This month’s name comes from Janus, the two-faced god, looking forward and backward. A crossroads on the calendar, in other words, and here we are again at a crossroads that I’m sure most of us wish we could leave behind.

Where is jazz in January? As December began, I was organizing this month around the return of the NYC Winter Jazzfest 2022, one of the best and most comprehensive jazz festivals on the planet. Writing this now a few days before the end of the year, I’m waiting to hear what events mights end up streaming, as all in-person performances have been postponed due to another spike in COVID infections.

So we watch and wait, again, more. Hopefully, Carnegie Hall will be able to present their Afrofuturism Festival in fall. The opening event is February 3, and Carnegie is going ahead with their January schedule, so fingers are crossed. The festival has a central core of jazz, including the Sun Ra Arkestra in Zankel Hall on February 17, because Sun Ra is the recognizable originator of Afrofuturism as both philosophy and aesthetic. The idea never strays far from jazz, which means in concert you’ll be able to hear Nicole Mitchell and Angel Bat Dawid, and Theo Croker, and also Flying Lotus and the Carl Craig Synthesizer Ensemble. You can find the complete schedule of events at https://www.carnegiehall.org/Events/Highlights/Afrofuturism.

Looking back, 2021 was a great year for jazz on record, with some new recordings that promise to become bona fide, long term classics, and archival releases that mixed historical importance and artistic quality. For the former, I absolutely recommend Vincent Herring’s Preaching to the Choir (Smoke Sessions) and James Brandon Lewis’ Jesup Wagon (Tao Forms). Lewis put out three album last year, not including his membership in Irreversible Entanglements, and each is superb.

From the archives, in these pages I’ve already covered great recordings from Miles Davis, Joe Henderson, and Julius Hemphill. Blank Forms released two essential Don Cherry recordings, along with a book, that fill in the gap between his free-jazz period and his transformation into a global griot, via his life in Sweden with his wife Moki. These are incredibly important documents and the music is absolutely fantastic.

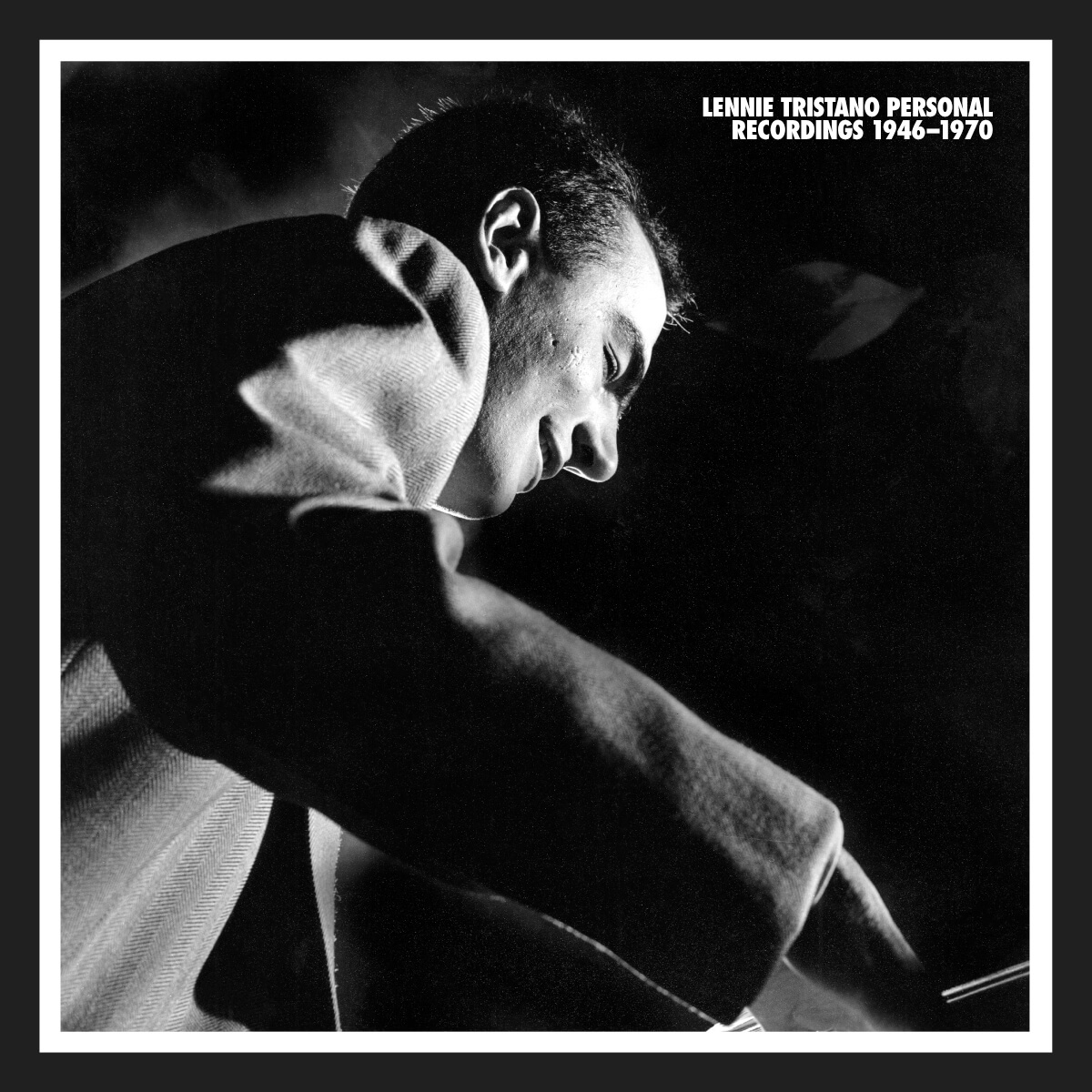

Coming in too late for year end polls was Lennie Tristano Personal Recordings 1946-1970, a 6-CD set produced by Mosaic Records, in collaboration with Dot Time Records, that is now available at mosaicrecords.com (Dot Time put out another Tristano archival release, The Duo Sessions, in 2020). The title says it all: this is the personal tape collection of the great pianist and teacher. The bulk of this music has never been heard by the public before, although those lucky enough to have the amazing Carnegie Hall X-Mas ’49 CD previously issued (and out of print) on the Jass Records label will know the scintillating live “You Go To My Head” and “Sax of a Kind” with the sextet of Tristano, alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, tenor player Warne Marsh, guitarist Billy Bauer, Arnold Fishkin on bass, and drummer Jeff Morton.

