What does it mean to make an album in 2023? They’re still being made, Billboard magazine still tracks their sales, but just what is that thing itself, the album, and why are they made as albums?

The subject on this page each month is jazz, but these thoughts apply to all kinds of music, and are especially relevant to popular music. Still, it comes from all the jazz (and classical, metal, avant-garde, experimental, etc albums that come my way as a music critic) releases I hear, the majority of which just don’t make any sense as albums. When an artist feels they have enough good material, they put it together into a release. But what I’m thinking about is: why an album? Why these albums that come out? And again, what is an album anyway?

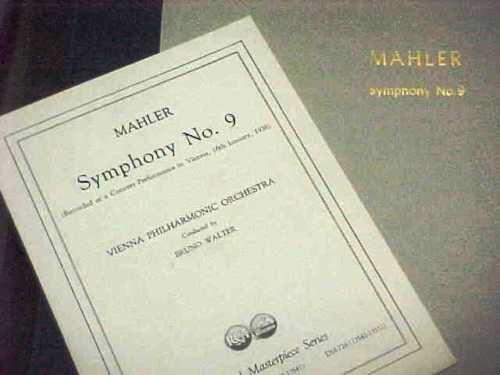

The very idea goes back to the record album (not the LP) which was literally an album that gathered together a set of 78 rpm discs. Since they couldn’t physically hold much more then three minutes of analog grooves on a side, anything from a set of more than one pair of singles to the famous 10-disc recording of Bruno Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra playing Gustav Mather’s Symphony No. 9, in concert on the eve of the anschluss in 1938, came in a jacket that collected all the media, akin to a photo album.

Albums then, at first, were just something that held some music together, and they didn’t necessarily have to have the form of a symphony recording. Albums as we know them today are an implicitly coherent and self-contained package of music, and that came with the commercial development of the long playing record in the late 1940s (the technology had been around since the early 1930s, but the Depression curtailed commercial implementation). The first 12” microgroove vinyl LP, playing at 33-1/3 rpms, was the great violinist Nathan Milstein playing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with the New York Philharmonic, conducted also by Bruno Walter (shout-out Walter’s legacy, he was one of the great classical musicians of the 20th century and his artistry was essential to the rise of Columbia Records). Albums now could tell a story.

Pretty quickly, artists realized that they could integrate the music and the format (not just the two LP sides but cover art, liner/sleeve notes, etc) together so that not only did the pieces fit onto the disc, but the way the music worked together defined the album, and made it something deliberately different than the live music experience. That man meant concept albums like Frank Sinatra’s In The Wee Small Hours, and Max Roach’s We Insist! It meant Charles Mingus playing live in the studio as if it was a nightclub, complete with between-tunes patter (Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus on Candid). Miles Davis did something similar with his run of albums for Prestige with his John Coltrane Quintet; playing through with no edits or alternate takes and keeping the total duration around the same as a live set. Even revolutionary music like Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz was made with the LP in mind, with the duration under control and the music formed to make sense as an A and B side of a disc.

In retrospect, it’s easy to see that one of the key factors in the great LP era for jazz, from the mid-1950 s to the mid-1980s, was that the records were conceived and produced with the medium in mind. Albums like Mingus Ah Um and In A Silent Way are extraordinary recordings and documents of music making because they were edited and sequenced to fit nicely into the durational limits of the LP (themselves defined by how many grooves could fit and be playable on a 12” disc). Later expanded CD reissues of both prove this, as original, unedited takes are longer and lesser, with stretches of so-so music that weaken the overall effect (it’s no coincidence that the great Teo Macero was producer for both, wielding judgement via a razor blade to get the best possible results onto vinyl). That also has a subtle point within, which is that even if the music was recorded from live playing in real time, these were made as recordings, with artists striving for the best possible take to be pressed.

There are still new albums coming out, but in the age of streaming services and digital downloads, there seems to be much less thinking about the purpose of putting music together as an album. Vinyl has made a comeback, and cassettes are still around and are a great medium when you don’t have any budget (they mainly seem limited commercially by how hard it is to find a decent, inexpensive tape deck). But our era is defined by the CD and digital media in general, and so many jazz albums have that in mind, often with an hour more of music.

An album is a limited set of music, with a finite duration that may or may not be physically limited by the medium on which it’s produced. A successful album is coherent within it’s entire duration, without superfluous music that diminishes that coherence wither through redundancy or simple nonsense. More music doesn’t mean better music. Mingus Ah Um is about 45 minutes and every moment is great. An album is only as good as its weakest moments—think about albums you’ve heard that have eight great tacks and two meh ones, and that let-down feeling that comes when it hits one of those—and Macero sliced away all the duller moments so that nothing is weak.

It’s a mystery to me what jazz producers do on many recordings. Albums come out that have 40-45 minutes of good music and 20-30 minutes that are bland, awkward, dull. A recent release on one of the best independent labels, known for the stylish and innovative music they produce, is a two-LP set that would have been a fantastic single LP but that, stretch across a second disc and about 80 minutes total, looses all the sensuous grooves and enticing direction as it dissipates, via small doses, into vapidity. Through the first side, I was looking forward to playing it again, and once the last side hit, it was both bored and exasperated, wondering when it would end. The producer in this case was the artist—always a danger—and apparently no one suggested to them that maybe a single disc would have been better.

Listeners have some responsibility in this too. There’s something there about how we get conditioned to listen. The kind of discourse that goes on around books and movies about literacy in the medium could be applied to music as well, at how to listen. There’s a threshold to the time we can give to an astute listening, and that’s certainly effected by the experience of both a 22 minute LP side and a five hour playlist. The old formula of the Blue Note albums, which was a model for how to make an LP, has now given way to a formula that almost seems to accept a durational dullness. I see this in both the music people praise and the way audiences are at shows, taking in a kind of sluggish sense of grooviness (not groove) and seeming to crave it, like a soporific comfort is all that want.

But this is jazz, baby! Jazz is about life, it should be sharp, vital, for moving not swaying, it has things to tell you. One of the amazing thing about music is how much intellectual, aesthetic, and emotional information can be found in the smallest amount of material, one note, one second. No other art form can come close to this. Don’t waste it.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/