What a year. Like a lot of eras, 2020 doesn’t fit easily into pre-defined calendar definitions. Did the 19th century end in in 1900 or 1914? Did the World Wars end in 1945 or 1989? The 20th century certainly came to a close on September 11, 2001, or was that just America? And 2020 probably began with the first Democratic Primary events in 2019, and it’s not going to end until we started getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

In music, the main story for 2020 has been what’s not going on—live, in-person shows. A story then about a nothing, a non-story. There’s another side to that, though, which is how the year has meant renegotiating our relationship with recordings. If enjoying music in the previous years meant a mix of albums on the stereo and live experiences, this year has been trapped in aspic, if not amber. Music has been, for me, CDs, cassettes, streaming, radio, and the occasional happenstance street-corner performance.

Listening has been different, and so my listening has been different. Since March, I’ve been deeply drawn to ambient music and field recordings, music that eschews formalism and teleology for a sense of place, sound that carves out a location and a still point in time, sound that I can step into, away from the grey, grinding stasis of 2020.

And here we are, at the end of this calendar year, hoping (as I write this Thanksgiving week) that maybe Spring 2021 might mean we can put the face mask away and step into a bar for a drink or a club for some jazz? End of the year is list time—Santa’s on his way, after all. The calendar does make a convenient point in time for lists, and, reader, I think lists are useful. Decisions must be made, and now’s the time. I’ve already submitted my experimental picks to The Wire, and I have to make a list of jazz albums for the NPR Jazz Critics Poll. In other words, these things are both rigorous and merely a snapshot of a moment in time. In two weeks, I will have heard other albums that will have an affect on everything on this list. But December calls, column inches are available, and at this moment in time, my baker’s dozen of the best new jazz albums for 2020 is:

- Tyshawn Sorey, Unfiltered (Self-released and available at Bandcamp)

This is an unranked list, except for this album, which is one of the great jazz recordings of the 21st century. Unfiltered is a long-form composition that encompasses tremendous playing from Sorey’s sextet and has a shape that builds to an awesome pinnacle of emotional and intellectual magnificence. This is a classic that every jazz fan should know.

All that follow are a worthy second-place tie. I pointed out my involvement in ambient/field music above to frame this list—everything on here had the power to break through the comfort of the sonic gauze I frequently sought.

- Gregg August, Dialogues on Race (Iacuessa)

- Wolfgang Muthspiel, Angular Blues (ECM)

- Whit Dickey/Matthew Shipp/Nate Wooley, Morph (Tau Forms)

- Immanuel Wilkins, Omega (Blue Note)

- Kaleidescope Quintet, Dancing on the Edge (Dot Time)

- Jean-Louis Matinier/Kevin Saddiki, Rivages (ECM)

- Marcin Wasilewski Trio, featuring Joe Lovano, Arctic Riff (ECM)

- Lakecia Benjamin, Pursuance: The Coltranes (Ropeadope)

- Luke Stewart, Luke Stewart Exposure Quintet (Astral Spirits)

- JD Allen, Toys/Die Dreaming (Savant)

- Roots Magic, Take Root Among the Stars (Clean Feed)

- Bobby Previtte/Jamie Saft/Nels Cline, Music From the Early 21st Century (RareNoise)

- Chien Chien Lu, The Path (Self-released)

Yes, that’s thirteen, so let’s call it a baker’s dozen following Unfiltered.

That list is albums recently made and released in 2020. The year has been a great one for archival music, unearthed tapes that have essentially never been heard before, or older albums reissued with illuminating new material. Resonance Records, which specializes in obtaining private performance tapes and issuing them with informative notation, takes pride of place this year, with three ear-opening sets:

