In June 1968 I was working my way through college as a back-office clerk in a brokerage house at 2 Wall Street. It was a deathly dull job. I sat across from Bob Kennedy who supervised reconciling the firm’s trading records for the First National Bank of Boston. In truth, there was only one way a newcomer would be able to distinguish Bob’s desk from mine or the four others he managed: we didn’t have a phone. Not that we minded. Back then when you left home, it was assumed you’d be out of reach for the next nine-plus hours, assuming the subway wasn’t terribly delayed, like that rush hour in November three years earlier.

The 1965 total blackout caused no looting or arson. New Yorkers who took to the streets that night carried flashlights to direct traffic, not Molotov Cocktails. But there was mounting tension in Harlem and Bedford Stuyvesant that spilled over into violence in the Summers of 1964 and 1967. In February 1968, the Kerner Commission, in examining the nationwide spread of rioting in Black communities throughout the “long hot summer” of 1967, concluded that poverty and institutional racism were driving inner-city violence: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal,” they announced. They didn’t know it then, but the “Great Migration” of six million African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North and West was nearing its end, just as the market for unskilled labor hit rock bottom. The result? Fully one-third of Blacks were living in poverty by 1968. Then on April 4th, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, and riots exploded in a hundred cities. But thanks in part to the uncanny insight and personal courage of Mayor John Lindsay (who, by the way, died penniless) the disturbances in New York were minor.

But race remained front of mind that June, as I shifted from part-time to full-time now that my semester was over. Most of my co-workers hewed to popular beliefs that Blacks just needed to get off welfare and work harder. The fact that not a single Black could be found among our clerical colleagues or in the white-only neighborhoods we inhabited led people to openly espouse their views in rather virulent terms, with the words “jungle” and “monkey” frequently invoked.

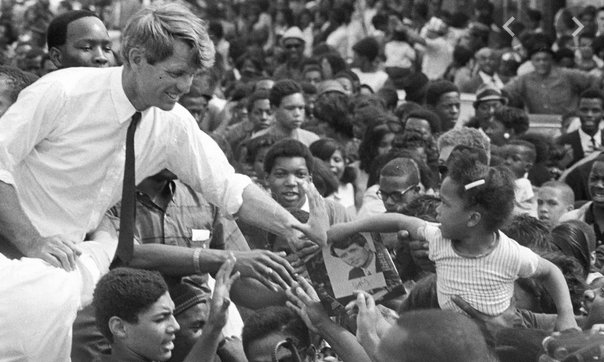

My boss Bob Kennedy would have none of that. He was a hard-driving recently discharged Army grunt who was taking business courses at night thanks to the GI Bill. Unlike most of the middle class strivers all around him, he seemed to have a better-rounded view of the world beyond our desks. He was even-tempered but loved to joke with the junior executive trainees in starched white shirts who dropped by. There would inevitably be banter about his namesake, our New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the brother of another assassinated leader, who was then locked in a dogfight with Eugene McCarthy and Hubert Humphrey for the Democratic Presidential nomination.

Based on what we presumed to be his military service, which he steadfastly refused to talk about, Bob believed we needed to hold the line against Communist expansion in Southeast Asia and therefore favored Richard Nixon’s “peace with honor” approach (although it eventually came out that Nixon was secretly urging the North Vietnamese not to sign a peace deal until he was elected). At the time I styled myself a future CIA spy, studying Russian language and history, and therefore agreed with Bob’s domino theory. But illogically I supported Bobby Kennedy. RFK seemed to ooze empathy and I thought the country needed some of that. Hell, I needed some of that. My large first-generation Irish Catholic immigrant family was so dysfunctional, they hated the Kennedy family. Why? The Kennedys didn’t attend Mass often enough. Oy vey.

