The jazz world is vastly different than it was 100 years ago.That probably seems obvious, in that the world may seem different than it was 100 years ago, though that is mostly superficial and centered around technology. What I mean is the there are key aspects of the society that gave birth to jazz that have changed and in many ways no longer exist, and that has to do with vice and organized crime.

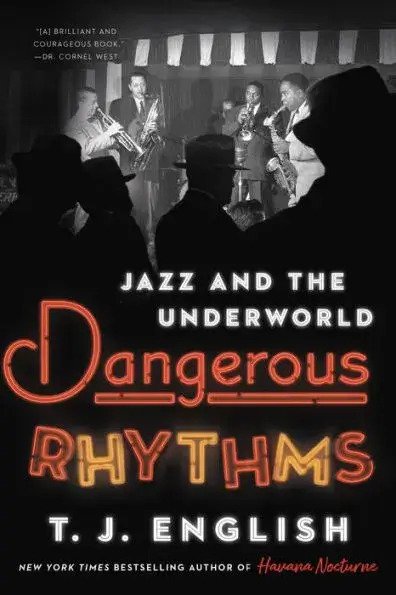

That’s the story that T.J. English tells in his new book, Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz And The Underworld. It’s one that jazz heads will know, at least in how it is reflected in Louis Armstrong’s life story, but English does rope in vital parts

of the history of the music that are either specific to how jazz developed (especially in Kansas City) musically or how it worked as a business, that example being Frank Sinatra. (Jazz heads may gnash their teeth about Sinatra being in the book, but he, and Bing Crosby before him, was important for how he learned from jazz musicians and brought their ideas to a mass audience—even if he strictly never sang jazz—and in turn jazz players learned from Sinatra’s marvelous phrasing. Jazz and pop first met and mingled over what’s become known as the Great American Songbook, and Sinatra swung the hell out of that on his great albums with Duke Ellington and Count Basie.)

For anyone unfamiliar with and interested in how jazz came to be, the book might well be mind-boggling. This is not musicology, but social history, which is the part that musicologists almost always leave out and is always where the music begins, before anyone plays a note. This is about how musicians got the chance to make the music that became jazz, and develop it and bring it to the world. And yes, it starts in New Orleans where all the myths say it started, in the brothels, gambling parlors, and other vice dens of Storyville, the de facto red light district where the citizens of the demimonde were allowed to congregate and do their thing.

People like to be entertained, and a brothel was not just a place to pay a woman to have sex, but to have a drink, hang out, socialize away from both work and home. People who ran brothels liked to make money, the more satisfied customers the better, and so they hired musicians who were playing that crazy new style called “jass.” That included Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, without whom we would neither have jazz as we know it, or pop music (which was pretty much created singlehandedly by Armstrong when he started singing on record). The customers were happy, the madams and pimps were happy, and the musicians were not only happy but got to try new things and create the consensus of rhythm, style, and ensemble interplay that became jazz.

The music has been respectable since the swing era, but in the ‘teens and 1920s, jazz was as suspicious and threatening as drill is supposed to be now (moral panics never go away, it’s just the names that change). It was hot, it made people want to do drugs and have sex—and of course it did, because it was being played for people who were there to do drugs and have sex! While jazz is now a niche-cult music, since the time of its greatest popularity in the middle of the 20th century it was, socially, a signifier of bourgeois taste and status, meaning that at least in the public regard the origins in what many people (especially white audiences) might consider unsavory lifestyles had been filtered out.

How quickly did that happen? In 1928, Armstrong released “Tight Like This,” where he and pianist Earl “Father” Hines discussed the following proposition:

Oh it’s tight like this

No it ain’t tight like that either

I said it is tight like this

… tight like that there

Oh it’s tight like that Louis

No it ain’t tight like that either

Now it closes like that

Within the space of one generation, in 1951 Dave Brubeck began touring college campuses, bringing modern jazz to educated young white audiences across the country. His quartet was tight, but not like that. Although with the amazing Paul Desmond playing alto sax, it was plenty bluesy. The blues element in jazz is enduring and essential, not just musically but because that’s the connection to making music from and about the human experience. A Desmond solo may not be quoting “Jake Walk Blues” or “I Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl,” but it has roots in the same place.

Again, the outlines of this are familiar, and if not, all it takes is listening to what Armstrong and Morton are telling you without taking it as any kind of metaphor. The lesser-known but deeply fascinating and important part of this story comes from Kansas City, where the local Pendergast political machine, based on the T.J. Pendergast Wholesale Liquor Company, kept Kansas City wet, happy, and flush during Prohibition.

Speakeasies, like brothels, wanted musicians, so did wet nightclubs, so did joints with live sex shows, and along came the combos and the dance bands which morphed into the famous swing bands, known for the sound of the territory they came from. Kansas City was the launching pad for Basie and Jay McShann, a hell of a bandleader in his own right and whose place in history was cemented when he hired the young Charlie Parker.

The rest is history. Prohibition created a void that was filled by organized crime. The Mafia, already part of society in New Orleans, Chicago, and New York accumulated tremendous wealth and power giving people the thing they wanted that the government said they can’t have (another familiar story). The interesting part of this that the gangsters themselves wanted the social status and cache of being close to the musicians. What Francis Coppola’s The Cotton Club tries to show but doesn’t quite achieve is how having Duke Ellington in your club, and all the swells who came to see his band, reflected glory on the gangsters running the place—they weren’t just wealthy merchants, they were admired figures in society. That’s exceptionally valuable to many, many people, and why the Kochs fund the ballet.

Sinatra is paramount in this regard, and his music career was both enabled by the Mafia and allowed the Mafia to reach into the record business and Hollywood. That in itself is an enormous story, but English gives a good outline of it, as well as weaving all the decades and locations together into a fabric that was truly connected. Economic and social culture have always moved from New Orleans, up the Mississippi River, to the Midwest and Chicago, and from there to New York City and parts West. In the 19th century, that meant cotton and the slave trade, 100 years ago it was opium and booze, jazz and blues.

Until the 1960s that is. That’s another story in itself, one where radio, baby boomers, and the splitting of white and Black audiences pushed jazz to the side, leaving the field open for rock and soul and things beyond. Jazz doesn’t just go to college, it has been taught in college for generations. This is nothing against the music, which is still as great as always, but it is important to know how things began for two reasons. One is that an imagined, Arcadian past when jazz was somehow pure is a pernicious myth that has always worked against the music, and the other is that jazz has been compartmentalized as a high-class, even intellectual form, one supported by Lincoln Center no less. But it’s just music, as Charlie Parker himself said, and “real gone music” as Sid Torin once replied, and music since before civilization has often been about getting up and getting down, especially when the man suppresses that. It’s good for jazz to remember.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

One Comment

Pingback: Jazz - Meraklı Havuzu