My oldest friend Lan comes into New York City about once a year nowadays. He’s lived in Orlando, Florida, for the past 20 years.

One night, three years ago, he insists that we go out.

“It’s late. I’m tired,” I say, feeling lame.

But it’s a cool summer night in Brooklyn. He didn’t come all the way from swamp Orlando to sit in my air conditioning.

“Let’s just go for a walk,” pleads Lan. Even though we’d been out a few nights in a row, we both know we’re going out.

What kind of friend would I be if I said no?

“Let’s go grab a beer at Bar Chord.”

“Is this some kind of hipster bar?” he asks, making a face.

Laughing, I say, “Shut up, man. You’ll like it.”

Bar Chord is a local bar on Cortelyou Road in Ditmas Park where I live. They have terrific jazz ensembles, blues bands, and acoustic acts. Sometimes I’ll go there just to have a few beers by myself and listen to the music. It’s nice to be able to pop in casually.

When we get to Bar Chord, the band is on break. I’m almost glad they’re not playing. I’m pulling myself through this.

After we order beers, the music starts up again. I don’t know who is playing, but it’s a blues group.

In just a few seconds, it’s clear that this is a great band and that the guitar player is amazing. Not just good. It’s like he’s taken off on a rocket ship with his solos. He’s playing a Bobby Bland song that I recognize. Not only can he rip the shit out of his guitar, he can sing, too.

Now I put my drink down and look over at Lan. He’s digging it.

I’m kind of stunned. This guy is just too good. He’s tearing up his guitar playing soulful blues licks, sometimes pulling on long notes with his slide. I’m getting chills. He’s dialing in guitar phrases that I’ve heard before. The bell-tones. Slide riffs, thick and slow like molasses. Like a radar signal has gone up my spine and turned my brain on highline mode.

Lan and I are shaking our heads in disbelief.

“You see,” he says. “I told you we should have gone out.” His eyes are watery.

“I know, I know,” I say. It’s like someone woke Duane Allman from the dead and put him up there on that stage. The screaming slide notes. The blues riffs packed with tears and pain.

“Now I’m going to play something from my new album,” says the guitar player, during a brief pause between songs. The drummer trots into an R&B rhythm, the band follows. The song is funky and soulful. Some people start dancing to the tune. The small crowd at Bar Chord is totally into it. Then the guitar player starts singing. He has long hair, like a real rock star. But he doesn’t just look the part. This guy can do it all.

Who the fuck is this guy?

I look his name up on my phone. I can’t believe it. It’s Scott Sharrard, musical director, co-writer and guitarist for Gregg Allman. I’m afraid to admit that I don’t know who he is. But this is beginning to make sense. Bar Chord’s a great place, but this guy is Greg Allman’s fucking guitar player! Greg Allman can have anyone as his guitar player. He’s played with some of the best electric blues guitar players of our time.

After sliding down a rollercoaster of joys and sorrows, because that’s what this music does to us, the set ends on Sharrard’s version of “Melissa” by The Allman Brothers. Motherfucker.

Lan and I are blown away. We’re not even stoned. This is simply miraculous.

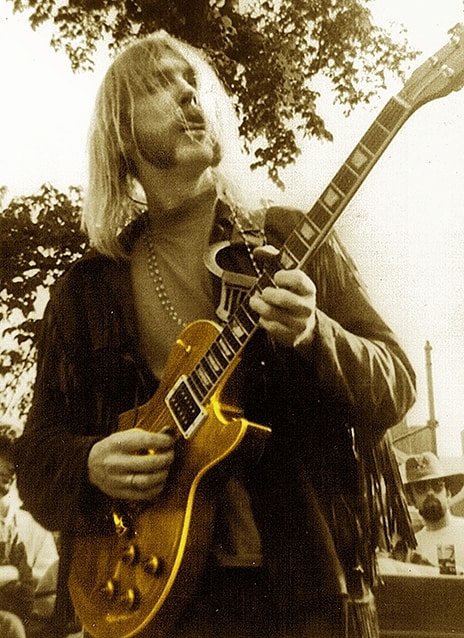

I now know that the R&B song Sharrard played is on his 2018 album, “Saving Grace.” I now know that “Saving Grace” was recorded with the Muscle Shoals music elite. And, to channel Duane Allman, Sharrard played Duane’s storied 1957 Les Paul Gold Top.

I now know that the R&B song Sharrard played is on his 2018 album, “Saving Grace.” I now know that “Saving Grace” was recorded with the Muscle Shoals music elite. And, to channel Duane Allman, Sharrard played Duane’s storied 1957 Les Paul Gold Top.

“Saving Grace” also features “My Only True Friend,” which was co-written with Gregg Allman. It is Gregg’s last known original song, originally planned for Allman’s Southern Blood album. Allman’s health prevented him from recording it. Their song now lives in Sharrard. In fact, so much of The Allman Brothers lives in Sharrard.

Sharrard’s playing calls to mind the first time Lan’s brother, Lester, plays Eat A Peach for us. Stereo on full volume, making every organ in my body shudder, Lester talks about how much he loves this album. Though at that time he was a born-again Christian, Lester tells us that The Allman Brothers had to be listened to while tripping on acid to get the full impact. He doesn’t realize it, but I hear him saying you need to do acid and listen to this record now.

Because he’s passionate about the music and the myths surrounding the music, Lester essentially establishes our musical taste. And because we venerate the ground he walks on, we listen to his favorite records, trying to hear them like he hears them.

Years later, when our friend Paul and I listen to Mountain Jam on LSD, in fulfillment of Lester’s prescription, our minds become one. We become eternal. This music speaks to you about the history of the cosmos, about love, and friendship.

In 2001, Paul is taken from us in the World Trade Center tragedy.

Then, a few years later, we lose Lester to a sudden stroke.

As Sharrard is playing, Lan and I share a space where Lester and Paul continue to exist. They are in the music, in the notes.

Crossroads, will you ever let him go? The gypsy flies from coast to coast.

It dawns on me that Paul was always the gypsy of that song; that while he lives in an infinite blue sky, the rest of us are growing old and gray. That we would never let him go and yet he must forever fly away.

The joke is on us, as usual.

And Sharrard’s music, his playing, his singing, is bound up with all of this. He knows what he’s doing. That, as he leans forward, incorporating new styles into the blues, his music is brimming with the past.

The song “My Only True Friend” is written from the perspective of Duane Allman, as if Duane had written it for Greg. I realize why I had been so moved that night by Sharrard’s playing. He embodies the spirit and the abiding love that brothers have for each other.

I hope you’re haunted by the music of my soul

When I’m gone

Please don’t fly away and find you a new love

I can’t face living this life alone

I can’t bear to think this might be the end

But you and I both know the road is my only true friend

As Lan and I head home, we are shocked into silence. Lester and Paul’s spirits are there with us. To say, hey, remember when we listened to this music. People can you feel it, love is everywhere.

The love that keeps you going on this road we call life.

The love of true friends.