The How Many Stops Act, which includes a bill that requires New York Police Department officers to record the race, age and gender of the civilians they approach during investigative encounters, officially took effect on the first day of July. (The second bill requires the NYPD to report when a person denies consent to be searched.)

Previously, officers were only required to collect information during “Level 3” encounters — a stop due to a reasonable suspicion that the individual has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime, during which officers have legal authority to detain or prevent the person stopped from leaving — but will now have to also report Level 1 and 2 stops. A Level 1 stop is when police request information from a person without suspecting them of a crime, while a Level 2 stop means the officer has begun to suspect that the person has committed a crime.

The bill went through some political rigamarole earlier this year: After the city council passed the bill in December 2023, Mayor Eric Adams — a former member of the NYPD and a staunch supporter of the police department in his role as mayor — vetoed the bill, but on Jan. 30, the council overruled the mayor’s veto with a 42-9 vote.

Advocates for the bill say it is necessary to address over-policing of people of color. According to a 2023 report from the Federal Monitor, 97% of people stopped by the NYPD’s Neighborhood Safety Teams were Black or Hispanic.

“New Yorkers understand implicitly or explicitly that Black and Brown communities experience more policing. You see, hear, and feel it across the city. Yet the data for these critical interactions that hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers experience with the NYPD each year is far from complete”, Daniela Gilbert, director of the advocacy group Vera’s Redefining Public Safety initiative, wrote in an email. Vera is an organization that works to end overcriminalization and mass incarceration of people of color, immigrants and people experiencing poverty. “New Yorkers deserve to have a full picture of how their encounters with law enforcement are represented and a full accounting of all NYPD stops and investigative encounters in our communities,” Gilbert added.

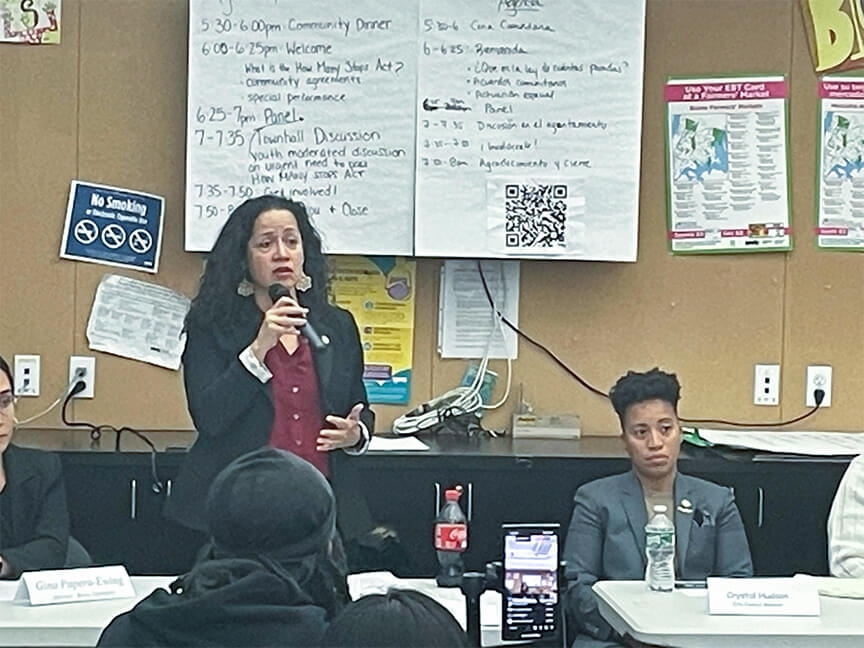

Alexa Avilés, council member for District 38 and a lead sponsor of the bill, noted that the communities most affected have been calling for a law like this for years.

“The How Many Stops Act is common sense, good government policy. The data on Level 1 and 2 stops and consent searches collected via these two bills is an essential step toward developing much-needed policies with the goal of both protecting the constitutional rights of the public and uprooting long-standing and systemic issues within the department,” the council member wrote in an email.

Critics, including Mayor Adams, have primarily objected to including Level 1 stops in the new law. Earlier this year, the mayor said it would take too long to log the information, delaying police investigations. According to the police, the problem is the amount of Level 1 encounters — more than 3.2 million in 2022, Michael Clarke, the department’s director of legislative affairs, told the City Council in March of last year — and that such encounters often are fluid and fast moving. The Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice and the New York Police Department did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

However, the many stops that go unreported is one issue that supporters hope the bill will address.

“With such a staggering number of encounters between New Yorkers and NYPD going completely unreported, data trends that could affirm lived experience and help us craft good policy to protect our neighbors remain in the dark,” Gilbert wrote.

After the bill passed, the police department had about five months to develop the tools and strategies to record all levels of encounters. No details have been shared of what those tools and strategies look like, but during a July appearance on “Mornings on 1,” Adams shared that the NYPD is prepared to comply with the new requirements, saying, “As in any new initiative, there may be a few bumps along the way, but we’re going to do what the law calls for us to do. The time for me to raise my concern was raised. Now that it’s law, we will move forward. That is how we’re always going to operate.”

Avilés is critical of Adams’s response to efforts to improve transparency and equitable treatment of the public within the NYPD.

“The mayor took a spaghetti-at-the-wall approach to fearmongering around this legislation, hurling lies and producing propaganda at a breakneck pace. It would take days to refute each and every point, but I’ll stick to one of the most irresponsible,” she wrote, adding, “The administration regularly accused this effort as having a dangerous byproduct of bogging down officers with paperwork. I would ask detractors of the legislation to listen to the NYPD’s own Deputy Commissioner, who in a PIX 11 interview on June 28, said implementation requires’ minor policy operational changes. We didn’t have to do much with technology. Just a tweak.’ “

Official numbers don’t have to be made public until October (after which they will be shared on a quarterly basis), and the City Council has not received enough information from the police department as to how the new requirements are playing out, according to Avilés.

“We are working to ascertain more details as to how implementation of the legislation is going,” she wrote in an email.

The new requirements can have implications beyond increased data collection of who is stopped by police in New York. Gilbert, whose organization Vera works across the country, highlights Denver as a city that used data to change its traffic stop policy.

“Communities and legislators need to know what stops are the most common, need to take the social costs of policing seriously, and need policies and practices that will protect all residents, without over-policing Black and Brown people,” she said.

The How Many Stops Act, she said, is, therefore, “not the destination; rather, it’s a step in the process of reducing the overreliance on policing to produce public safety.”

Author

-

I’m a New York-based journalist from Sweden. I write about the environment, how climate change impacts us humans, and how we are responding.

View all posts

I’m a New York-based journalist from Sweden. I write about the environment, how climate change impacts us humans, and how we are responding.