Everyone knows Jimmy Stewart couldn’t ever play anything but Jimmy Stewart. He never lost the mid-Pennsylvania drawl that’s given rise to thousands of impressions, poor and expert alike (mine’s alright, but see Dana Carvey for a particularly good one). And his narrow, six-foot-three frame lent him a loping, awkward on-screen presence that is a far cry from the preternatural wit of Cary Grant or laconic machismo of John Wayne. But the dead giveaway for the classic Stewart role is decency and earnestness.

The one good guy, trying to do the one good thing – damn the odds. Driven into a corner by the less principled, Stewart’s characters give the audience nothing less than total moral righteousness, usually culminating in a stammering, furious speech. Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939) and It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) are the obvious examples of this formula. But others, like Henry Hathaway’s 1949 documentary-style noir Call Northside 777, also showcase this common-yet-exceptional rectitude.

It’s commonplace now to say that Stewart’s four-film run with Alfred Hitchcock is the actor’s most important turn away from this formula. Films like Rear Window and Vertigo refashion the beloved American everyman as a voyeur and pervert, twisting our sense of familiarity into shock. But the legacy of these late-career films with the Master of Suspense underplays Stewart’s eight-film collaboration with Anthony Mann through the 1950s, which resulted in a spate of darkly brilliant Westerns, including 1950’s Winchester ‘73 and The Naked Spur three years later.

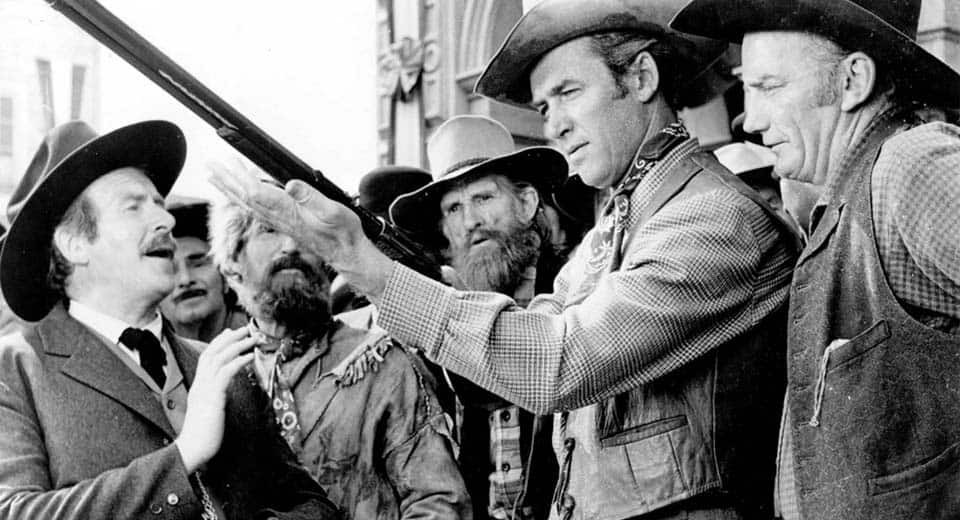

Winchester tells the story of Lin McAdam (Stewart) and his old war buddy ‘High-Spade’ Frankie Wilson (Millard Mitchell) as they hunt outlaw Dutch Henry Brown over a personal feud involving the murder of their shared mentor (details remain hazy until a final gunfight). The film opens in Dodge City at a Centennial sharpshooting competition, Lin knowing that Dutch can’t resist the prize: a special “one in one thousand” version of the film’s namesake rifle.

The gun functions as a formal plot device, driving men wild with envy and changing hands between Lin, Dutch, a Native American chief (Rock Hudson) and others in a sort of Brotherhood of the Traveling Repeater. But it fortunately never becomes a gimmick, because Stewart’s uncharacteristic callousness and violence give the film its surprising emotional core.

At the time of release, Winchester was certainly Stewart’s most violent role. In one scene, he chokes out the fastest gun in Texas on a whisky-soaked bar counter. In another he puts his expertise fighting for the Confederacy to use, helping a stranded cavalry unit annihilate an attacking band of Native Americans. Speaking through High-Spade, the film asks again and again if any of the violence set in motion by the quest is really worth it, especially when it’s all just to kill another man.

Mann casts Stewart as a veteran again in Spur, and to great effect. Channeling his wartime experience as a bomber pilot, Stewart plays Howard Kemp, a reluctant killer on the hunt for the $5,000 bounty on marshal-killer Ben Vandergroat somewhere in the Rockies. Along the way he picks up two partners who elect to split the reward in thirds, with Millard Mitchell this time playing an unlucky prospector alongside a rakish ex-cavalry lieutenant. Janet Leigh also appears as the daughter of a slain outlaw.

Where Winchester contrasts the path of a sought-after object with a man’s personal crusade, Spur goes further. How impersonal is it to kill a man just for the price on his head? Howard’s reasons for doing so certainly are personal: he gave his ranch to his wife when he left to fight for the Union, and returned to find that she had sold it and ditched him for another guy. He’s so tortured by it that he wakes the group screaming in the night. Getting the $5,000 is just enough to buy back the ranch.

Again, it’s Stewart’s signature decency that undergirds Mann’s film. How can our Jimmy be so mean? The film tests that decency, asking how far Howard can go. In a sequence near the end of the film, the band faces the choice of attempting to cross a raging river or taking a five-day detour. The discharged lieutenant, placing a noose around the outlaw’s neck, urges Howard to drag him through the rapids.

“He’s not a man, he’s a sack of money. That’s why we’re all here. Especially you.”

Both Dutch and Ben are killed eventually, slung up on the back of a horse by Jimmy Stewart. And while in Winchester he hangs his head and embraces his woman until the black-and-white fades out, in Spur he tearfully tries to convince Leigh that he’s no good. He can’t, of course.

Winchester ‘73 and The Naked Spur, and many other Mann-Stewart collaborations, are available to rent on Amazon Prime Video, iTunes and other streaming services.