Baseball seems determined to drive away as many people as possible. After seeing the mantle of the national pastime snatched away by football, the MBAs and lawyers who run the game decided the best way to get back into fans’ good graces was through interminable games built around clown-car bullpens (one pitcher on the roster to face one batter before getting pulled) and keeping as many balls out of play as possible. Advanced metrics and front-office Moneyball tactics further pushed the game into a chase for robotic, data-driven efficiency. And to really drive the dourness home, players bully and retaliate against anyone who shows even the slightest hint of joy in hitting a towering home run or excitement when closing out a particularly tough inning. To do that is to get beaned, hard, to be reminded of their place — and how to play the game the “right way.” Which means with as much fun as filing your taxes, I guess.

[slideshow_deploy id=’12969′]

None of that accounts for the issues baseball has had off the field. Lack of racial diversity. A youth pipeline dominated by cost-and-time-prohibitive pay-to-play travel teams. Major League Baseball’s billionaire owners’ profits-at-all-costs tactics making small-market teams uncompetitive and, most recently, blowing up the minor leagues in a restructuring that eliminated 40 teams, relocated others, and upended (if not obliterated) dozens of communities’ only connection to pro baseball.

It gets harder and harder to be a baseball fan each season. And the COVID-19 pandemic keeping fans out of stadiums hasn’t helped. (No, paying for a cardboard avatar to attend in your stead isn’t the same — even if it boosts owners’ bottom lines.) Yet, even if the game feels increasingly unrecognizable, its lure is strong — especially if you grew up playing it, watching it, or bonding with friends and families over games and rivalries. There’s a beauty and primacy to the sport that connects generations of fans and continues inspiring devotion to a game that steadfastly refuses to love us back.

But that’s in America. In Japan, where baseball is a national obsession, the sport inspires something like religious fervor. Coaches dedicate their lives to the game like cloistered monks, while players straddle a line between seminarians and samurai; teams are akin to sects, stadiums the temples. “Even baseball was adapted into a martial art when it was imported from America,” says the narrator of the 1962 film Nine Players and Society. The stereotypical hyper-efficiency and subsumption of the individual that often colors Western views of Japanese society are also present in its baseball culture, but so are open, often intense displays of emotion: coaches screaming at players for botching a play, players bawling after a tournament loss, fans thrashing in ecstasy and pain. And like in America, Japan is wrestling with how to adapt baseball to a changing world without losing what’s at its heart. In the U.S., that spirit is moneymoneymoney. In Japan, it’s more existential and metaphysical: discipline and spirituality and heritage.

This struggle — and the generations of players and coaches it has informed — forms the emotional core of Ema Ryan Yamazaki’s excellent documentary Koshien: Japan’s Field of Dreams, available Apple TV, iTunes, and Amazon March 2.

