The Lehigh Valley Barge #79 was built in 1914, and celebrated her 100th birthday last year. She is the last of her kind.

The barge was built entirely of long-leaf yellow pine, or Pinus Palustris. Boards cut from these trees are very heavy and will not rot, making them extremely suitable for shipbuilding.

The trees mature after 100 to 150 years and may live to be 500 years old. Vast forests of the species were once present along the southeastern Atlantic coast and Gulf Coast of the United States.

The long-leaf pine forests were sourced by merchants and the navy to build ships, like the Lehigh Valley #79. Due to deforestation and over-harvesting, only about 3% of original long-leaf pine forests remain, and very few are replanted. Modern shipbuilders began using steel.

The company that built #79 originated out of Lehigh Navigation Company. The company was one of 13 major railroad companies in the Northeastern U.S. around the turn of the 20th century. The NY Harbor was the biggest seaport in the world. By connecting railway to barges, the company was able to intersect land and water, railway to barging.

During that time, the Lehigh Valley Railroad Barge #79 was one of thousands carrying cargo through the New York Harbor. As the shipping industry modernized, and bridges and tunnels were built, these barges became obsolete. Most were left to ruin; as of today, #79, David Sharps floating Waterfront Museum, is the only surviving wooden barge.

The Lehigh Valley Navigation Company built sturdy canal barges with a bulkhead in the center and cross-bracing frames. The barges were built to last. Other companies had no experience building barges, building less durable “matchbox” vessels. Sharps credits #79’s design for her survival.

Despite her strapping, well-made frame, the barge is struggling a different battle. Boats play a game with Mother Nature and Father Time.

Natural elements deteriorate the barge on a daily basis. Rainwater, snow, ice, sunlight, flotsam and other elements compromise the integrity of the vessel. Other things bumping into the boat also cause damage. “Rock, paper, scissors – shoot!” Sharps says. “That game of steel, concrete, motion, wood seems to always leave wood the loser.”

The barge is made of thousands of pieces of wood and thousands of seams. While saltwater beneath the boat doesn’t harm the wood, the fresh water can have immense effects. One droplet of water can make its way through the cracks and create a hole in the barge. “All disaster need is a toe in the door – opportunity.” Sharps explained.

Another major concern to the barge is parasitic creatures that eat their way into the wood just below the surface of the water, turning the underside of a wooden boat into Swiss cheese. . There are two main types. The shipworms – or teredo – are actually mollusks. They can grow up to five feet long and nestle themselves into the wood, devouring planks of wood throughout their lives.

The second threat are gribble worms, crustaceans that are about the size of a grain of rice. These creatures are very mobile and can move forward and backwards, jump and swim. The wood provides them with both nourishment and shelter. They eat out holes in the wood just under the surface of the water. Hoards of the gribbles can break off exterior layers on the ship, and dive right back in to the next layer to begin the process anew.

Despite outward appearances of the wood being intact, repeated molestation of the planks can cause severe damage to the structural integrity.

In 2002, Sharps was wrestling with the infestation of both of these pests. During dry-dock repairs, that year, he discovered that nearly half of the wood below the waterline had been eaten away. The worms were blasted out with pressure washing. Vulnerable wood was ripped out, and replaced with long-leaf yellow pine from the bottom of the barge to 18 inches above the waterline. The fresh wood was treated with asphalt primer and roofing cement, twelve inch wide wooden strips covered all seams, and then was treated again. Finally, the area was sheathed in a plastic material.

Thirteen years later, Sharps is going back to dry-dock to find out if the shipworms and gribbles were able to find a way inside. He’ll also be looking for Mother Nature’s mark of deterioration. All of this, on top of the accelerated effects of damage caused during Hurricane Sandy will have to be repaired.

Sharps described the barge’s encounter with Sandy:

During the extreme height of the two incoming tidal surges, the vessel moved both past and above its normal rubber fender system thus damaging sacrificial wooden rubbing timbers. Ropes were slacked to accommodate the 13 foot storm surge which further accentuated the jostling and violent movement of the boat.

The river was filled with flotsam and jetsam that included dozens of dangerous 30’ wooden poles that churned in the waters causing excess abrasion damage to the hull, especially around the vulnerable corners.

