Bad things are just as valuable as good things, at least for a critic. Bad work (art, music, writing) is often a lesson in missed opportunities, the mistakes and missteps that, if corrected, would turn the bad thing into a good thing. It was a bad book I read recently that led to this column, a book about improvisation and the idea of contingency in everyday life that reduced both to the kind of academic detail that may work in a dissertation but that is absolutely not good critical thinking.

Taking random bits of experience and sensation and using them to produce some kind of coherent idea/response is what training in improvisation (and a good liberal arts education) is all about. While neither will make your wealthy or necessarily happy, as Joseph Brodsky pointed out, they both fire up and connect synapses across the brain. And that is how I came to be thinking about jazz, the paintings of Edward Hopper, and the accidentally avant-garde sexploitation movies of Doris Wishman.

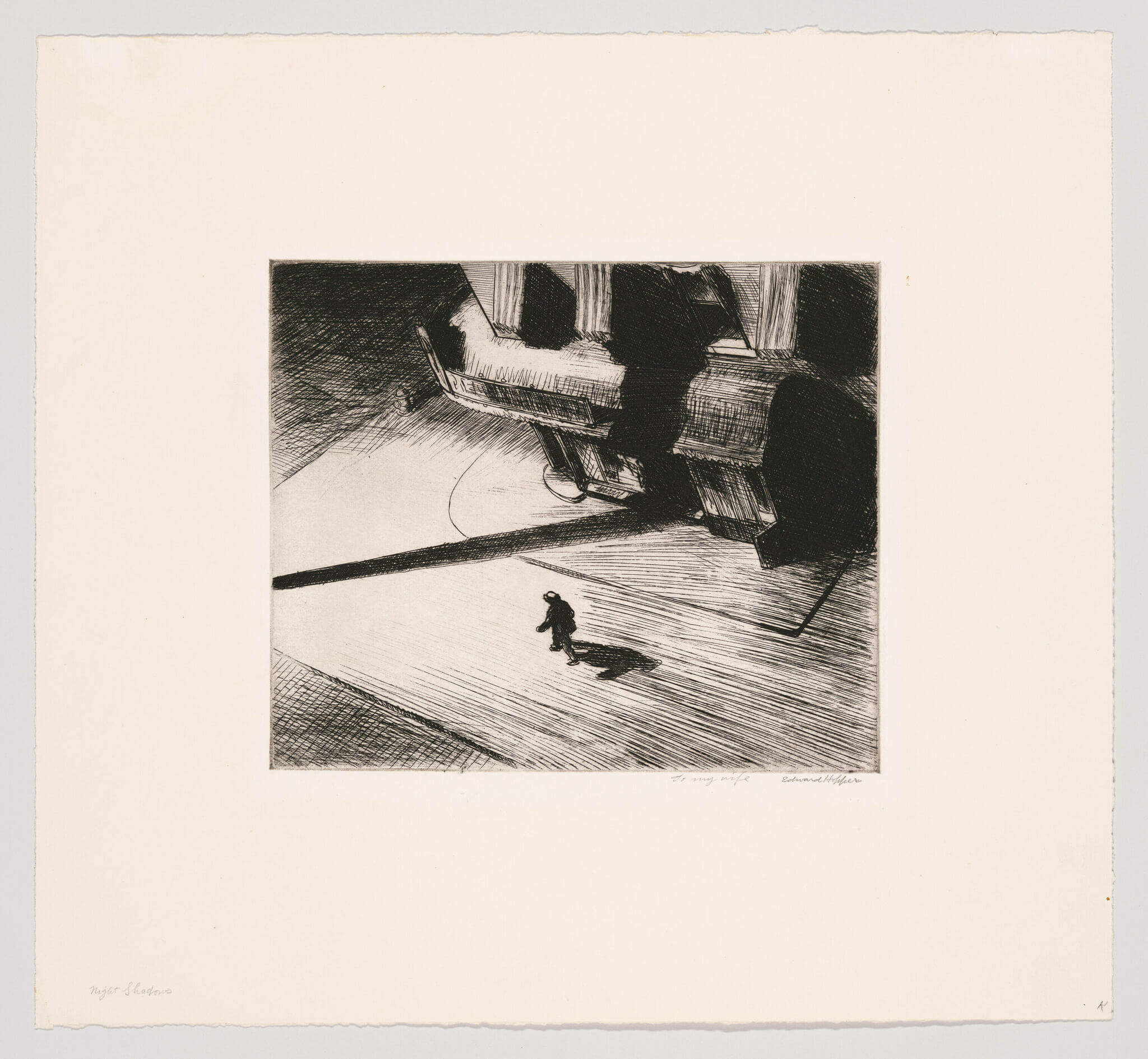

Hopper was not a jazz painter in any way (as opposed to Stuart Davis, as an example), but he was of course one of the great painters of New York City, both the actual place and the one that lives in our imaginations. The recent Edward Hopper’s New York exhibition at the Whitney displayed that, the kind of quiet, lonely corners and empty streets that can be found in the right places at the right times—6 a.m. on an August morning, a theater that has just opened its doors, the noir imagination of Nighthawks (not at the Whitney nor part of the show). And New York is the jazz city, of course, and though the music was not created here, it was quickly adopted and just as quickly centered itself as a progressive style integral to New York City life. All the cats either were here or had to at last pass through here, a poignant example being the late, tragic, problematic Art Pepper. One of the great alto saxophonists, he never played in New York until 1977, five years before his death, when after stints in prison and several comebacks, he finally booked a week at the Village Vanguard. The live recordings show a man more than a little amazed at himself, finally overcoming deep-seated insecurities about being able to measure up as a white musician in the jazz world and being able to headline in the Big Apple.

From Ellington at the Cotton Club, Benny Goodman bringing jazz to Carnegie Hall, Charlie Parker cementing the hyperdrive of America after World War II along 52nd Street, jazz has been the urban, and urbane, sound of sophistication and grit, repose and frenetic rush, the cocktail lounge and the A train barreling express from 59th to 125th street. The noir idea and aesthetic, doomed people struggling for some moral center, thrives in the city, and jazz for decades was the soundtrack for so much noir. It was the music of hip outsiders on both side of the law, and not in any specialized art way—think Peter Gunn and Johnny Staccato, an actual television series starring John Cassavetes as a jazz pianist and private eye. Yeah, television was cool way before The Sopranos.

The sound carried through American popular culture for decades and finding it in some of Doris Wishman’s movies cements jazz as the music of New York. Several of her films were recently collected on the Criterion Channel, and they are riveting. They are intentionally lurid, pressing the edge of what was possible for nudity in the ‘60s. Two striking ones, Bad Girls Go to Hell and Indecent Desires, are noir dramas and what makes them sexploitation is that they are packed with gratuitous nudity. How gratuitous? There’s a scene in Indecent Desires where one of the secondary characters does her “ballet exercises” topless, and it has nothing whatsoever to do with the story or the plot. The thing is, though, that part of the sexploitation is that the movies are full of jazz, which here becomes the music of titillation, desire, and even perversion.

