Are there treasures untold lying beneath the oily surface of the Gowanus canal?

An organization dedicated to the protection and preservation of historical artifacts, Archeology and Historic Resource Services (AHRS), have attempted to answer this question. In a recent report they explored the identity and history of a number of large mystery items found in a 2010 sonar scan of the Gowanus Canal.

The history of a boat, most recently called the S.S. Gay, has been outlined in previous reporting, but the other items, found in the 4th Street turning basin and 6th Street basin of the Gowanus, have foggier histories—some of which remain completely unknown.

Three of the remaining items are presently unidentified due to the depth at which they are submerged, as well as their relative size. ARHS speculates that the items could be failed parts of the canal’s retaining wall, old floating work platforms, or pieces of the other wreckages that have shifted over time. These items have been given level two monitoring, and will be watched in order to assess archaeological significance.

Two additional structures, one found in the sonar scans and one found by looking down into the canal from the bank, have been identified as small aluminum boats. They likely sank sometime after 1955, when the United States Army Corp last dredged the canal. These kinds of boats were commonly made in the 1950s and thousands remain in use today, giving the boats no historical significance.

However, there are two items that present a clearer window into the history of the Gowanus Canal: two sunken barges.

The Gowanus Canal, which was constructed on the Gowanus creek in 1850, saw heavy traffic by wooden barges between 1915-1950. These barges were brought from place to place by small tugboats and were widely used in the area to transport railroad cargo between the Port of New Jersey and the Port of New York.

In the 1960s and 1970s, wooden barges were abandoned in large numbers and left to rot. By 1964, use of the Gowanus Canal had dwindled, as more and more materials were transported by road vehicles.

For decades, a 110-foot long wooden structure has seen sticking out of the canal at low-tide. It has been identified with limited certainty as Spartan 357, a wooden barge likely built in the 1920s. This remnant of the Gowanus’ history as an important waterway has been identified as a covered barge due to its one story deck house, was used commonly in the New York area in the first half of the 20th century.

AHRS has not been able to conclusively identify the barge. However, photo documentation provides evidence that the barge had not sunk in the canal before 1974. Further research revealed that this same year, Spartan Dismantling Corporation, a company located along the canal in the 1970s, bought a wooden barge matching the description of the current wreck.

Documentation reveals that their wooden barge, called Spartan 357, sank due to damages sustained while being maneuvered around another barge in 1979. The wreck took place across from the Spartan Dismantling Corporation, placing the sunken wreck in the 6th street basin of the Gowanus Canal, at the approximate location of the wooden structure in question.

With no further information on similar wooden barges sinking in the Gowanus during this time period and in this location, AHRS has concluded that the current wreck is in fact Spartan 357.

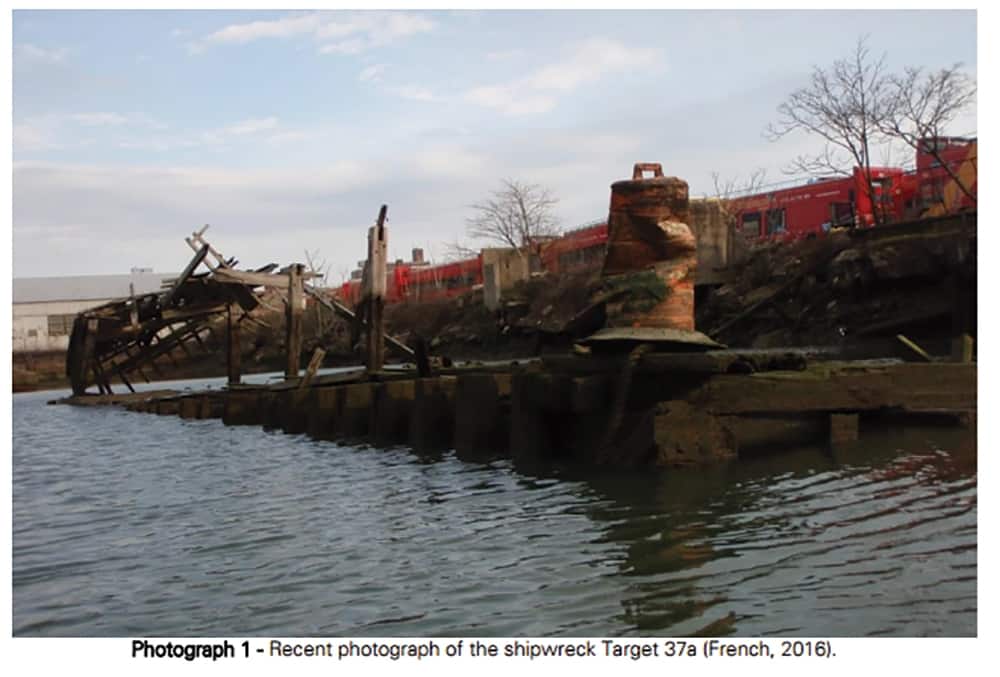

The second barge, 125-feet long and constructed of welded steel, sits further into the 6th Street basin. Its rusted metal exterior pokes well out of the water during low-tide, giving AHRS enough information to identify it as a deck scow, which were common barges throughout the New York port after World War II.

Due to the sizes of both barges, it would have been impossible to navigate this steel barge in or out of the 6th Street basin around the wreckage of the sunken Spartan 357. Trapped by the sunken wooden barge, the steel barge was presumably abandoned in the canal, AHRS concluded.

Preserved wooden covered barges and steel deck scow barges remain in existence today—both at museums and in service. Because these two specific wreckages have deteriorated over the years and better examples of these barges exist, the two Gowanus wreckages have been classified as having no historical value.

In addition to the large chronicled items, clean-up crews expect to find a variety of small trash—from tires to traffic cones. While the artifacts present in the Gowanus may not be historical treasures, they certainly present a unique window into the history of our area.

Who knows? Maybe the most interesting objects are yet to emerge from the mysterious murky waters of this local waterway.

The preliminary rounds of pulling out large debris from the Gowanus began at the end of October in the 4th Street turning basin and is expected to continue for the next month.