Human trafficking is the criminal practice of buying and selling coerced or kidnapped individuals for the purpose of sexual slavery, involuntary labor, child soldiery, or another form of exploitation. Audrey Moore, CEO of Lift Up the Vulnerable (LUV), is committed to fighting against human trafficking.

Moore’s discovery of the human trafficking market began in the early 2000s as a recent college graduate working in a children’s home in Portugal. What Moore found was a lawless world where women, men, and children are enslaved in and out of plain sight. Today, Moore is focused on ending human trafficking in areas where people are most vulnerable, as well as shedding light on what the human trafficking world looks like.

Originally from New Jersey, Audrey Moore would go on to obtain a degree in education from the University of Delaware. In 2001, her interests in international affairs and travel led her to Belgium, working with a pastor and international students. Soon, Moore found her way to the Iberian Peninsula, where she connected with a couple that assisted orphans – or so they claimed.

During our interview in Manhattan, Audrey recounted what she experienced during those years and discussed what the public needs to know about human trafficking.

Roderick: What can you tell me about the orphanage in Portugal?

Audrey: I worked with an orphanage in Portugal via an organization called Make Way Partners. Most of the children were of African descent, either children of refugees or refugees themselves. These kids were in the foster care system.

At the orphanage, I met a young boy named Carlos. He was the child of a Portuguese father and an African mother. His mother was a sex worker, and his father was completely absent.

Roderick: That’s hard to hear. What do you remember about Carlos?

Audrey: Carlos was a sweet young child, I was so fond of him. He really opened up to the staff. However, the kids seemed to be directed to not speak to us very much – they seemed reluctant to open up. Carlos was a bit more talkative.

One day, Carlos kept asking for sal, or salt, I didn’t know why. I asked him, “Why do you need it, Carlos?” Then I saw the bruises.

Roderick: Was he being abused?

Audrey: Yes, he was being abused sexually. I immediately got in contact with local authorities. That’s when we discovered the orphanage was really a front for a child sex trafficking operation.

We hired legal help, but it was difficult to stop the operation. From a legal perspective, these children were not citizens of Portugal; they were refugees.

Roderick: What was the reaction from the authorities, and others?

Audrey: To be honest, things were quiet. I sensed that the authorities were kind of apathetic. Their hands were tied. We began to understand how human trafficking affects orphans and vulnerable people in general. I was in shock.

Roderick: What shocked you the most?

Audrey: Everything. We were uncovering the complexities of the human trafficking global market. Here are children being sexually exploited and we can’t just rescue them. It took us two years to shut down that orphanage.

Roderick: What did you learn?

Audrey: I learned how human trafficking manifests itself in places that have civil unrest, how vulnerabilities are taken advantage of. Human trafficking is a global operation. It manifests itself in the US as well.

Roderick: Is there a profile of a person, or people who engage in human trafficking and enslavement?

Audrey: That’s the thing, there isn’t a profile. It’s youth ministers, business leaders, politicians… anyone.

Roderick: Is there a type of trafficking that is most common?

Audrey: There aren’t concrete numbers, but we believe labor trafficking and enslavement is actually the most common type of trafficking. However, sex trafficking is obviously very prevalent.

Vulnerabilities show up in so many ways. Human trafficking is very psychological. Predators prey on isolated people, they look for them.

Roderick: If there isn’t really a predator profile, how do we protect vulnerable people?

Audrey: First, by being aware that there is a problem. Second, look out for the people in your communities, the kid that doesn’t say very much, the person that may seem uncomfortable, someone that is being isolated. Why? Predators are looking for them too. Traffickers are preying on the psyche of vulnerable people.

Roderick: Do you see men being trafficked for sex as well?

Audrey: Yes, men can be coerced and sexually trafficked as well. There is lots of prostitution of homosexual men in India for example, and elsewhere. LGBTQ young men can be at risk; sex trafficking isn’t limited to a specific gender.

Roderick: Where do you think we are in 2020 with our knowledge of human trafficking?

Audrey: Oh, we’re just scratching the surface. It’s a much bigger issue than people realize. When we think of enslavement, we often think of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The truth is, slavery is still here and it’s happening right under our noses.

Roderick: Your organization LUV, Lift Up the Vulnerable, is here in NYC. Can you tell me more about it?

