Gatekeeping gets a bad rap—and it should! Guarding information and experiences to keep them away from people is generally bad. At the very least, it’s a petty and infantile exercising of very limited and temporary power, trying to create an artificial sense of exclusivity and prestige in a pluralistic, democratic culture—snobbery in other words. At worst, you get self-perpetuating, smug Dunning-Kruger disasters, like the American foreign policy consensus of the past sixty years, brought to you by the exclusive club of the Ivy League/centrist think tank/government axis. These are the enemies who guard the gates and exact the price of admission, something often either prohibitive to everyone not born into wealth or simply not available to what the keepers see as the wrong type of person (everyone in the streets of American in late 2002-early 2003 were right about waging war against Iraq, but were scorned by government and the media because they weren’t the right sort of people).

Be clear about these enemies, though, especially because some of them might also be, as an internet wag likes to point out, your faves. What, if anything, are record labels but gatekeepers? There’s nothing pejorative about that—they should be gatekeepers. The whole point of a label is to establish a set of aesthetic values and then record and release music that represents those values. Music that was created in the 20th century, like jazz and rock, is intertwined with some of the great record labels, each of which during their respective heydays had such an identifiable style that the buyer had a good general idea of what to expect from the music even before they brought a new album home and put in on their turntable. Seeing the logo and design of an ECM album fills the mind with crystalline, exacting sound; Capital meant smart, hip adult pop; Elektra/Asylum was the great rock singer/songwriter label; Tommy Boy was the home for pioneering New York City hip-hop.

Arguably the most famous and easily identifiable label of all time is Blue Note. Not only was it the home for hard-bop, the central and enduring jazz movement of the mid-20th century, but it had one of the most famous designs of any commercial product in the last hundred years. Blue Note signifies the best in modern jazz in both sound and look, and through sampling, graphic homages, and plain imitation has been one of the most influential cultural entities ever.

Blue Note’s history as a gatekeeper has meant putting out dozens and dozens of albums that are foundational to jazz and essential to any music library; Thelonious Monk’s first recordings, the bulk of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messenger’s discography—and as offshoots of that band, tremendous albums from Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, and Jackie McLean—Tony Williams’ Life Time, John Coltrane’s Blue Train, Herbie Hancock’s Empyrean Islands, Dexter Gordon’s Go, Grant Green’s Idle Moments, Hank Mobley’s Soul Station, Andrew Hill’s Judgement!, Joe Henderson’s Inner Urge, etc, ad infinitum.

They were also another kind of gatekeeper, recording albums and then, for business or other reasons, putting away the tapes and never releasing them, or doing so only after long delays. That list has substantial things on it, including Sonny Clark’s My Conception (recorded in 1957 and 1959 and released in 1979, sixteen years after Clark’s death), McLean’s Vertigo (recorded in the early ‘60s and released in 1980), and all but one album from the wonderful and doomed tenor saxophonist Tina Brooks.

Brooks recorded five separate albums for Blue Note from 1958 to 1961 (including Street Singer co-led by McLean). His True Blue, a stupendous album that could easily be presented as the single microcosm of the Blue Note sound and quality, didn’t come out until 1980, by which time Brooks had already been dead—a casualty of drugs—for six years. Brooks reputation was rescued and revived by record producer Michael Cuscuna, who in 1985 issued a 4-LP set of his complete recordings via a limited edition box set on the Mosaic Records label. Of the many great services Cuscuna, who died April 20 at age 75, that is the most emblematic. He opened up the gates and presented a great artist to the public. Though the Mosaic set by contract had a limited run, Brooks has remained (mostly) in print since then.

That’s good for jazz. Cuscuna was behind so many other important archival issues, including Herbie Nichols’ Blue Note recordings (also on Mosaic) and the comprehensive Miles Davis collections from his years with Columbia, including the revelatory The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965. Because of Cuscuna, people who love and care for jazz get to experience so much music that would otherwise have been kept from them.

While there may be people with the ability to fill the void that Cuscuna leaves, like Zev Feldman, on the business side the labels have been waging a subtle, but real gatekeeping campaign against jazz listeners (and thus indirectly against the music itself), one that seems inhospitable to openness and accessibility. Vinyl is the fundamental problem, a medium that has been so coveted by people with the money to be collectors—not necessarily lovers—and to afford high end turntable-based audio systems that they don’t mind paying an average price of $30 per LP. That figure came from Billboard in 2022, and greed-flation has only pumped it up from there.