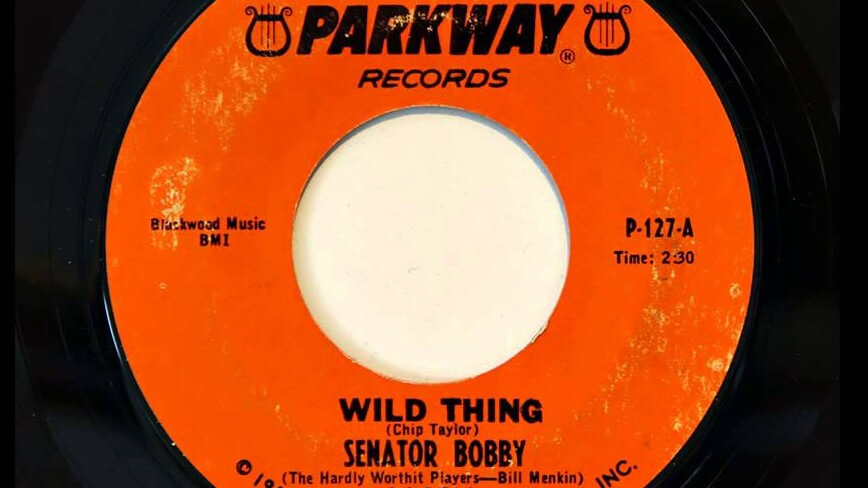

Anyway, Bob had a knack for imitating accents, and he nailed RFK’s unique Massachusetts patois. Hard to believe now, but some comedian sang The Troggs’ “Wild Thing” as “Senator Bobby” in 1967 and had a hit record with it. That was part of Bob’s set list, along with a funny rendition of “Bobby” talking his way through the Doors’ “Light My Fire.”

Then on the evening of Tuesday, June 4th, most New Yorkers went to bed hearing that RFK was the likely winner in the California primary. But as we slept, Kennedy, after declaring victory, was gunned down while shaking hands with dishwashers in a hotel kitchen in Los Angeles. The morning news radio reported he was in surgery. On the way home the afternoon papers reported he was still fighting for his life, but that night, as New Yorkers slept again, he died. Thursday was a difficult day for all of us at work. No matter where you fell on the political spectrum, it just seemed like things were falling apart. Somebody said his body would lie in state at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the funeral would be Saturday. I asked Bob if it would be OK to come back a little late from lunch Friday because I wanted to pay my respects.

Before he could answer me, one of the starched shirts called out, approaching Bob’s desk with a smile, “Hey, that nigger-lover with your name finally got what was coming to him!”

I stood up, infuriated, wanting to say something, do something, but I said nothing, standing there motionless as Bob Kennedy decked him with a solid right cross. Down the junior exec went, broken jaw and all.

Back then, when somebody got fired, there was none of the “Security will escort you to clean out your desk” ceremony. You were just gone. The next day I thought I saw Bob up ahead on the long thick line that stretched from the Cathedral down East 51st Street for what seemed like forever. I’d been waiting for an hour by then and didn’t want to lose my spot, but I needed to say goodbye to Bob more than Bobby.

It wasn’t him.

In the Fall of 1967 Bob Dylan recorded songs in Tennessee which seemed to presage the year we were about to experience. In “All Along the Watchtower” he told us “the hour is getting late.” But it wasn’t until late June of 1968 that I fully appreciated Dylan’s prophecy. Murray The K, a popular AM disc jockey, had switched to FM and miracle of miracles, my Flatbush Avenue pizzeria had tuned him in one night while I sat eating a Sicilian slice on my way home. And for some reason, Murray The K played Dylan’s slow Biblical lament: “I dreamed I saw St. Augustine, alive with fiery breath. And I dreamed I was amongst the ones who put him out to death. Oh, I awoke in anger, so alone and terrified. I put my fingers against the glass and bowed my head and cried.”

