Werner Herzog, the German filmmaker and Baby Yoda enthusiast, doesn’t much like chickens. In his view, chickens embody “a kind of bottomless stupidity, a fiendish stupidity. They are the most horrifying, cannibalistic, nightmarish creatures in the world.” Mr. Herzog is not alone in this estimation.

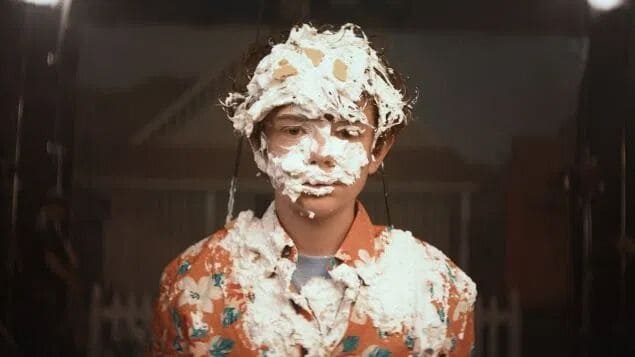

Showmen and grifters train these birds to dance, play checkers, and perform tricks not because of their unique cleverness, but because chickens are performers. Creatures of unvarnished externality, they lack internal thoughts and complexities, and instead allow their behavior to be molded by those around them. In the new autobiographical drama Honey Boy, Shia LaBeouf portrays himself as a trained chicken and asks whether he can ever become something more.

Written by LaBeouf during a court-ordered stint in alcohol rehab, Honey Boy follows Otis, troubled star of the Not-Transformer films, as he reflects on his childhood and the abusive father who shaped him.

Otis, it seems, had a profoundly troubled childhood. Twelve years old and already an established television star, he lives in a run-down motel with his father, James, a chicken tamer-turned-circus clown bursting with uncontained insecurity and violence. Early in the film, their relationship alternates between affection and abuse; the pair practice juggling and line readings, but James also belittles and beats his son.

James and his contradictions lie at the heart of Otis’ pain. James’ instills in his son a strict work ethic and encourages self-sufficiency, but also enables the boy’s most self-destructive habits. Later in the film, LaBeouf reveals that Otis employs his father as his on-set caretaker. James’s paternal kindness is transactional, but he chooses to be cruel.

Complicating this basic structure is LaBeouf performance as James, the fictionalized version of his own abuser. LaBeouf plays his father as all swaggering id, a shameless flirt who externalizes his personal humiliations in public meltdowns. Yet for all his faults, LaBeouf infuses his performance with warmth. LaBeouf’s abuser was not a faceless monster, he was a father who tortured his son because he could not escape the consequences of his own self-inflicted injuries.

This all makes Honey Boy a fascinating exercise in exposure therapy. But does the film function beyond its star’s metanarrative? The answer, unfortunately, is mostly no.

Director Alma Ha’rel does what she can. An ingenious early montage reveals how Otis’ on-screen antics, a blur of sex and substance abuse and casual violence, bleeds into his personal life. Later, she depicts the young Otis’ one true moment of interpersonal connection not by staging a heart-to-heart conversation, but through mime. Lit by Ha’rel’s warm reds and purples, Otis performs for the first time not as his father’s trained bird, but as a boy in dire need of emotional expression.

Lucas Hedges does not help. Playing the adult Otis, Hedges’ hyper-specific performance undermines any possibility of a larger narrative. Rather than creating an original character, Hedges apes LaBeouf’s accent and mannerisms too closely. His Otis/LaBeouf cannot modulate any act or emotion, and the resulting physical performance feels more like caricature than characterization. Hedges aims at a total transformation, but falls somewhere between an SNL impersonation and the uncanny valley.

Additionally, LaBeouf and Ha’rel’s falter in their depiction of ongoing emotional pain. Near the end of the film, Otis tells his therapist that he channels his childhood traumas into his performances. So long as Otis/LaBeouf make films, they must revisit his most difficult memories, and cannot truly find closure. Honey Boy‘s very existence, therefore, undercuts its sweet and optimistic denouement.

Life is more complex than narrative allows. The specificity of LaBeouf’s paternal traumas could never fully translate to a commercial film. Nevertheless, LaBeouf exposed himself, his biography, and his healing process to public scrutiny. Honey Boy is a bold, courageous film, one that I hope does not derail his healing process.

3/4 Stars

Honey Boy is currently playing at the Angelika Film Center, Village East Cinema, and Williamsburg Cinemas.

Author

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.