Cindi Mayweather succumbs to pleasure. Anyone who caught Janelle Monáe’s 2018 concert in Prospect Park (and reportedly thousands didn’t and were turned away once the bandshell grounds were filled to capacity) knows what a dynamic performer she is. She seriously enjoyed herself, putting on a tight show, copping moves from James Brown and Michael Jackson and gleefully admitting defeat in an audience challenge dance-off. And those who bore witness to her opening for Prince at Madison Square Garden in 2010 know Monáe is too cool to touch. (“She’s so bad she don’t pronounce the ‘n’ in my name,” the master told the audience that night). She’s also got bonafide acting chops, as demonstrated, for example, in Moonlight and Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery. And in the wake of the release of The Age of Pleasure (CD, LP and download co-released on her own Wondaland with Bad Boy and Atlantic), she’s presumably still got a killer record gestating inside her.

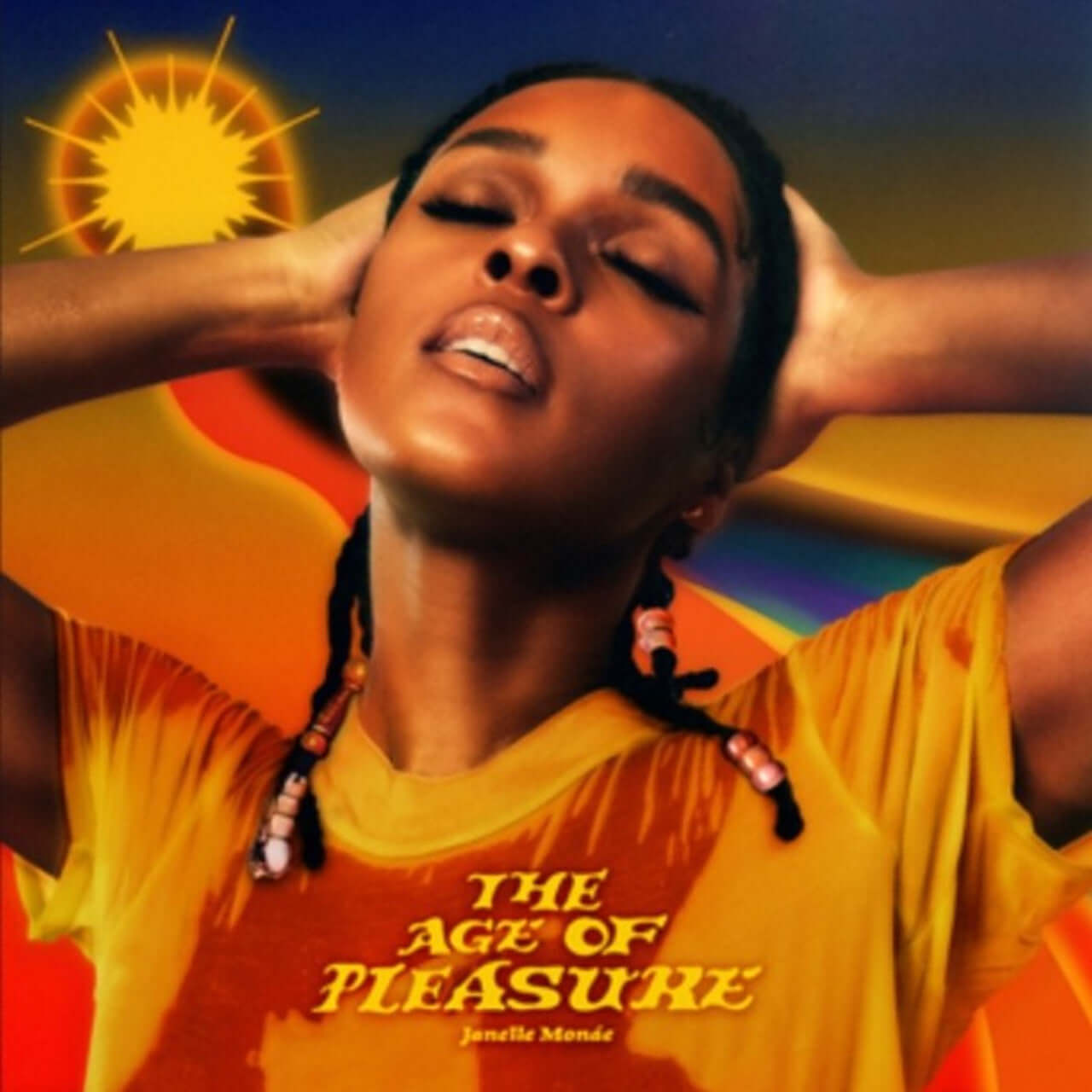

Back in 2018, Monáe discussed the possibility of a movie exploring the story of Cindi Mayweather, an android character woven through several of her albums. Naturally, she would do the music as well. “I want my Star Wars,” she told the magazine. “As a writer, as a storyteller, as an actor, to be able to do the soundtrack that’s rooted from works that I wrote.” That would (will) be the killer record she’s capable of. The Age of Pleasure, on the other hand, might be that not-yet-born album’s polar opposite. It’s also a very good record, light and uplifting with unapologetically fluid lyrics (she addresses female lovers with passion and lust, and without politics) and complex, layered funk. It might be her lightest record to date, but that doesn’t mean it’s shallow.

