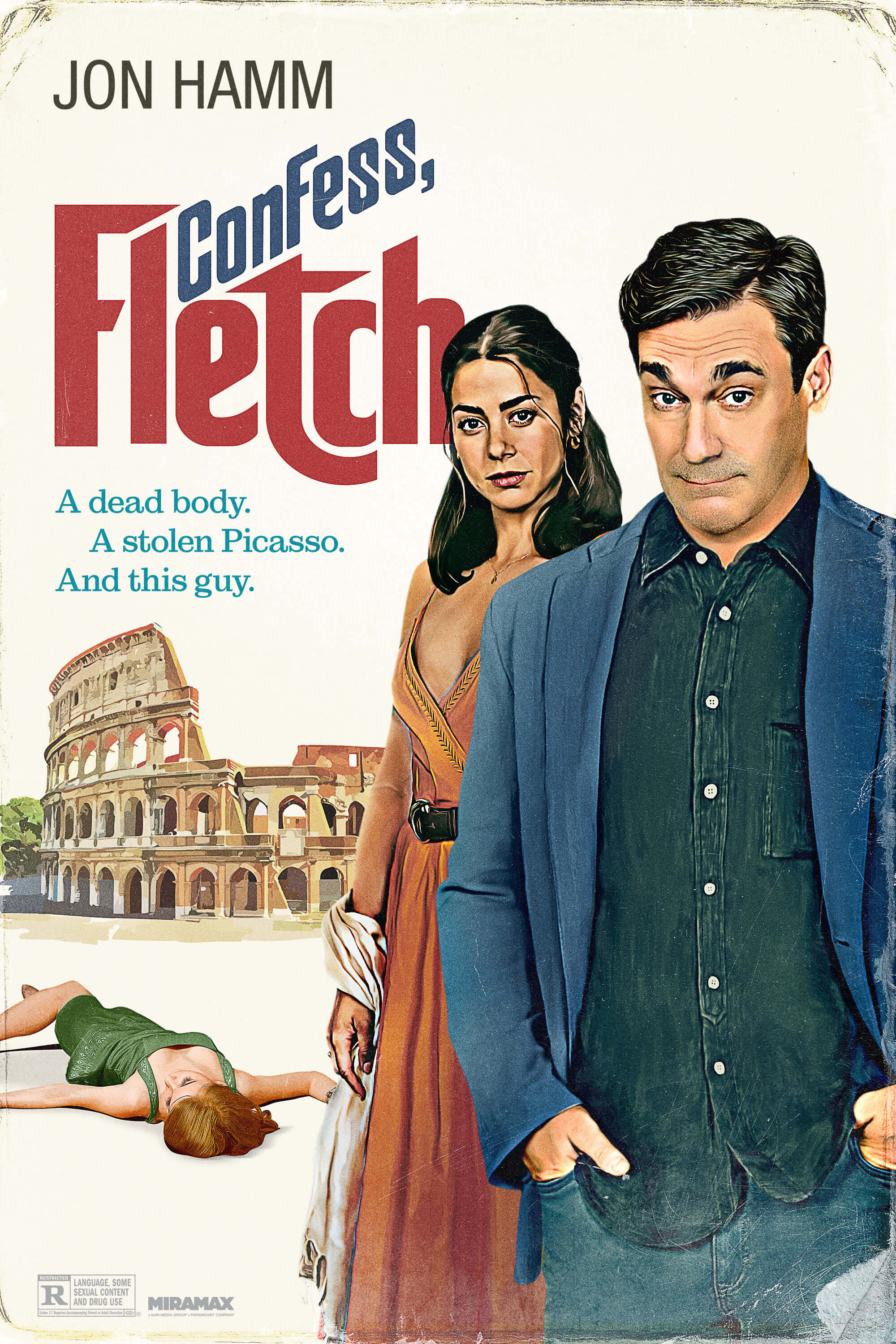

Let’s talk about some recent movies! I’ll start: Confess, Fletch. It’s pretty fun, a decades-in-the-making reboot of Chevy Chase’s 1980s comedy-mystery franchise based on Gregory McDonald’s series of novels, with Jon Hamm in the role as investigative reporter-turned-amateur-gumshoe I.M. Fletcher. It’s a solid effort from director and co-writer Greg Mottola, albeit a bit too shaggy and padded out to meet its 98-minute runtime. But it’s the kind of irreverent mid-budget flick Hollywood doesn’t make much anymore. And it benefits from a stacked cast that includes Kyle MacLachlan, Marcia Gay Harden, Roy Wood Jr., Lorenza Izzo, and John Slattery, who absolutely steals the movie in his handful of scenes. Who can resist a Don Draper-Roger Sterling reunion, and on the big screen no less?

