“I came here to raise badass, obstreperous, antisocial, pestiferous, brutalitarian, loudmouthed and chaotic bloody hell. The roaring kind!”

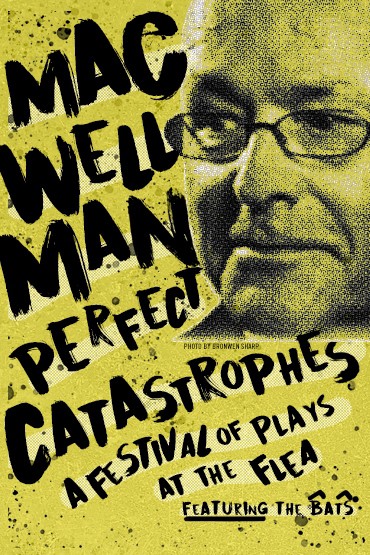

]In playwright Mac Wellman’s Sincerity Forever, a celestial visitor to a hamlet of reverent, well-meaning hillbillies announces her presence by the declaration above, but it might also serve as the motto of the artist himself. Wellman – a major figure in New York’s downtown theater scene, a CUNY Distinguished Professor at Brooklyn College, and the recipient of the Village Voice’s 2003 Obie Award for Lifetime Achievement – co-founded the Flea Theater in Lower Manhattan in 1996, and this fall, a festival of five of his plays, written between 1989 and 2005, will take place on his home turf. The Flea’s Perfect Catastrophes, which started August 24, offers new interpretations of Wellman’s puckish, peculiar work, some of it previously unproduced.

Two one-hour comedies, Sincerity Forever and Bad Penny, which theatergoers can watch in a single evening with a break in between, have already begun their run; The Invention of Tragedy will join them in repertory on September 7. In 2017, the Flea, known for its experimental fare, moved into a new state-of-the-art facility in pricy Tribeca, which it owns, but its young actors still sometimes serve double-duty as ushers or box office attendants.

In Bad Penny, a man self-identifies as “a freelance memory fabulist and metaphysician and card player.” Again, the character could be speaking for the whimsical but cagey author: Wellman’s not a normal playwright. Over the years, he has pioneered a dramaturgy that rejects characterization based on rational psychology, which, on Broadway, tends to frame the world and its inhabitants within neat, satisfying, and even normalizing theatrical explications.

A political malcontent and proud crank, Wellman finds his rebellion in a refusal to naturalize the madness of modern life, which his work channels with ironic good cheer into surprisingly entertaining heaps of eloquent gibberish. With fractured stereotypes and brain-melted refugees from TV commercials and soap operas populating his plays, Wellman takes the focus off the ever-dignified individual and finds a dramatic form for the brokenness of our culture. His plays can be difficult to read, but on stage they’re vibrant small-scale spectacles.

Performed in a 46-seat basement, the smallest of the Flea’s three spaces, Sincerity Forever takes the shape of a teen drama, set in southern Appalachia, where curious, tenderhearted high-schoolers fall in love, quarrel with their friends, and ponder the meaning of life. And they do it all while wearing Klansman robes.

Performed in a 46-seat basement, the smallest of the Flea’s three spaces, Sincerity Forever takes the shape of a teen drama, set in southern Appalachia, where curious, tenderhearted high-schoolers fall in love, quarrel with their friends, and ponder the meaning of life. And they do it all while wearing Klansman robes.

Their hometown – Hillsbottom, USA – is a place where no one knows anything about geography, government, economics, or any other subject, and that’s the way residents like it. In the absence of facts, they have faith and innocence and sincerity. They may not know why they believe what they believe, but they make up for it by believing it all the more wholeheartedly – until, that is, an invasion of alien “furballs,” in the style of pissed-off crust punks, poisons them with self-doubt, confusion, and rage.

Something in me reflexively bristles when I encounter a Southern accent on a New York stage. I can feel the condescension in the room. The meta-rednecks of Hillsbottom aren’t supposed to represent “real” rednecks, but their beloved Christian Lord and Savior – who, embodied as a black woman, employs a diction that, purposely or not, contains an unmistakable echo of minstrelsy – does show up to condemn their anti-Semitism and homophobia.

But thanks to Wellman’s sharp sense of absurdity and prodigious gift for language, this material doesn’t register primarily as a liberal New Yorker’s harangue. His characters, parodies of themselves, speak their pious stupidity with Shakespearean flourish and originality – and then fall face-first into dunderheaded banality and cliché. The mixture is hilarious and exhilarating. Their philosophies may be awful, but their philosophizing certainly leaves an impression.

When the weather holds up, the Flea stages Bad Penny, the second play of the night, in the building’s AstroTurf backyard. Wellman originally wrote it as a site-specific piece for Central Park. Playgoers can sit wherever they’d like, choosing among lawn chairs, a bench, a picnic table, and a yoga mat. The actors insinuate themselves into the outdoor hangout casually and then work around the audience.

The players – comprised, as in Sincerity Forever, of the Flea’s energetic resident ensemble, the Bats – adjust seamlessly to the placement of the crowd. On a perfect-weather Sunday, I didn’t realize that the woman next to me was a performer until midway through the show, when she started chanting satanic incantations.

Bad Penny tells the story of a motorist from Montana who gets a flat tire on the Upper East Side and tries to cross the park on foot to find a gas station. He meets a strange young woman who has picked up an unlucky penny and now expects a visit from the Boatman of Bow Bridge, a legendary troll that menaces Central Park. The man doesn’t believe in trolls. Various other parkgoers insert themselves into the man and woman’s debate.

“People come to the lunacy of places like parks to escape the even more terrible lunacy of their lives in the city, lives lived without love in many cases, lives of terrible, meaningless work, lives of torment, addictions to strange and disgusting substances, lives devoted to insane passions, obscenity piled upon obscenity, lives rendered unendurable by long incurable wasting diseases,” Wellman writes.

His cast of eccentrics, put-upon everymen, and wised-up toughs tries to believe in logic, progress, consumerism, and the goodness of the universe in order to keep all this horror at bay, but none of it works. The Boatman is coming.

Though a considerable poet, Wellman isn’t too precious with his words. His goal is to create an effect upon the audience – a sensation of excitement, not necessarily of comprehension – and his characters often talk on top of one another, rendering half their speech unintelligible. Clearer moments might make use of a phrase from an advertising jingle or a sublime formulation of Wellman’s own. Bad Penny is fantasy and artifice, but it authentically captures some of the noisy, irritating vitality of public spaces.

Mac Wellman is now 74 years old. The plays of Perfect Catastrophes provide a summation of an admirable career of mischief, obliqueness, fury, and merriment. Since their initial publication, some of Wellman’s proteges, like Young Jean Lee and Annie Baker, have come into their own as significant theater artists, but even more of his enemies – the earnest authors of stale, realistic drama – have prospered.

Concluding with The Sandalwood Box and The Fez, the festival ends November 1. Purchased in advance at theflea.org, tickets can cost as little as $15, and last-minute student rushes go for $10 in person at 20 Thomas Street (212-226-0051).