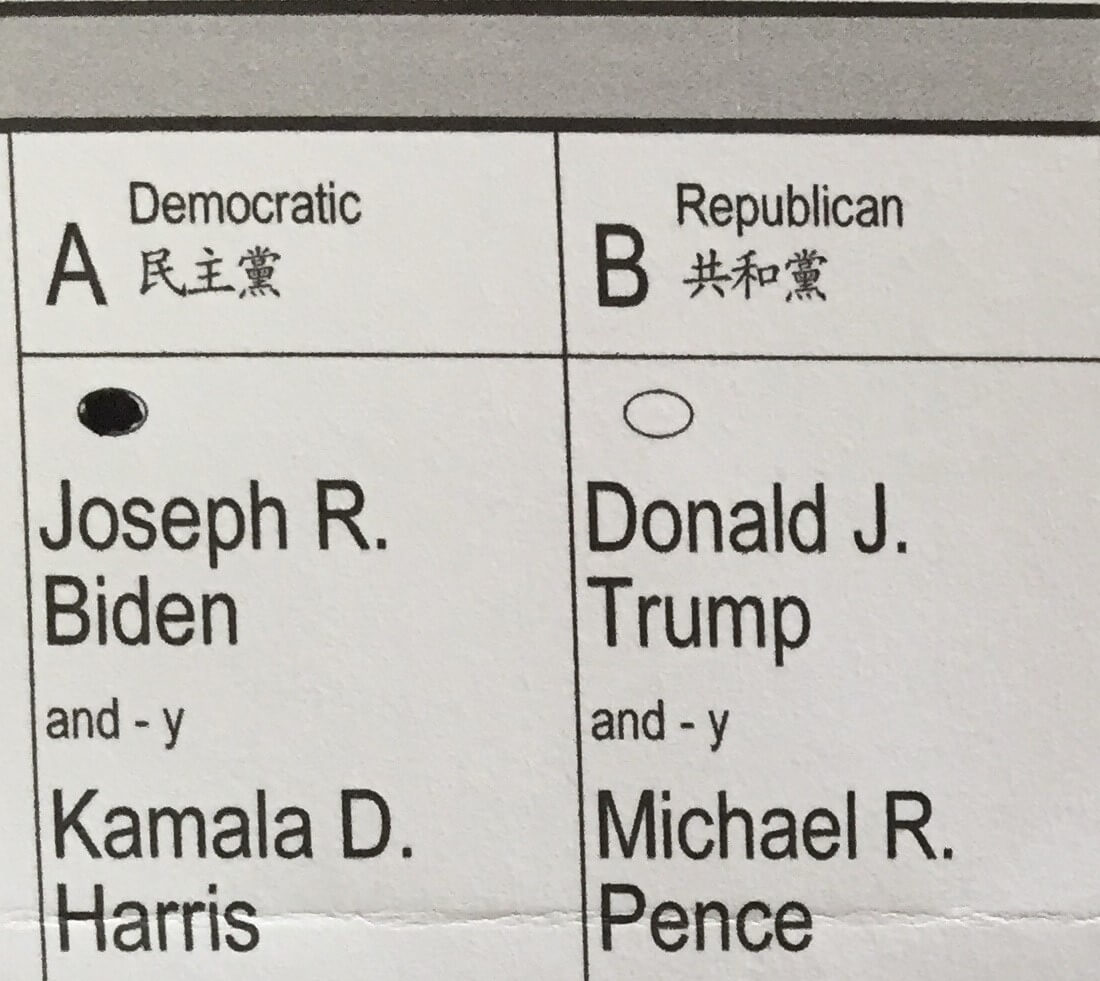

I still think of Bob Kennedy when I hear that song. And I plan to cast my vote for empathy, not hate, this Fall. The hour truly is getting late.

4 Comments

How far we’ve come, Joe. How far we’ve fallen. How little is left of our sense of common decency in defense of the common good.

Peter, You managed to sum up my pitiful thousand words in a perfectly chosen two dozen. Thank you. I also thoroughly enjoyed your web site. Murray The K got me through many a lonely teenage night! And by the way, I’m hoping he was a guest DJ on WOR-FM that night “St. Augustine” played in my pizzeria. If not, readers should feel free to sue me, but they’ll have to wait in line. “Memories are bullets. Some whiz by and only spook you. Others tear you open and leave you in pieces.” ― Richard Kadrey, Kill the Dead

Joe, that’s a wonderful piece.

Thank you

Thanks, Bob.