There is another half-dozen tracks from that group, recorded at Tristano’s studio in his house on Palo Alto Street in Hollis. That’s also the site for some fascinating solo pianism, with Tristano pushing his highly horizontal, contrapuntal style to the limit, and also banging out sequences of chords in an exploratory, improvisational style. It may seem redundant to use the word improvisation with a jazz pianist who was an early pioneer of free playing with a harmonic and rhythmic foundation, but that matters here, as Tristano is clearly experimenting with stacking notes together (unusual for him) and seeing what he might find within them—his piano is out of tune too, and he may be figuring out how to listen through that.

There is immense value in simply having this material together in one easily accessible package. The Tristano discography is scattered to begin with, with issues, reissues, compilations and the like in all formats going in and out of print through the decades. In late December, a quick check at discogs.com showed 85 separate items in the catalogue, and a search at importcds.com (I recommend against using Amazon, not only to not send money to Jeff Bezos but because their own search engine is incompetent and Amazon has a ridiculously bad track record even delivering CDs) turned up less then two dozen CDs and LPs as in print and in stock. Several of those were issued under Konitz or Marsh, his two most famous students/sidemen, and on a track-by-track basis there’s substantial overlap across all the releases that include Tristano.

Mosaic has previously issued another 6-CD set, The Complete Atlantic Recordings of Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz & Warne Marsh, the single finest Tristano compilation, but one that is also now out of print. Any chance to listen to his playing across more than one CD and situation quickly reinforces what a fabulous pianist he was. Even at the fastest tempos, he was always clear and coherent—making things up on the spot, he could always hear where he was going. His ability to articulate notes, to alter dynamics and attack from each to each while working through a line, was virtuosic and always in service of artistry, expression, and swing. He played like a horn player, which didn’t mean just a monophonic line, but making the piano keys sound like they were being shaped with breath, embouchure, and the like.

There are revelations here, the kind of things that reinforce the reputation of this great artist. Trio recordings with bass player Peter Ind and drummers Tom Wayburn and Al Levitt are among the best in his discography. Put down at a recording studio in the mid-’50s, they are in great sound and feature one swinging, satisfying performance after another. The home recordings, solo and with bassist Sonny Dallas, have a loose playfulness to them that show a different side to the pianist. Often criticized for being cold, Tristano was instead serious, meaning what he said and playing what he meant, utterly committed to jazz, with fire, in a way that might be off-putting to a listener who feels entitled to mere entertainment.

The CD bookends cover Tristano’s experimental side. These tracks have the roughest sound, coming from scattered sessions that include White’s Restaurant in Freeport, Long Island and Tristano’s house in Flushing. These feature the leader with musicians like Konitz, Bauer, and Dallas, and are full of beautiful mistakes. What I mean by that is, the musicians are improvising freely, making it up on the spot out of nothing within a general framework of organized rhythm and grounded in tonality. They are finding their way to not just playing together in time but making coherent individual lines and harmonies that fit together and complement each other. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t quite, and Tristano’s own taste for taking a regular four or eight-bar phrase and extending the line for a few extra beats, which is marvelous, often leaves the others behind.

But the point of this playing, and the meaning of the home recordings, is that these weren’t sessions designed to fit a dozen tracks, standards and originals, into neat segments on two sides of an LP. These were musicians looking for a new way of doing things, pressing the edges of what they themselves felt possible into the space where discoveries are made. Many listeners and writers these past couple of years have used the word “experimental” to describe all sorts of genre-based music that might play with the rules a little but, meaning it’s not actually experimental. Like in science, experimental means trying things without knowing exactly what you’re going to discover, and that’s what Tristano and his colleagues were doing, those many years back, in his house in Queens.

Looking Forward, Looking Back, by George Grella

READ OUR FULL PRINT EDITION

Our Sister Publication

a word from our sponsors!

Latest Media Guide!

Where to find the Star-Revue

How many have visited our site?

Social Media

Most Popular

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Related Posts

Special birthday issue – information for advertisers

Author George Fiala George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and

PS 15’s ACES program a boon for students with special needs, by Laryn Kuchta

At P.S. 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, staff are reshaping the way elementary schoolers learn educationally and socially. They’ve put special emphasis on programs for students with intellectual disabilities and students who are learning or want to learn a second language, making sure those students have the same advantages and interactions any other child would. P.S. 15’s ACES

Big donors taking an interest in our City Council races

The New York City Council primary is less than three months away, and as campaigns are picking up steam, so are donations. In districts 38 and 39 in South Brooklyn, Incumbents Alexa Avilés (District 38) and Shahana Hanif (District 39) are being challenged by two moderate Democrats, and as we reported last month, big money is making its way into

Wraptor celebrates the start of spring

Red Hook’s Wraptor Restaurant, located at 358 Columbia St., marked the start of spring on March 30. Despite cool weather in the low 50s, more than 50 people showed up to enjoy the festivities. “We wanted to do something nice for everyone and celebrate the start of the spring so we got the permits to have everyone out in front,”