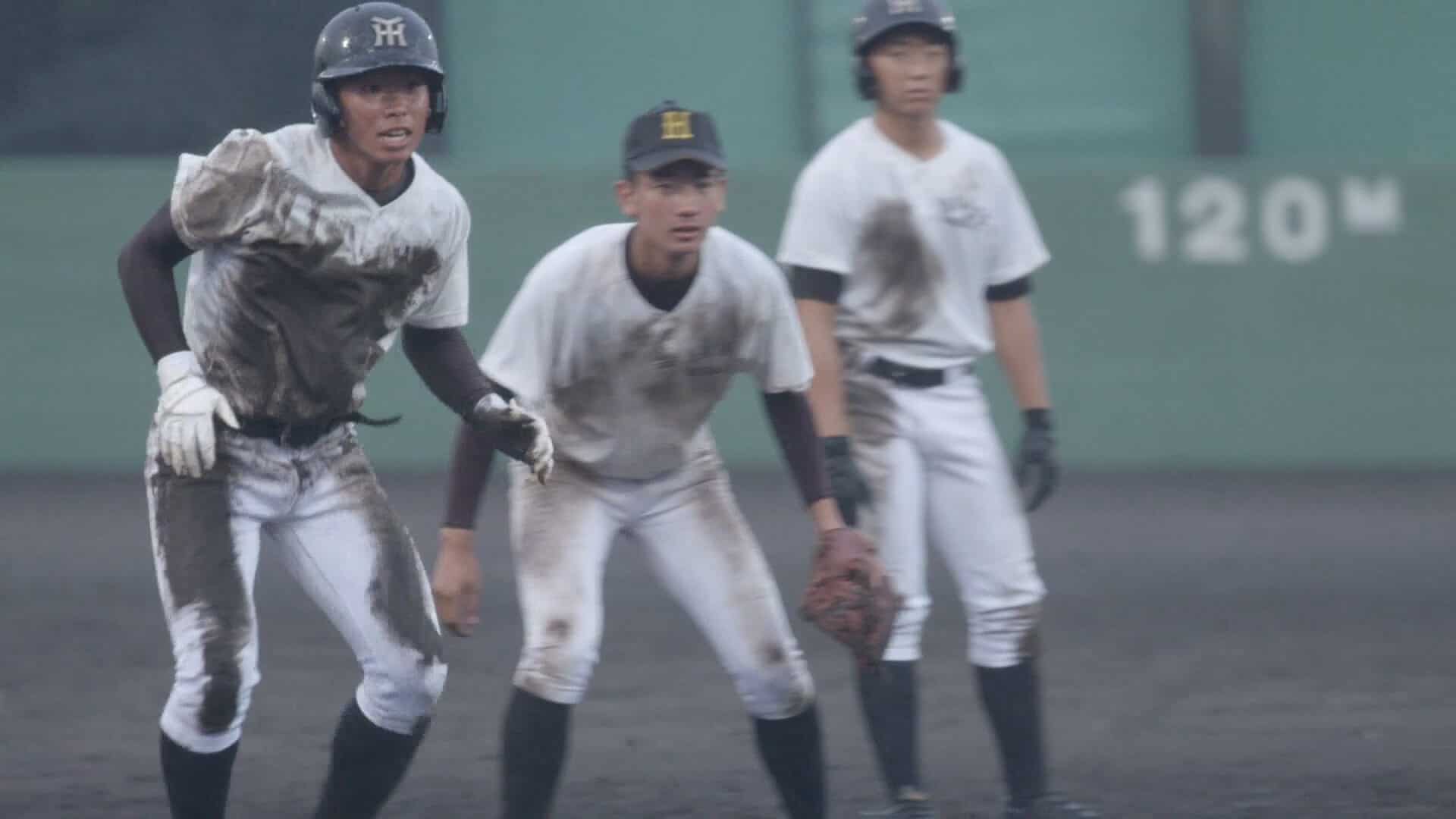

The film is framed around the annual Koshien high school baseball tournament, played every August in Osaka. It’s also one of the biggest baseball events in the nation, with one team from each prefecture competing in the tournament. (There are roughly 4,000 high school baseball clubs in Japan; only 49 make it to Koshien.) And if you think this sounds like the Little League World Series, you’d be right — if the Little League World Series was a one-and-done tournament played in front of a combined million fans at Yankee Stadium. And just getting to Koshien represents a monumental achievement: teams must compete in one-and-done prefecture tournaments to earn the right to play there.

“Koshien, the colorful national high school baseball tournament that captivates Japan every summer, provided an ideal context – helmets in a perfect line, strict adherence to rules, team-first mentality – for an extreme microcosm of Japanese society itself,” Yamazaki says in her director’s statement. “As a society’s strengths may also be its weaknesses, in recent years Koshien culture had been forced to reexamine its values.”

She explores that reexamination by following Tetsuya Mizutani, the coach of Yokohama Hayato High School, as he prepares his squad to compete for a spot in the 100th Koshien tournament. He’s been to Koshien once, in 2009, and is desperate to return. He drives his teenage players hard, neglects his family, and places everything a distant second to baseball — and expects the same of his squad. “I want to remain a stubborn man of the 20th century,” he says. “So, I don’t plan to change my ways.”

