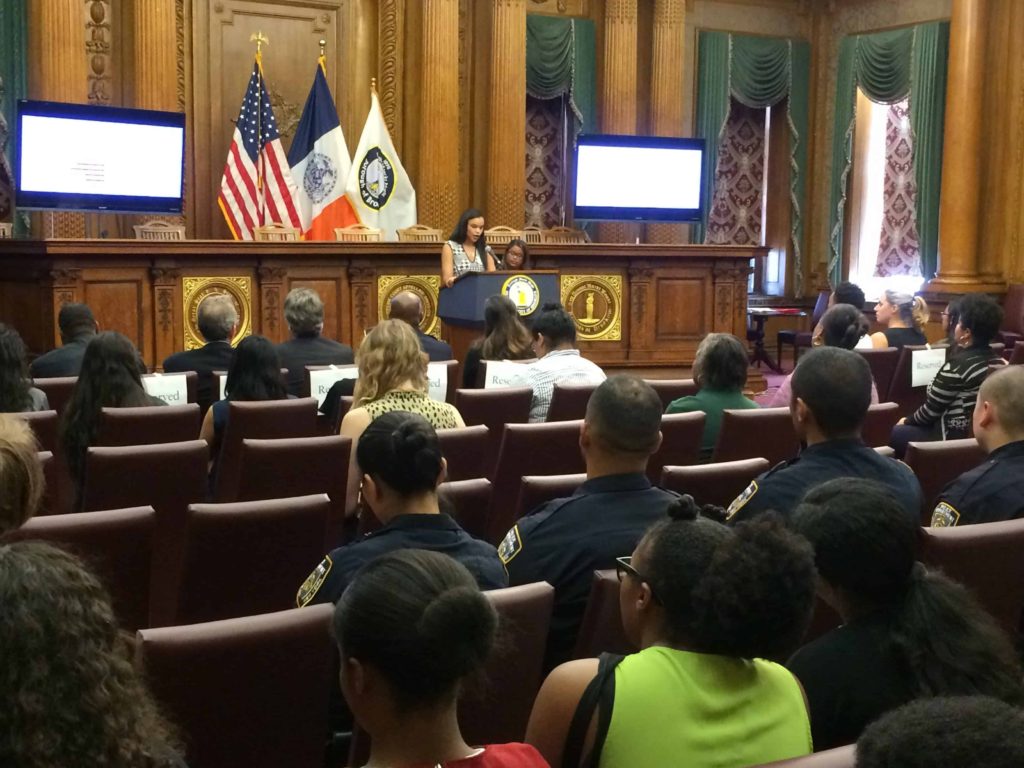

Bridging the Gap co-leaders, Sabrina Carter and Gleacy Mejia, take the podium at Brooklyn Borough Hall. Photo by George Fiala.

Bridging the Gap co-leaders, Sabrina Carter and Gleacy Mejia, take the podium at Brooklyn Borough Hall. Photo by George Fiala.

The woman wears a laurel crown and a long white robe. Though serene, she cradles an ax. Beneath her feet, a motto in outdated Dutch reads:

Unity makes strength.

This old flag commemorates Brooklyn’s stint as an independent city in the 1800s. It greets visitors inside an entrance at Brooklyn Borough Hall, framed on a wall just beyond a security desk. On Tuesday, nearly 130 guests passed this flag on their way to a Red Hook Community Justice Center event that confirmed the borough’s mighty motto.

The Justice Center’s Bridging the Gap program, which held its one-year anniversary on July 18 at Brooklyn’s Borough Hall, brings police and youth together in the spirit of mutual understanding. Five sessions after the initiative launched in 2016, Bridging the Gap remains committed to providing safe spaces for young people to get to know—and question—their local law enforcement.

In the city that invented stop-and-frisk, any attempt to unify police with the policed seems ambitious, but the last few years have shown signs of progress. The controversial policing practice was ruled unconstitutional in 2013, and Police Commissioner James O’Neill’s neighborhood policing initiative has expanded across the boroughs for the last two years.

The Justice Center is known for innovative approaches to police-community relations, like training police officers as “Peacemakers” in a program adapted from Native American Indian conflict resolution techniques. What’s Bridging the Gap’s unique contribution to the movement? Perhaps its face-to-face meet-ups in a friendly environment.