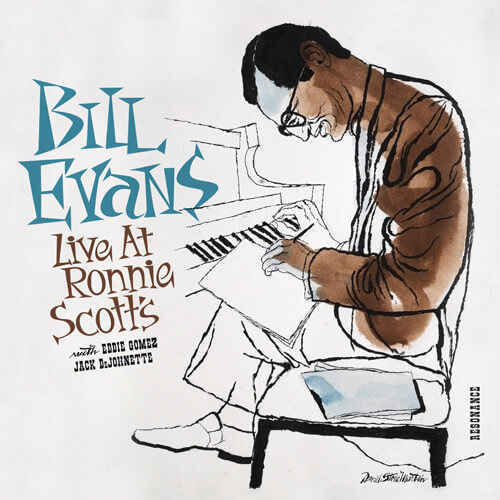

- Bill Evans, Live at Ronnie Scott’s

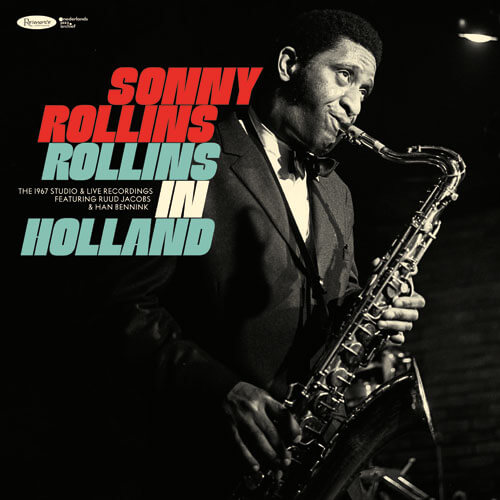

- Sonny Rollins, Rollins in Holland

- Bob James, Once Upon a Time: The Lost 1965 Studio Sessions

The music on each of these is uniformly excellent, and the context is equally important. Evans’ trio was a short-lived group with Eddie Gomez on bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums (DeJohnette made the recording from the bandstand), and this was a sweet spot in the pianists’ career, a moment when he was in full maturity but before his drug and alcohol problems diminished the sonic and emotional beauty of his playing. The Rollins set collects studio and live performances with bassist Ruud Jacobs and drummer Han Bennink. Bennink has had a long, wonderful career as an eccentric wild man, but his playing here, in 1967, is both relatively conventional and sharp as a tack. Jacobs, unknown to me until this release, is fabulous throughout, and the naturalness and invention of the playing rivals Rollins’ Village Vanguard recordings, which are classics of jazz discography. James is best known as a practitioner of smooth jazz; this 1965 session is something completely different. He starts with a modern, swinging style, and explores plenty of avant-garde territory, more experimental art music than jazz. And it’s damn good.

The mail-order speciality label, Mosaic Records, released a 7-CD set of Paul Desmond, The Complete 1975 Toronto Recordings. The ‘70s were an era when Desmond was only an infrequent performer, but up in Toronto he was playing with friends like bassist Don Thompson, who made these tapes. In the club setting, he’s as suave, hip and bluesy as ever, with more than a little fire. Desmond was one of the greats, and this is a great example of his art.

In the same line is the Sunnyside release of Charles Mingus: At Bremen 1964 & 1975, two concerts from those years and that city. Mingus’ 1964 sextet, with saxophonists Eric Dolphy and Clifford Jordan, trumpeter Johnny Coles, pianist Jaki Byard, and drummer Danny Richmond, was one of the finest ensembles in the history of jazz, and at their peak they were THE finest, bringing the past into the present, inventing new ideas, and turning on a pinhead in an instant, no matter the pace. That band is well-documented on live recordings, most of which are astounding, and while this one is fine it’s not the apex of their 1964 tour. That’s a minor complaint, the difference is between the heavenly and the merely stratospheric.

The 1975 date is mind-blowing, however. As with Desmond, this is a fallow period in Mingus’ career (he was dead four years later from ALS). But the band, once again, is hellacious; right-hand man Richmond was still there, with trumpeter Jack Walrath, saxophonist George Adams, and pianist Don Pullen. If the 1964 set is a little ramshackle and unfocussed, the later date is burning, with swaggering good humor. Warts and all, this is a major addition to Mingus’ discography.

These are all great recordings, give to yourself and others generously, and best for the holidays.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/