Transitions are beguiling, that period when a thing is changing into something else. It’s part of nature, of course—it’s the story of the universe—and it’s essential in all the arts. The ephemeral, performing ones, especially dance and music, are all about movement and transitions through time.

Not all music is the same, obviously, and the way transitions are handled and their purpose differs by individuals and eras. The clearest way to hear this is through music that defines itself through form above all else, i. e. Western classical music. One of the satisfactions of Haydn is hearing how he lays out eight bars of an idea, repeats it, then fits in a proportional transition to a new idea: sonata form!

Form grew more personal and complex through the 19ᵗʰ century, reaching an end in pieces like Sibelius’ Symphony No. 7, which is in almost constant transition until the last measure, when it finds its essential meaning. But that wasn’t a modern thing, and it’s not right to think of the use of musical transitions as signifying accumulated knowledge; polyphonic vocal music of the Renaissance is also in constant transition. We’re no more complex, nor apparently wiser, then they were in Rome in the 16ᵗʰ century.

We hear the transitions in classical music only after the composers figured them out, in jazz we hear musicians improvising their way to and through them, improvising the trustees themselves. The essence of jazz is that it a process of creativity and exploration—improvisation, like life. And because jazz has coincided with the development of recording technology, almost every movement and revolution in Jazz has been preserved on audio. Maybe the single best example of this is the Miles Davis: Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965 box set, where you can hear Miles and his second great Quintet (Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams), improvise their way out of hard bop and into a new conception of small group jazz, in real time.

The exception is arguably the single most important revolution in jazz, which was the creation of be-bop, the movement that transformed jazz from a modern popular music into a modernist art music. There are incredibly important early bop recordings like “Ko Ko,” recorded by Charlie Parker and his Quintet, November 26, 1945, but the music is established be-bop, the transition has already happened. How it came to be, the sound of that, is still mostly a mystery. Thats because from 1942-44, when Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were experimenting and creating the new style, the Musician’s Union was on a nationwide recording strike, and no one made any records. There were radio broadcasts and some transcriptions of the same, and a small number of to me recording the musicians themselves mede of jam sessions—there are famous ones made by Bob Redcross of Parker and other musicians jamming in his apartment—but the latter only amounts to a few flaking fragments left from a fresco lost to time.

There were transitional musicians too, not necessarily working the way from one idea to another but rather standing in between the two different ideas, either in an independent way, like the great pianist Art Tatum, or friendly with both but not fully inside either. That’s the case with Don Byas.

Byas was one of the great swing era tenor players. He had a warm, buttery tone, fleet fingers—his swift improvising on “I Got Rhythm” in duet with bassist Slam Stewart at Town Hall in June, 1945 is a landmark jazz recording and for a time kept listeners aware of Byas’ existence because of its inclusion on the 6-LP Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, a once coveted set released in 1973—and a way with a ballad that emphasized beauty and purity of feeling. The Don Byas: On Blue Star is an excellent introduction to the man and his art, and though out of print can be had cheap wherever used albums are bought and sold.

Byas was a one man transition between swing and be-bop, and that means he was never really a be-bop player. Some well-known critics consider his playing on the “I Got Rhythm” track bop, but it isn’t. There are signs that he’s been hearing the bop players use of harmony, but he’s playing within the chords, not extending them up top, and though he’s fast he has the swing quality of hanging slightly behind the beat—the opposite of bop—and his phrasing, the way he connects and accents a series of notes, is also mostly swing with occasional touches of bop.

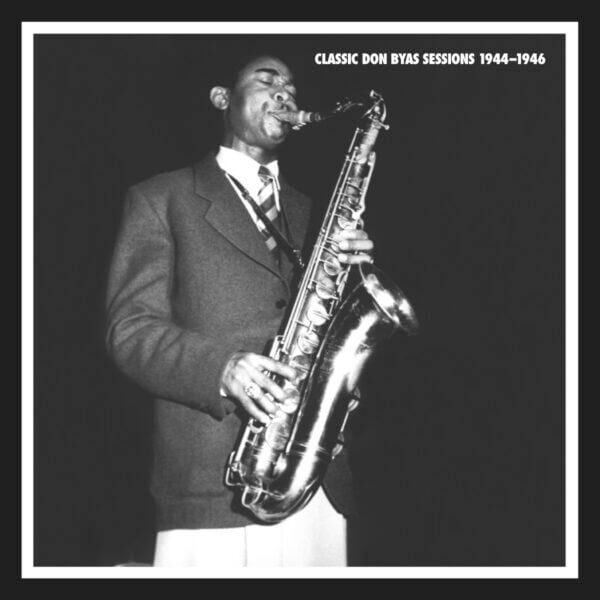

Byas knew bop was happening by the time he hit the Town Hall stage. On the newest archival release from Mosaic Records, Classic Don Byas Sessions 1944-1946, there are 15 tracks where Byas is playing in large and small ensembles that include Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, bassist Oscar Pettiford, and the brilliant and doomed bop baritone saxophonist Serge Chaloff, all musicians who came up playing in swing bands. All the tracks were recorded in January, 1945, and of particular interest are the final three credited to the Dizzy Gillespie Sextet, with Byas joined by tenor player Tommy Young, and pianist Clyde Hart, Pettiford, and drummer Shelly Manne. They play the be-bop staples “Good Bait,” “Salt Peanuts” (credited as “Salted Peanuts”), and “Be-Bop,” and are odd and fascinating for it.

The tracks are a friendly collision between two ideas that at the time had just started to run on parallel tracks and at different speeds. Gillespie and Pettiford are playing bop, everyone else is playing swing, included Manne who at the time was not yet the excellent bop and hard bop drummer he was to become and is awkward as hell, playing swing patterns but seeming to try and dump those and try something new with every beat. It’s something like the famous Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts when Parker appears with swing musicians, but those are jam sessions while these are arrangements meant to be pressed on singles, so the structure shines a bright light on how you’re hearing the past and future superimposed. The misfit doesn’t show a transition but the aftermath, with Gillespie, et al on one side and Byas on the other.

The collection as a whole is a great tribute to a musician who may not be thought of as one of the greats, but was a great player. As Loren Schoenberg writes in the booklet, “Rarely, if ever, has the saxophone ever been played more exquisitely than in the hands of Don Byas.” Schoenberg also points out how the swing musicians created the material that was the foundation for bop, and that Parker was quoted as saying that Byas had played everything there was to play. The set show that all, how Byas set the table for Parker and his associates, and even includes a fantastic little gem, he and Stewart again playing “I Got Rhythmn,” recorded inside someone’s apartment.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.