safety concerns, and over-policing” appeared to play a role in Red Hook’s mental health issues, which in turn seemed to influence the neighborhood’s substance abuse and alcoholism. The CHNAA also observed that there were “more alcohol retailers in the area compared to the citywide rate.”

Among the community’s needs, housing loomed large for 48 percent of survey participants, who highlighted the urgency of improvements within the Red Hook Houses and the importance of affordability. An equal number of survey participants wanted more job training and educational opportunities, while 35 percent hoped for better access to healthy foods.

Smaller numbers of residents believed that more public services should be offered in Spanish and Chinese. “The Cantonese-speaking small group reported safety and violence as a major concern” and described “being afraid to answer their doors or go out early in the morning or late at night.” Meanwhile, the “young parent small group reported police interactions as the primary contributor to stress, anxiety, and depression.” The fear of gentrification also “came up at various points in the assessment.”

For solutions, many people in Red Hook reportedly look to “peer-to-peer programs,” such as those offered by the Red Hook Initiative; “holistic strategies” that can address “a number of related issues at the same time,” like Mayor de Blasio’s private-public partnership Connections to Care; and “advocacy and organizing.” It’s not known how many respondents endorsed these approaches, as the CHNAA didn’t provide specific figures for the “Connecting Strengths + Needs” section of the report.

In its conclusion, however, the CHNAA team stated that it is “exploring opportunities to implement these strategies to address the community’s top health needs” and even “responded to needs as they came up during this year-long process. An existing education and home assessment program for people who have asthma and are on Medicaid was expanded to Red Hook. Materials about quitting smoking and lead exposure were also distributed to residents through CHNAA team organizations.”

The CHNAA is available for public download at redhookchnaa.wordpress.com, alongside additional materials that detail the report’s methodology. These documents break down combined data sets into smaller subgroups, revealing stark differences between Red Hook residents (528 surveyed inside and outside the Red Hook Houses) and Red Hook workers (66 surveyed), and between NYCHA tenants and those in private housing.

For instance, people surveyed outside the Houses (including workers at the non-profits) believed community-based organizations to be Red Hook’s greatest strength, while NYCHA tenants — the primary population served by those organizations — cited affordable housing instead. A plurality of Red Hook residents (47 percent) identified asthma as the most significant health issue in the area, while Red Hook workers (45 percent) claimed it was substance use.

Residents and workers also disagreed on the services most desperately needed within Red Hook, with the former (51 percent) petitioning for “home repairs to address mold, pests, lead, and other problems” while the latter (52 percent) wanted “adult education and job training-placement” for Red Hook. Only 26 percent of Red Hook workers picked home repairs as a central need for the community despite a crisis of deterioration and lead exposure at NYCHA. Professor Sue Kaplan at NYU Langone confirmed that, of the relatively small number of workers who participated in the survey, most worked for the nonprofits that had helped put together the CHNAA.

One Comment

Good afternoon, back in January of 2018, the 18th to be exact, I was cat scanned, given MRI’s and was diagnosed with a tumor on the right side of my brain. it was pretty large. I started working in Red Hook East Development back in July of 2012. Since working there at the management office, I suffered depression, anxiety attack, headaches and other things that just wasn’t normal. you should not be working at a place and always feeling sick. those buildings are old, paint peeling, place not up keep and I think that is why I got sick. I wanted to check more on it but I was transferred to another site. I have a lot of doctor bills and I really don’t feel that these developments are healthy or safe. I would like to get some help, but for now, I would like to be anonymous.