Wishman worked with essentially no budgets, filming with a handheld camera in black and white and without recording audio. She dubbed in all the dialogue in post-production. There’s no natural sound either; there’s dialogue and music that she dropped in after filming. And that music is jazz, and the jazz is meant to signify setting and drama: a character walks down the street, for the moment free and easy, and the music swings brightly; a scene of optimistic preparation has a quirky waltz-time knockoff of “Take Five,” with an alto player imitating Paul Desmond; lurid scenes of sex and violence have the kind of strip club sinuousness in the playing that leads to dissonant chords. It’s a perfect example of how jazz was so prevalent that it could be used in the most unsubtle storytelling because the sheer sound of it was a social cue; it would immediately triggering a sense of context, knowledge, and understanding in the viewer.

It almost goes without saying that these movies take place in New York; in Bad Girls Go to Hell, the main character flees Boston for Manhattan, while Indecent Desires is set in a very recognizable Queens, and specific details of apartment and office life in the borough are essential to the plot. New Yorkers will, and would have, recognized these spaces, and people watching these movies in the ‘60s—or even now—would know by the sound that these are New York spaces. Not Hopper’s of course, but this huge, fantastic city is full of people and stories, eight million as the great noir statement goes, and one sound that connects them all, through every space, is jazz.

Or at least it used to. Popular music has fragmented so much since the ‘60s, and that means New York City sounds have fragmented and, in my view, become elusive. What is the New York sound now, what musicians or bands, in any genre, have a sound that identifies them as part of New York? It’s not clear to me what that might be right now, and even if there is one. My ears tell me that last era of New York City sound was ‘90s hip hop (in a good way), maybe bands like The Strokes (in a not good way). This was my first and last thought while walking through Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars, the great exhibition of Lou Reed’s archives at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Reed, not just in the Velvet Underground but his own solo work, was one of the quintessential New York musicians, and one of the great music makers about New York. Yes, he wrote famous songs about the city, but more than that he captured that New York City sound, one that goes across all styles. It’s tight at the core but loose, jangly, even a little spiky on top, has an attitude but isn’t mad—as the cliché goes, West Coast people act nice but are mean, while New Yorkers act mean but are nice. So, the music confronts you a little upfront, but it always buys you a shot and a beer in the end. It’s fundamentally mature, and in a pop landscape that focuses almost exclusively on ephemeral juvenilia of one kind or another, where Taylor Swift has ridden the long YA fiction wave to help supposed adults feel like they never left college, it’s hard to find mature music out there. That’s the New York sound, made by and meant for people who have their shit together, no matter their age.

Author

-

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/

View all posts

George Grella wrote the book on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. He write other stuff too. killyridols.substack.com/