“There’s nothing better than cops and youths sitting down talking…This is something that has never been done before,” a keynote speaker, Assistant Chief Rodney Harrison, told the crowd on Tuesday. Harrison, who oversees the NYPD’s neighborhood policing program, has been a member of the force for 25 years.

Is Bridging the Gap sustainable past year one? Its promise might be measured in early signs of retention.

The program’s first event in summer 2016 involved only five officers and 30 civilians at the Justice Center. Since that modest beginning, a couple hundred youth have participated in the program’s pilot year, according to Justice Center Deputy Director Viviana Gordon. And most participants return after their first session, for events ranging from discussions to field days.

“At the core of our mission at the Justice Center is our desire to build public trust in the justice system and make our neighborhoods safer,” Project Director Amanda Berman told the Star-Revue.

“Bridging the Gap embodies that mission by bringing together youth, community, and police, and creating a safe space that encourages meaningful dialogue and positive interactions. These conversations are not always easy to have, but the success of this series is a testament to the commitment from all sides to work together to make our communities safer and stronger.”

A sea of navy blue uniforms waded into Brooklyn Borough Hall’s impressive courtroom on Tuesday, seating themselves in the back. Youth, parents, and other community members settled up front, taking in the impressive venue’s gold-trimmed molding and wooden columns.

Deputy Brooklyn Borough President Diana Reyna offered a warm welcome, inviting guests to call Borough Hall “your house.”

“I know firsthand…what builds a community is when everybody is involved,” said Reyna, adding that her husband is a NYPD lieutenant. She’s also empathetic to youth perspective of law enforcement as the mom of two young boys.

Reyna emphasized that a well-meaning project like Bridging the Gap is a process that takes time. To build trust, a community first needs to build relationships.

“As Borough President Eric Adams always says:‘See the man behind the uniform.’”

Reyna reminded the room that the NYPD is recovering from the unprovoked shooting of Officer Miosotis Familia that occurred earlier this month in the Bronx.

Some Bridging the Gap participants have had perfect attendance at all five sessions. One of them is soon-to-be high school senior Marcus, who was honored on Tuesday as a speaker.

“At first I thought it wasn’t gonna work,” Marcus addressed the crowd from a podium. “What I’ve realized is that not all police are bad. Yes, they make mistakes. But they’re human, too.”

Recent high school grad Karime also turned up to every Bridging the Gap event this year. The program taught her not to judge all police by the behavior of a single cop, she said.

Karime shared that she hopes to attend John Jay College this fall for forensics, but wherever she studies, she will be the first generation of her family to attend college.

A beaming PSA1 Officer Terence Williams took the stage next. “I’m a little nervous, so I’m gonna need some smiles I see right now,” he said. The audience was already smiling back.

This moment of confessed vulnerability—especially from someone sporting a gunbelt—made a humanizing portrait of a man beyond his uniform. Later in the evening, two other police officers announced their nervousness when they took turns to speak.

Officer Williams was one of the first five police officers to join Bridging the Gap. He remembered the first event at the Justice Center: “It felt like a room full of 300 people—it felt that intense…[The young people] liked the fact that they were heard…We answered some very tough questions.”

For Williams’ five and a half years on the force, he calls his role as a neighborhood coordination officer (NCO) his “most prideful position.”

Started by Police Commissioner O’Neill in 2015, the neighborhood policing initiative seeks to make NCOs accessible liaisons between the department and the community. Chief Harrison has been the operational commander of the program, which is currently implemented in 47 precincts and nine housing commands.

Photo by George Fiala.

The day before the Borough Hall event marked the third anniversary of the Eric Garner tragedy. The Staten Island man’s death by chokehold at the hands of Officer Daniel Pantaleo became another disturbing statistic of police brutality.

Harrison was appointed to Staten Island on the heels of the incident, where he worked closely with Garner’s family and community. Harrison reflected on that assignment as “probably one of the most humbling moments of my career…Going back to that phrase—’build that bridge.’”

Harrison urged the audience to get to know their local police personally, like a dentist or doctor, and challenged everyone to meet the cops assigned to their precinct before they left the event.

New York state Assemblymember Felix Ortiz joined the list of speakers, recalling his brother who rose the ranks of law enforcement and became an FBI agent despite a language barrier.