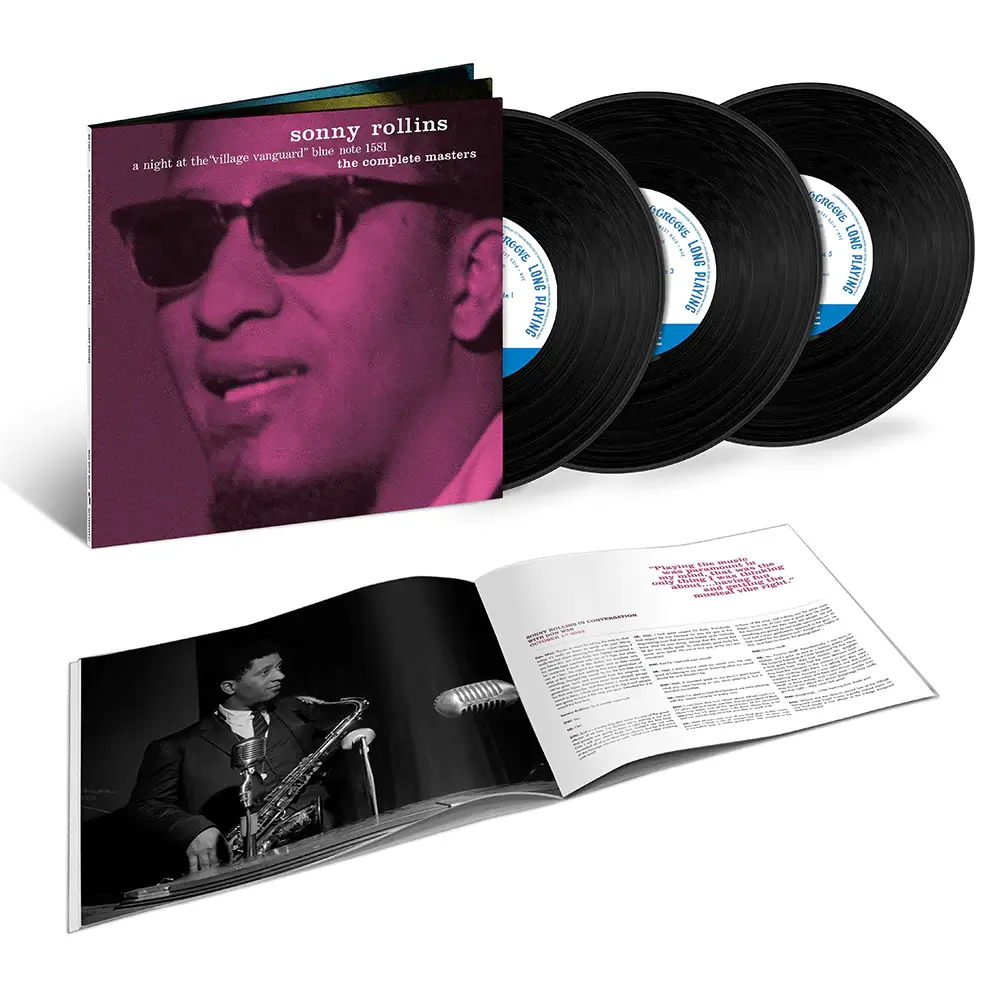

Do you want an LP copy of True Blue? At Blue Note’s own shop, that’s $28, and his other two albums, on their Tone Poet series, are $39 each. The Tone Poet series boasts direct-from-master-tapes mastering and audiophile pressing for the extra cost, and I can say that based on the brand new reissue of Sonny Rollins’ A Night at the Village Vanguard, it is excellent. Although musically phenomenal, the recording quality of those sessions was never good, stuffy in general, flat on the low end and with occluded timbres from bass and drums. The new reissue is better than the previous CDs (and also has the interesting decision of returning to the original album sequence even after the CDs put the tracks in chronological order), there’s much more air around Sonny and when the drums or bass is soloing that sound has much more color. At 3-LPs it’s not cheap but not unreasonable and worth the cost (there’s a 2-CD version as well).

What if you want the fascinating album McLean made with Ornette Coleman, New and Old Gospel, where Ornette plays only trumpet? There’s a specific gate for that, which is the Tone Poet set Ornette Coleman: Round Trip, a box with the six albums Coleman made on the label. Those are good albums, including the live recordings from the Golden Circle in Stockholm, and the underrated, fantastic The Empty Foxhole. But that’s $230, prohibitive to have just one album and as a whole beyond the means of so many people who love this music, including your scribe.

ECM has also gotten in on the trend, with their new Luminescence series which sprinkles out vinyl reissues of their back catalogue (this is all back catalogue stuff, so with only production costs the margins must be attractive). New ones include Jan Gabarek’s Afric Pepperbird (40€) and Keith Jarrett’s Solo-Concerts Bremen/Lausanne (89€). If ECM is seriously looking at monetizing their back catalogue, I humbly request a CD box of Jarrett’s albums as a leader and another that collects his trio recordings with Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette—that would be a service to jazz.

The most egregious gatekeeping comes from Vinyl Me Please, the vinyl subscription service. Now, I don’t have any of these records, and they may sound great, but I can’t afford them—they also duplicate a lot of my library and reinforce the idea that VMP is for newly minted collectors seeking hipness in vinyl. They boast high quality pressings and notes and vinyl color only available from them. A single month (one album), is $46, a year is $435, which comes out to $36.35/album—that’s not a bargain, though it may be a value for people with money because it’s exclusive and they’re willing to pay an extra gate fee for that.

VMP releases can be easy to covet. They have an 11-LP Miles Davis: The Electric Years that haunts my dreams but is also $399 (only $349 if you’ve already paid for a VMP membership) and all the music has already been released more comprehensively and economically by Cuscuna. In late summer, they’re release an 8-LP set of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, the original album plus all the outtakes, a mono mix, sextet tracks, and two live performances. All of this music has been available elsewhere (on more than one label) but not all is currently in print and it’s never been gathered together as a document. Where the Electric Miles box is pure gravy—great fucking gravy—this is an important recording for jazz as an art form. And it’s going to be available to anyone with $399 ($299 if you buy a membership). That’s one hell of a gate.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/