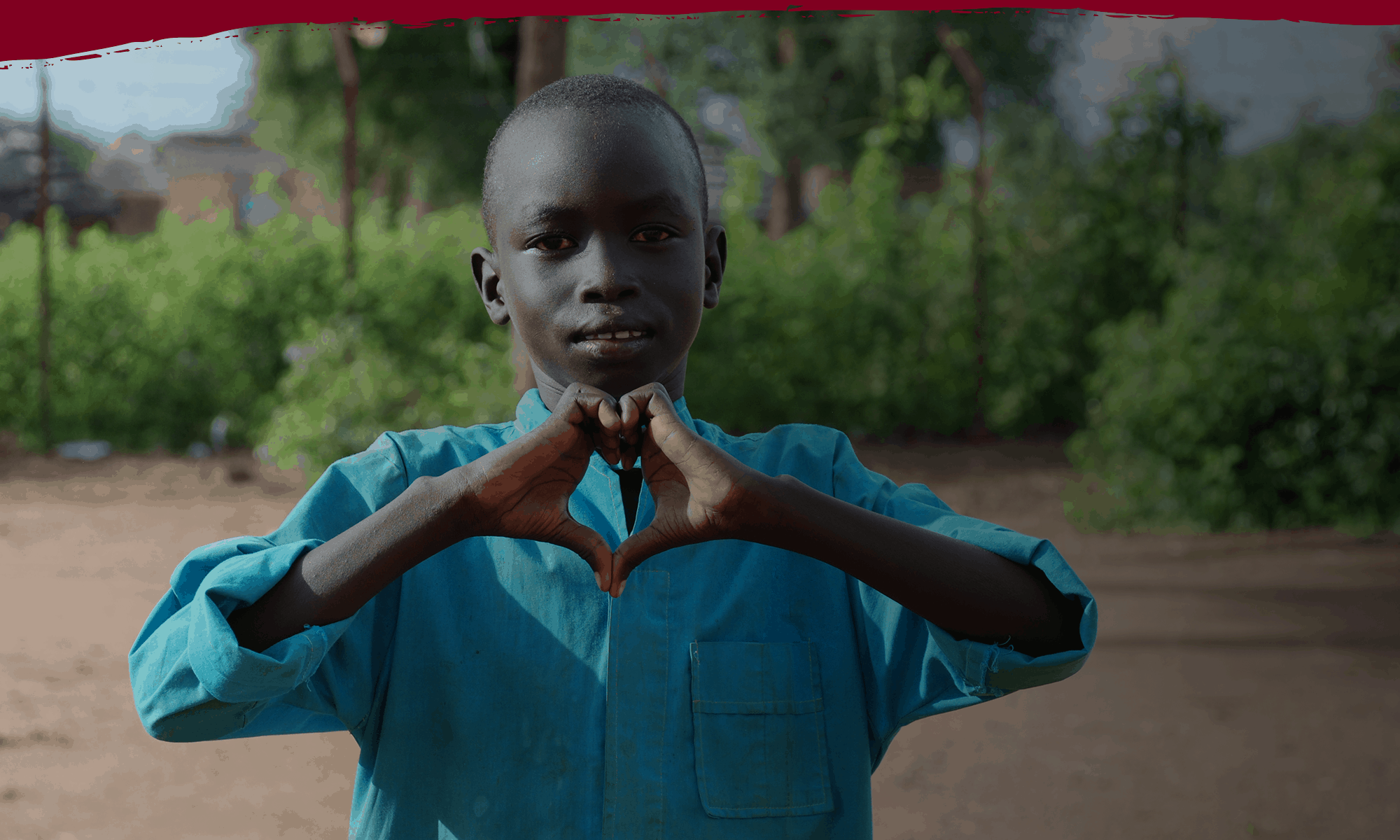

Audrey: Of course. LUV launched in 2019, and we work in the most vulnerable communities. We provide education and medical assistance for children, men, and women, nearly 1,000 of which are in South Sudan. Today, LUV provides over 1,600 children with housing and schooling.

Roderick: LUV works internationally – how different does human trafficking look from place to place?

Audrey: Human trafficking is a multi-pronged issue. It looks different in New York, compared to Alabama, to Sudan or Portugal. To solve issues, we partner with local leaders to help us understand the area and its idiosyncrasies.

Roderick: What do you want people to remember about human trafficking? What do you aim to accomplish with LUV?

Audrey: I want people to remember that we are not just isolated beings – we are connected. An out of sight out of mind mentality doesn’t bring changes to our world. Right now, every headline is talking about how divided we are. This issue is not an issue to be divided on. Human trafficking is about right and wrong.

With LUV, we want to push more communities towards empowerment.

Roderick: Where can we contact LUV, and how do we support?

Audrey: You can support by choosing to participate in our programs offering medical aid, education and housing for vulnerable people. Volunteering is also a welcomed form of support for LUV.

To learn more about LUV and its various programs, visit liftupthevulnerable.org. Roderick Thomas is an NYC-based writer and filmmaker (Instagram: @Hippiebyaccident; email: rtroderick.thomas@gmail.com).