The event took an interactive turn with an icebreaker that prompted getting to know new faces. Sitting one seat over, the first person this reporter met was high schooler Marcus’ grandmother, Mary Whitehurst from Crown Heights.

“I’m very proud of him,” she said with a smile. “Sometimes we argue, but today I’m very proud of him. He’s a very good kid.”

One badge-toting attendee, Harlem-based NCO Tammie Garcia, has already talked to Chief Harrison about bringing a program like Bridging the Gap to the 28th precinct. “We don’t have this. It would be nice if we could bring what we’re doing here, uptown.”

After refreshments were served, youth and police returned to the courtroom for break-out discussions. Each group of two to three police officers and half a dozen youth received a sheet of questions to prompt dialogue. The officers seemed to relish the opportunity to dish some on-the-job insight while the young participants listened with rapt attention.

Housing Bureau Officer Ronald Woody shared some intimate personal history with his circle—he was born at Rikers Island while his mother was incarcerated.

Woody admitted that his distrust of police was an attitude learned from growing up in the city’s public housing developments.

“Me hating the police was taught to me by my siblings, family members, and friends…I was taught not to trust a police officer just like many of our youths now,” he told the Star-Revue.

After playing professional basketball abroad in lieu of college, Woody joined the force first as a school safety agent. Both he and his wife have served as correction officers at Rikers.

“People say when you have a gun and a badge, that’s power,” Woody told his group adamantly. “But it’s not. It’s a responsibility.”

Another NYPD member included PSA1 Officer Christopher Cambrelen. This was Cambrelen’s fourth Bridging the Gap event, and he attended the anniversary at Borough Hall on his day off.

“I believe it builds a bigger circle,” said Cambrelen, who likes befriending community members so he can say hi to them in passing.

The Justice Center’s Sabrina Carter and Gleacy Mejia—both graduates of Red Hook Youth Court—are the dynamic duo behind Bridging the Gap. Looking around the room full of (mostly) men, Carter said it felt all the more powerful to be in such a productive partnership with Mejia.

“We started this not knowing what could happen,” said a smiling Carter, who’s spent 15 years at the nonprofit.

“We were very apprehensive,” added Gleacy, citing divisive media coverage of police as a sensitive factor to neighborhood perception of law enforcement.

Gleacy tried out a prototype of the program at John Jay College, but Bridging the Gap officially kicked off at the Justice Center, where she’s worked for five and a half years.

Now the fully functioning program recruits youth, ranging from 10 year olds to 21 year olds, from Good Shepherd Services, Miccio Community Center, the court’s sister projects, family of staff, and word of mouth.

Interactive session

To wrap up the two and half hour event, guests were invited to the podium to feedback on their experience in the discussion groups.

16-year-old Zachary said he “learned how [police] feel about all the things they wear,” including the body cameras that are worn by some members of the force.

For PSA1 Officer Krunal Patel, whose Tuesday attendance marked his third Bridging the Gap event, “It’s been awesome getting to know these guys and girls over the year…Getting to be known by name—it’s a great feeling.”

“I’m looking forward to whatever next year brings.”

Carter and Mejia are eager, too. They have already been in contact with Sunset Park and Staten Island precincts about growing their program. “We hope to be the people who go into communities to set this up,” Mejia said.

But for implementation, the Justice Center reps know that no one size fits all.

“Every community is different,” stressed Mejia. She pointed to Sunset Park as an example, whose diverse Chinese and Latino community might prioritize certain immigration issues in a Bridging the Gap program.

Four months into the job, PSA1 Officer Jeffrey Minaya was prodded up to the stage by rousing cheers from his peers.

“I explained to [the youth] that I was in their shoes not too long ago,” said Minaya, reflecting on his discussion group. “Every person in here has the same uniform, but we all have a different story.”

Carter momentarily took the mic back to follow up on Minaya’s remark. The inverse is true, too, she told the police present.

“Don’t judge one teenager by judging a group of teenagers.” The crowd affirmed with cheers.

Certificates were given out to the cops and civilians as a token of their participation. The stately courtroom would return to order tomorrow; tonight was for selfies and hugs.

Before the crowd dispersed, Carter took in the neighborhood movement she helped create for one last time. “This is going to be history, so make sure you remember that, ok?”

For more information on the Bridging the Gap or any other Justice Center youth programs, visit www.courtinnovation.org/project/red-hook-community-justice-center.