Ms. Monáe is probably right. The world needs to delight in nonjudgmental bodily pleasure right now much more than it needs a multimedia dystopic, electrified opera. But the quick disc doesn’t quite scream indulgence; the 14 tracks fly by in just 32 minutes, with only two breaking the three-minute mark. That’s the real shame of The Age of Pleasure. There are plenty of tunes that deserve six minutes or more of movement and groovement but don’t get it. The lead single and first track, “Float,” is one of those two (at a whopping 4:02). On it, she sets an m.o. for the album: I don’t step, I don’t walk, I don’t dance, I just float.” It’s also one of two songs featuring Seun Kuti and Egypt 80, which are the best tracks on the album. The horns will make you thirst for more.

To really submerge in those horns, you’ve got to go to the source. The Brooklyn-based Partisan Records (a part of Knitting Factory Entertainment) just released a 50th anniversary vinyl pressing of Seun’s father Fela Kuti’s Gentleman, a turning point in the discography of the Afropop architect. In the 14-minute title track, Kuti announces in pidgin English that “I no be gentleman at all,” an understated warning for the more political records he would soon be releasing, looking European colonialism in Africa direct in the eyes. The two tracks on the flip address surviving heartbreak (“Fefe Naa Efe”) and staying loyal to friends (“Igbe”), the points made as always through repetition in multiple languages and over hypnotizing, funky music. It’s not Fela’s best record, but Partisan is working through the catalog (having already issued them on CD back in 2010), which means things are about to get really good.

More bad-time party jams. Just in time for the dog days of another summer of discontent, Marc Ribot’s Ceramic Dog is back with more new anthems for a world in decline. Beholden-to-no-one guitarist, songwriter and rabble rouser Ribot speaks truth to the powerless in a way not so dissimilar to Fela’s proselytizing, although his roots are more in punk attitude and r’n’b guitar. The opening title track on Connection (CD, LP and download out on Bastille Day from Knockwurst Records) almost sounds like an answer song to the Rolling Stones 1967 song of the same name, with Ribot taking on Mick Jagger’s mawkish bluesman vocals, at least until the synth noise and blistering guitar solo kick in. But where Jagger can’t make no connection, Ribot is watching someone simply missing it while trying to muscle their way through another day. The band is hot as a city sidewalk in the July, with a crew of guests on different tracks, Anthony Coleman and Greg Lewis on organs and James Brandon Lewis and Oscar Noriega on reeds among them, rounding out the solid guitar trio of Ribot, drummer Ches Smith and the invaluable Shazad Ismaily on bass and electronics. Some deep groove instrumentals give them room to strut. Come for the societal breakdown, stay for the rendition of “That’s Entertainment.”

And while on the downtown guitar tip, NYC mainstay and six-string polymath Elliott Sharp posted a name-your-price tribute to the late Jeff Beck to his Bandcamp page that’s well worth five minutes of your time. And while you’re there, check out the recent, remixed, remastered, 25-track collection of tracks by his Terraplane, with the great blues guitarist Hubert Sumlin on several cuts.

Blind Joe Death Resurrects Anew. It’s easy to miss five or six decades hence how radical John Fahey’s early records were. Non-programmatic folk-style fingerpicking just wasn’t a thing when his first self-released albums (sometimes using the name “Blind Joe Death” appeared). On the other hand, Fahey’s musique concrète tape collages still sound about as out of this world as ever. Fahey remained a contentious figure right up to his death in 2001 at the age of 61. He started performing on electric guitar fairly late in life, which added new atmospherics to his already nebulous, blue-based inventions. Rather remarkably, a new set of late recordings has been unearthed and polished up for release by Drag City under the title Proofs and Refutations. The set of eight tracks, totalling 45 minutes, begins with a preacher-styled recitation with heavy reverb and lots of repetition. It’s fairly hilarious, but it also shows his deep fascination with sound, be it his voice, his guitar or recordings of trains. The tracks were laid down in a room in a Salem, Oregon, boardinghouse in 1995 and 1996 and whatever gear he was using at the time, the audio is remarkably clean. What’s fascinating here, though, is the sense of Fahey listening. He was a stunning guitarist, but here he’s alone, more interested in the sounds of his instrument (both acoustic and amplified) than his aptitude on it. He locks into phrases and figures, then abandons them for thumps, buzzes and single-note fixations. The album (LP and download) isn’t out until Sept. 8, but you can ease the wait by making tracks to Picture Theory in Greenpoint, where a show of Fahey’s paintings is up until August 12, by appointment only. Go to picturetheoryprojects.com to make a reservation.