I recall when a very young lad around 5 years of age living at 113 Bush Street in 1934-35. It was truly a slum tenement type building, cold water, and toilets in the hallway. Heat was made by the occupants using wood fires in a cast iron kitchen stove. The people on Bush Street were tough as nails, worked at odd jobs, anything to put together some food for the kids at a time when jobs were unheard of.

The resilience of these people was astonishing, although at my age I hardly noticed it. But today I can look back and see the determination embedded in their faces and in their hearts, not to let their problems overcome them or deter them from striving to survive. True Red Hookers, never giving up despite the abysmal conditions they were forced to endure. Real John Wayne style “True Grit” you might call it.

Not surprisingly, there were no people from Red Hook living in Hoover City. They were a fiercely proud people who never could surrender their dignity because of hard times.

Bush Street between Clinton and Hicks street was the very last row of houses facing south towards the grain elevator, this imposing structure had been built around the mid 1800s and used for unloading grain ships. This was the major activity on the Red Hook waterfront for over 100 years. Annually, more grain was shipped from Red Hook by sailing vessels as well as steamships during that period than any other place in the world.

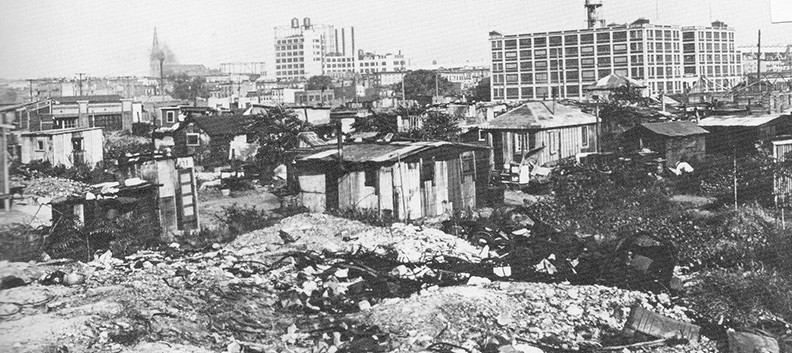

Looking south towards the water and the grain elevator structure from Bush Street we view two huge tin lots approximately a double city lot each in size. Both existed as dumping grounds for the rest of New York City. As children we would play in both of these lots. There were many truck tires, of the solid rubber type – balloon tires having not been invented at that time. The parallel streets opposite Bush street were first Lorraine Street and then Bay street in that order

As kids, we called them “the tin lots” and played in the abandoned huts built by the occupants of Hoover City. All three streets, Bush – Lorraine – and Bay streets were bounded by Court Street on the east, and Hicks St. on the west. And therein was the boundary of Red Hook’s Hoover City as I recollect. After Bay Street South, was water, now filled in. This was around 1934/35, so a good deal of the homeless haven was abandoned or evicted, and work opportunities started to increase as New Deal programs helped boost the Depression economy.

The prime occupants of Hoover City in Red Hook were merchant seamen who lost their positions aboard the ships that came to Brooklyn from various foreign nations. These shipping companies could not afford to hire the manpower needed to return home with the cargo so they cut costs by sailing shorthanded. They virtually abandoned hundreds of men every time they set sail, creating a mass of hard working men with no jobs and no place to stay. And even worse, no money. Those who were abandoned chose instead to convert the tin and other waste found in these lots to livable housing. If you can call no water or toilet facilities livable. They did so in order to be close to possible sailing employment. They were intelligent, honest and law abiding people. Some had wives and children, others single, and they all respected each other despite their dire situation. At the beginning of the Great Depression there were many “Hoovervilles” or “Hoover Cities” across the country. In Chicago for instance there were many unemployed stockyard workers existing in Hoover City type compounds.

I am informed by Mr. Lars Nilsen who heads the Norwegian Immigration Society, that he has records of nearly 800 Norwegian Seamen who were forced to endure those miserable conditions of Hoover City in Red Hook because of their lost work in the shipping industry. Most of these men had families back home yet no way could they reach them. A Norwegian Church on Summit St did their best to assist these men, and local food merchants donated food. Local churches rendered assistance also, but the Norwegian Salvation Army, and Norwegian Seamen’s Institute predominated in their efforts to render aid and comfort to these abandoned men. Many, if not all of the Norwegians ended up living in Brooklyn permanently and migrated to the Bay Ridge area.

It’s also safe to say nearly everyone looked upon their plight with pity, even the residents of those slums on Bush Street I mentioned earlier where I lived as a young lad.

I nearly forgot to relate a now comical story about when I lived in 113 Bush Street. It was a heck of a cold winter night and everyone was roused from their sleep by a crashing noise in the slum buildings hallway. It seems a squatter on the top floor was cold, so he decided to take an axe and chop up the banister for his firewood to keep him warm. All the regular building occupants banded together and wasted no time in evicting this squatter along with his axe and anything else he wanted to take along, but no firewood. I’m sure those good people would have loved to burn that wood in their stoves, but no one dared touch it.

If there’s a moral to this story, it must be this – when walking the streets of NYC today, if you come across a homeless person covered with newspapers or cardboard to ward off the cold, don’t cringe at the sight, or turn your head and pretend they do not exist. At the very least, look to the heavens and say “There but for the grace of GOD go I.” Or perhaps you can reach in your pocket and come up with a buck or two?

Discover more from Red Hook Star-Revue

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

7 Comments

Years ago in the 20 and 30s my Mom lived on Bush at one time. She told me about Hoover City. She also said that they moved often because they would get one free month and a painted apt. My grandfather and Uncle owned a bar on Lorraine St. called Curry Tavern.

Do you know if its possible to search for the name of my grandgrand father among those 800 Norwegian Seamen who were forced to endure those miserable conditions of Hoover City in Red Hook ? I have reason to belive he could be there.

My guess is to ask this organization… https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwegian_Seamen%27s_Church,_New_York

There are church’s on Staten Island built by those Norwegian sailors. What is remarkable is that the ceilings, which were beautifully built, were sailing ships turned upside down.

I lived in Red Hook from the early 1940s until the 1963. We lived in the “point”, on Walcott Street, two blocks from the docks. My Mother lived there almost all of her life, starting in 1905. We too lived lived in a cold water flat. A pot belly stove in the celler supplied the hot water. When the ” New Deal” came along, my dad got a job with the “WPA” and on the docks as a Stevedore, working as much as twenty hours a day. Other than Joey “Ambers” the neighborhood bookie, there was no crime. The men in the neighborhood saw to that. I moved to Staten Island when they built the Verrazano bridge.

Thanks Tony. If you ever want to send us an article about growing up in Red Hook, we’d be happy to publish it. In the meantime, here is a book just published that I recommend… http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1400067278/ref=s9_simh_gw_g14_i1_r?ie=UTF8&fpl=fresh&pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_s=desktop-1&pf_rd_r=03FKQ4DFH6V55J0JQZ6N&pf_rd_t=36701&pf_rd_p=2079475242&pf_rd_i=desktop

Tony Caputo, you mentioned Joey Ambers and that brought back memories of the times I drove my Dad down the point to see him. My father also spent a lot of time at the Post since he was a WW2 veteran that was a little famous in the neighborhood due to his friendship with Audie Murphy, e and my dad were in battle together and each took turns at saving one another’s ass. He was know as on Court St and the Point as Andy Gump.