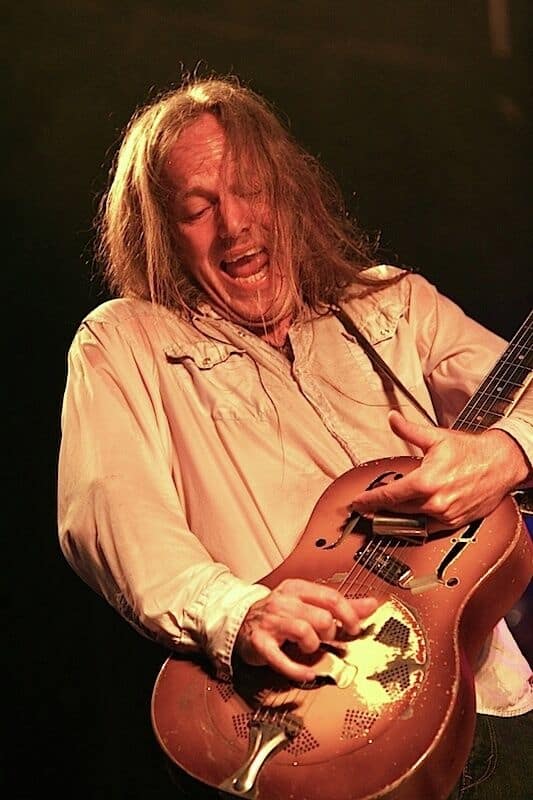

The first time I saw Hugh Pool perform, I was deep in conversation with an old friend, Tom Vaught, at the enchanting but since departed Lakeside Lounge. Suddenly from the stage, a long-haired, National guitar-picking, slide-screaming, harmonica-through-amplifier, screeching force came soaring like a nip-soaked cat on fire in a bag filled with rabid dogs on acid. Our jaws became acquainted with the floor tile. We felt it in the air; this night had magic in it. We got in close and gave this man our full attention. We were thoroughly inspired, aligned, and ready for a night of enchanting debauchery.

After Hugh finished his show, we sat down with him and introduced ourselves. Tom duly impressed Hugh with his eclectic tales of nightlife, one involved an alley, a mobster and a meatball sandwich available, if you “was from the neighborhood” of Little Italy. Hugh was hardly shy and added a few reports himself, painted with sharp wit and a wizardry of wordplay.

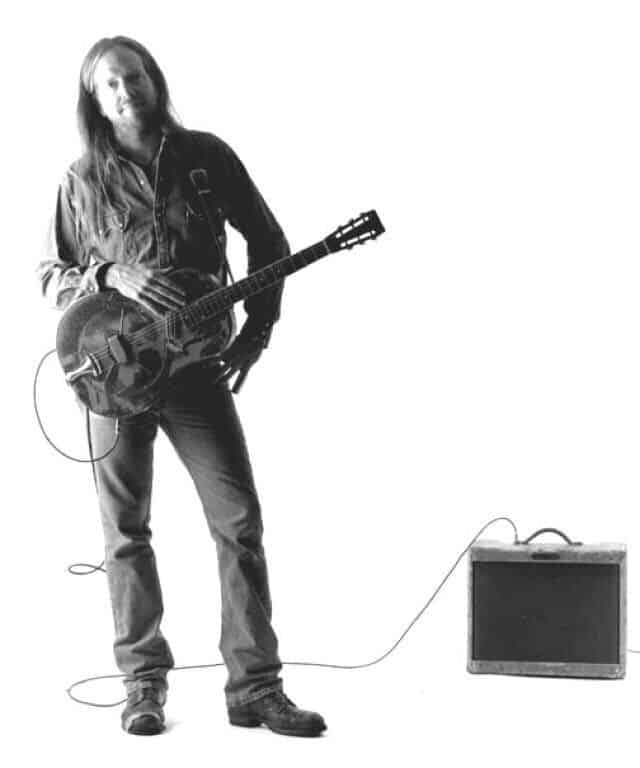

Hugh Pool, born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, came to New York at 20 years old to see where his music would bring him. Cut to 2019, Hugh Pool is married with two kids and owns a house in Brooklyn and a long-established recording studio, Excello Recording. He has had years of bounty, struggle and everything in between, yet he has always managed to keep himself and his family above water as a musician and studio owner in a century that has created far too many obstacles toward obtaining that goal.

Hugh Pool, born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, came to New York at 20 years old to see where his music would bring him. Cut to 2019, Hugh Pool is married with two kids and owns a house in Brooklyn and a long-established recording studio, Excello Recording. He has had years of bounty, struggle and everything in between, yet he has always managed to keep himself and his family above water as a musician and studio owner in a century that has created far too many obstacles toward obtaining that goal.

Hugh Pool is not only a gentleman; he is a hero and a legend in New York, a city that could try shifting its focus back to all of the genuine music it has helped inspire the past few hundred years and cease from creating half-baked celebrities or phone zombies simply observing and not participating in what this paradise has to offer.

I asked Hugh a few questions as he was mixing a Reverend Freakchild album and readying to play his 11th St. Bar residency:

JG: Have you ever tried to get out of the music business?