Mizutani is contrasted with Hiroshi Sasaki, one of his former assistant coaches who became head coach of Hanamaki Higashi High School. Sasaki is similarly demanding with his players, but as a younger man he often takes a gentler touch, speaking with his team and not at them. We see him using a smartphone to help diagnose an issue with one player’s swing, and we get an extended scene with him tending his ballpark bonsai garden. Mizutani sends his son Kosho — who is rabid for baseball but whose father has never seen play — to be part of Sasaki’s squad. And that’s likely for the best: Sasaki is progessive and 21st century in every way Mizutani is stuck in the past; he coached Shohei Ohtani, now an MLB superstar for the Angels; he has been to Koshien nine times.

The ghost that haunts these men’s world is legendary coach Tsuta Fumiya, who won Koshien three times in the 1980s. “I’ve coached baseball with all of my heart at the sacrifice of my family,” he says after winning the tournament. “It’s just the way of an old-fashioned guy.” Another part of his way: punishing players who don’t hit during practice. Naturally he’s a hero to Mizutani: “Tsuta-sensei’s hardships, passion, and dedication to achieve his dreams created a model for all of us to follow.”

The toll of that inspiration can be seen in Mizutani’s cold relationships with his wife, children, sister, and mother. But it’s the student-athletes — who often seem to be attending military school rather than high school — where the toll is most striking. Yes they line up their shoes, helmets, and gloves in a ritualistic act of discipline. And yes they’re expected to dedicate every waking moment to improving their skills and usefulness to the team. But the spirit of selflessness this is meant to invoke weighs heavily on the teens, emotionally and physically.

One senior desperate to make the Hayato A team is seen stuffing himself with rice to gain weight in, I guess, an attempt to make him a better hitter. “I just want to chase the ball,” he says. “It’s all I need in life.” The pressure this puts on him — compounded by the pressure Mizutani puts on the team to make Koshien — turns the teen into a player who overplays ground balls, makes sloppy mistakes, and struggles at the plate. He doesn’t make the team and is duly crushed to see his sacrifice and determination amount to nothing.

We don’t get quite the same insight into what life is like on Sasaki’s squad, though what we do see is enough to demonstrate he’s open to moving away from the worst traditions — like doing away with the mandatory-shaved-head rule — while retaining the best of the sport: the rigor and discipline that molds his students, the connection being on the team forges with community and history, the thrill of success and pain of defeat.

It’s a cliche to say that, in Japan, baseball is life, but that’s the reality in Koshien. Yamazaki captures its everyday ubiquitousness, especially when the tournament begins, but it’s the access she has to the teams and players that makes undeniable how ingrained baseball is in Japanese culture — and how different that experience is from what we know in America. These teenagers’ every swing, at-bat, chore, reprimand, lap, throw, catch, and breath is in service to success on the field. They don’t dream of becoming superstars but rather, simply, successful, a quality that resonates differently in Japan than it does in the States. It means honor for your team, school, community, and prefecture; failure brings embarrassment, shame, and, worst of all, perhaps the end of your baseball career. It can be wrenching to see them struggle to process being crushed by defeat while maintaining a stoicism they feel is expected from their coaches and teammates.

What is the value — and cost — of such totality? It’s a question playing out not just in youth baseball but across Japan as it grapples with the opportunities and hazards of adapting too fast, too much, too slowly, or not enough to the 21st century. And it’s natural for baseball to be the microcosm of this existential moment. In Japan, the sport has long been the stage for the nation to reckon with its past and future, from postwar reconstruction to the mid-century economic miracle to adapting to globalism. Yamazaki doesn’t present recommendations, but she does give us the context for the conversation.

Koshien is a beautiful film about baseball and its disciples. It’s also an entry point to better understand a nation and culture too often stereotyped by the West — and to look at our own priorities, especially when it comes to the one-time national pastime.