The first high tide rose into the street equaling the height of Hurricane Irene the previous year. At this point the superstorm’s level of water never subsided. The river refused to ebb. Over the course of four successive tides and lasting close to 24 hours, crew with life jackets donned continually slackened lines to the west to allow for the barge to rise and tightened lines to the east in an effort to keep us from continually grinding into the dock.

At one point as the barge was rising like Noah’s ark…

Delicate is the dance between Sharps and Mother Nature. Father Time plays his part in the competition. But the Lehigh Valley Barge #79, the lone survivor aims to be around in another hundred years.

Because he is listed with the National Registry of Historic Ships, he is required to replace like-wood with like-wood. But since the long-leaf yellow pine forests have been depleted, the wood can no longer be obtained. Sharps will be using plastic lumber as “fender timbers” for bumpers to protect the exterior of the barge.

Depending on the damage uncovered by the inspection, Sharps says, “I need to make the best decisions I can.” But he won’t know until the barge is dry-docked.

The cost of these repairs is estimated to be approximately $192,000. To date, only $45,000 has been raised. The 2nd Annual Pirate’s Ball on May 15 will help finance the repairs and 70 hour roundtrip. The event will feature a sunset cocktail hour, live music, local food, and even an opportunity to walk the plank. Tickets and more information are available at www.barge100.org , the Waterfront Museum, or by calling (718) 624-4719.

Over the last three decades, public and private funds have been dedicated toward restoring and revitalizing these 520 miles of the NYC shoreline, offering city dwellers opportunities to engage directly with sky, water, and wildlife.

While parks and piers are the most common spaces that allow people to get close to the water, there are very few public places where one can actually be on it. The Waterfront Museum is one such exception.

In a 2004 article in New York State Conservationist, Brian Swinn wrote, “And so it goes. Man, his works, and Nature inextricably linked in an endless cycle across time.”

3 Comments

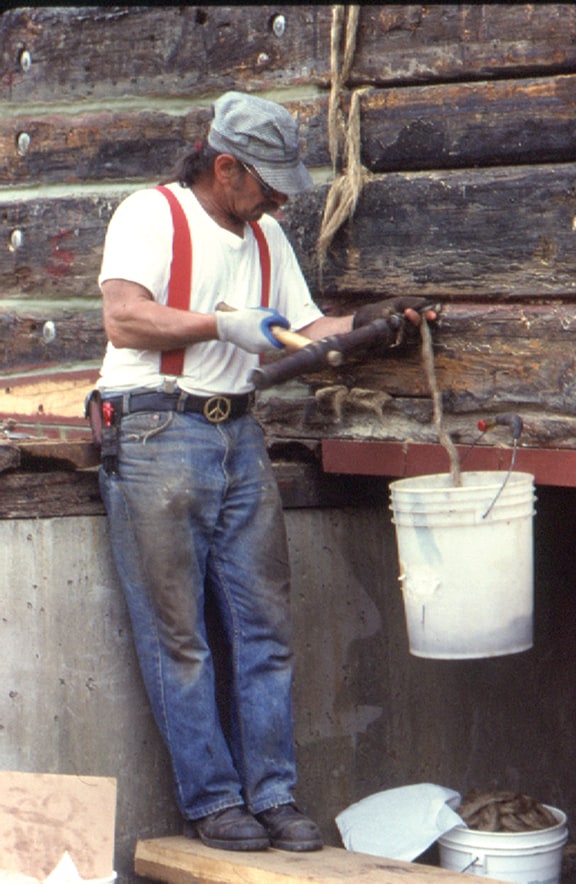

The caption under the photo begins, “A worker . . .” The worker’s nme is Don Taube, quite a well-known mariner, craftsman and personage in the harbor at one time. https://tugster.wordpress.com/2007/07/10/loss/

That is my dad in the picture, Don Taube as Will said. He passed away in July 0f 2007, leaving us too soon. It would be amazing if you could re-label the picture caption. He was incredibly talented and loved what he did – he especially loved teaching others. He was a master blacksmith, welder, caulker, captain – an all around shipwright.

Thanks for updating the caption, so appreciated. He still lives in our memories – and these wonderful photos.