HP: I’ve done nothing more than fantasize about it. I’ve wondered what I might have accomplished in another field had I put as much time, money and energy into it, but at the same time, I also realize that I’ve been very lucky to co-create the life I have and in the middle of my third decade and do what I do “professionally.” I still consider myself a lifer. I say co-create because there is too much luck, generosity and fate involved to believe that you created anything in life yourself.

JG: If a twenty-year-old guitar-slinging singer just arrived to New York City in 2020, how could one possibly begin to build a life of home, recording studio and family as you have in Brooklyn?

HP: With substantially more help than I received. I think about this question with regard to the many 20-year-old interns I’ve had at the studio over the years.

The cost of housing, going out with friends, a cell phone bill, an internet connection; the baseline expectation and associated expenses feel very different to me. When I was 20 in 1985, the golden years of the modern art era were still glowing here in New York and it was still very bohemian. You’d see pictures of David Byrne wearing black espadrilles which cost 2 bucks in Chinatown and Phillip Glass would be walking down Great Jones street wearing an Army surplus jacket and jump boots from a second hand shop. You could look like that for 20 bucks.

There is a part of growing that is emulating. You try shit on and kinda keep what fits and recycle what doesn’t. This is as true of clothing as it is of other elements of the creative style. Nurturing or growing that creativity requires experimentation and ideally (when you are young) you get to experiment without big risk. Higher monthly costs significantly increase the risk, and I wonder how the army coming up to replace us here deals with it internally.

To me that creativity was the lifeblood of New York. I never would have moved here if I were not drawn by generations of artists. Walt Whitman, Willem de Kooning, Allen Ginsburg, Saul Bellow, Bob Dylan, the Ramones, Blondie, the Talking Heads and the gigantic history of Greenwich Village, Folk City, and Dave Van Ronk. I mean, I know New York is the financial center and real estate, blah, blah, blah, but that never entered my mind as a kid. I moved here with $300 to try and be part of the creative bloodstream. I don’t know what that feels like today but I know that people are finding a way.

JG: Can you recall one the worst gigs you ever played in New York?

HP: My worst gig was the gig when I realized that my feet hurt. When it happened, I was playing guitar with another artist, in a short-lived club in midtown. I remember thinking about how in all the years that I’ve been playing I had played with broken ribs, stitches in my mouth, high fevers, outdoors in December in Sweden, etc., but never until that moment had I ever backed away from the performing moment enough to realize that I was uncomfortable. I thought to myself, oh… maybe this gig sucks. That felt valid because I was already in my 30s at this point.

JG: Do you consider yourself a Brooklynite at this point?

HP: I consider myself a Greenpointer because we are pretty involved with the community over here and that is a good thing, totally driven by Janie. My kids are products of our home, this community and our local public schools so I’d have to be pretty aloof not to consider myself a Brooklynite. Especially on account of the fact that my kids are kind, bright, well-mannered and energetic people.

They have good internal compasses, and that stuff is not all stuck inside them by Janie and myself. That stuff is stuck inside them because of what they see and experience. They are born in Brooklyn! I’m a Pennsylvania transplant grateful for my new home but my kids are Brooklynites.

JG: Have you ever considered going back to Pennsylvania or leaving New York City?

HP: Yes… several times a year.

JG: What was the busiest year at Excello like for you?

HP: Early 2000s. 2003-04 or something. A bunch of stuff happened at the same time. Our managing partner left the studio partnership, an article about me came out in Tape Op magazine and an engineer-producer I was good pals with was heating up a bit in the biz. The studio was a one-man show for a couple of years.

I was doing every session, the accounting, fixing headphones, managing the bookings and logistics. I’d just bought a house and had a new kid in the mix too. Plus I was playing 10 nights a month. It was pretty intense but perfect timing. You can handle all that shit no problem when you’re in your 30s or early 40’s.

JG: Did you ever dislike a band’s music that you were recording so badly that it affected the sessions?

HP: I have always been of the opinion that it’s my responsibility to find the thing in what someone does and do my best to make it beautiful… or make it ugly… just make it say something worth saying. So no, I find that thing.

I feel it’s my job and I have to do my job well or I don’t do well internally.

JG: If you were never a musician, engineer or anything in the music industry, what kind of job could you have seen yourself doing?

HP: First, I wanted to be a salvage diver, then a downhill skier, then a musician and now I guess anything that puts several million dollars into your bank account… you know, same as any other American.

JG: Do you still practice guitar?

HP: I most certainly do. I wish that I were more consistent about it but there is always a guitar nearby. I take one on every family trip.

I’m never without a guitar, pad and paper. Never.

JG: Did you grow up listening to a lot of slide guitar players?

HP: Not especially slide players. I listened to the radio: Dr. Hook, David Essex, Brewer and Shipley, Motown, etc., and then Neil Young and then Allman Brothers. That’s when I first heard slide and from there, through the Grateful Dead and Hot Tuna directly the world of the blues and then the extremely profitable sub-genre of acoustic blues and bottleneck guitar.

JG: How would you like to see yourself 20 years from now?

HP: Well, alive for one thing and maybe with some grandkids and kids who are happy and reasonably secure. I’d like to feel that I’ve done my family proud and helped a lot of people.

I still very much hope that I can increase my media capacity, perform and pull attendance to larger venues with larger paydays and work with artists on similar lines, but if I had to choose, I’d definitely trade the professional stuff for the personal stuff.