While many Brooklynites associate Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest or fireworks with the Fourth of July, the holiday is also an opportunity to celebrate Fort Defiance.

The solid land we know as Red Hook was once pretty much a swamp. In the 1630s Dutch settled in the area and began to turn the marshes into farmland. When the Revolutionary War began, the land was still different than it is today.

With fighting already underway in 1776, New York City, specifically Manhattan, was a target for the British, and in response, Washington’s trusted advisor, General Nathanael Greene was given the job of buildings forts in Brooklyn in preparation of a Long Island military campaign.

“Fort Greene was at the furthest point to the east,” wrote Suzanne Spellen in a piece for the Brownstoner. “Other forts were planned on down through the Heights, with walls and fortifications built in several places in the Heights and in Cobble Hill. The westernmost fort would be in Red Hook. It was called Fort Defiance.”

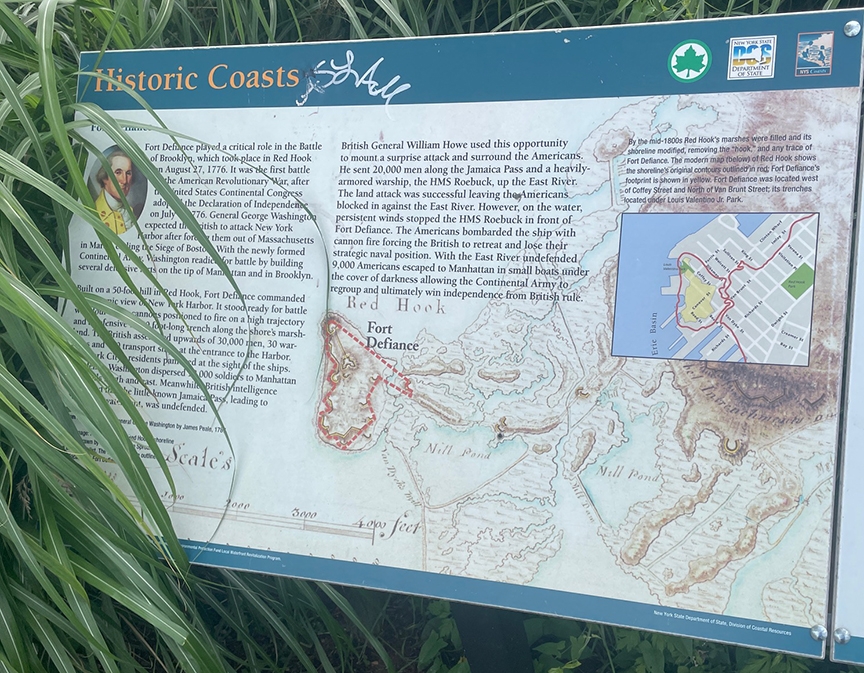

Fort Defiance was built on the waterfront with a clear view of New York Harbor. It’s exact location has been contested (see accompanying story) but it is remembered locally with in Valentino Pier Park. A plaque there states that the fort included “four heavy cannons and a 1,600-foot-long trench along the harbor’s shoreline.”

“A few days after the Declaration of Independence British ships, the Phoenix and the Rose sailed from Staten Island, heading up to the Hudson River,” says redhookwaterfront.com. “The cannon at Fort Defiance opened fire, as did the cannon from Governor’s Island and Fort George. They damaged the ships, which still made their way to Tarrytown, at the Hudson’s widest point, where they attempted to blockade supplies to the city. The ships returned to Staten Island a month later in preparation for what could have been the only large battle of the war.”

In August of 1776, more than 30,000 British troops gathered at the entrance of the harbor, including 30 warships and 400 transport ships. After seeing the ships, many New York City residents panicked, and in response, George Washington sent 18,000 soldiers to Manhattan and lands north and east.

On August 27, 1776, the British responded by launching a surprise attack led by General William Howe after they discovered that the Jamaica Pass (which led to Brooklyn’s waterfront) was undefended. Howe sent the warship, the HMS Roebuck up the East River and sent 20,000 troops along the Jamaica Pass. While the land attack was successful, strong winds helped stop the HMS Roebuck in front of Fort Defiance.

“The Americans bombarded the ship with cannon fire forcing the British to retreat and lose their strategic naval position,” the plaque says. “With the East River undefended 9,000 Americans escaped to Manhattan in small boats under the cover of darkness allowing the Continental Army to regroup and ultimately win independence from British rule.”

Though the HMS Roebuck was stalled, the British were still firing at the American troops from the ship at close range and while the Americans were able to force the ship to retreat, there was also a lot of damage to Fort Defiance. The fort was built back up but was abandoned after the war ended in 1783.

“The earthworks were allowed to settle, and land dredged to form the Atlantic Basin helped even out and fill in the ponds and streams,” Spellen wrote. “By the mid-19th century, Red Hook was beginning its journey to becoming the largest and most important port in New York.”

Now, in recent years there have been some debates about the exact location of Fort Defiance in Red Hook.

“For many years, historians were remarkably consistent in recording the Fort as having been in the approximate location of the intersection of Van Dyke and Conover Streets,” wrote Connor Eugene Gaudet in a 2015 Star-Revue story. “These include men who were writing when the Revolutionary War was still within living memory or just a generation or so out of it in the 1850s and 60s.

“However, for some reason in the middle of the 20th century, people started recording the location as having been at Dwight and Beard Streets. The change occurred quietly, but it nonetheless occurred, and most books written between 1950 and 2010 are consistent in recording that as the Fort’s location.”

Historian James Kelly placed a bronze plaque at the Todd Shipyards Corporation, at the corner of Dwight and Beard Streets in 1952. Gaudet questioned whether the motive behind the plaque being placed there had to do with the Todd Shipyards Corporation paying for it, even if it was not where Fort Defiance was actually located.

“The plaque itself disappeared many years ago, but its legacy has remained in the false impression it left about the fort’s location,” wrote Gaudet. “A new plaque was created in 2012 and placed in Valentino Park, much closer to the actual location of the fort it commemorates.”

It is nice to have the plaque in Valentino Pier Park although the plants around it are overgrown and make it tough to spot. Like the plaque, Fort Defiance is easily overlooked but it was pivotal in the Battle of Brooklyn. Fort Defiance may be long gone, but the Fourth of July is the perfect time to celebrate it and acknowledge its importance in the United States breaking free from the British.