What’s that? You haven’t heard of Confess, Fletch? You’ve never seen a poster or a trailer or an ad or anything?

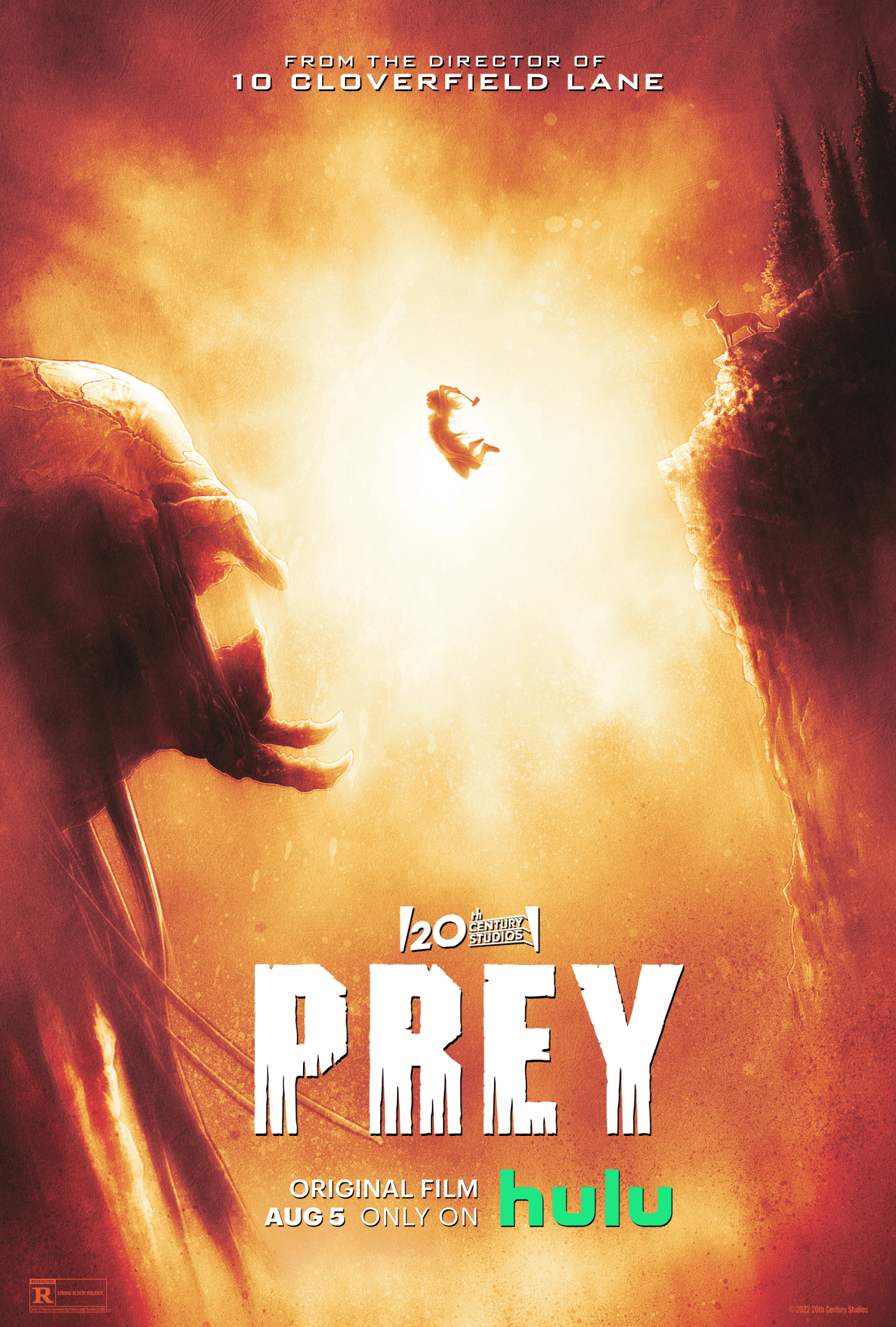

- What about Prey? Surely a new Predator movie is big enough to have crossed your… Oh. Nothing there either.

No, no, it’s fine — I’m confused, too. But it’s not you; it’s Hollywood. Because it seems that the mainstream movie industry has lost interest in making movies.

Confess, Fletch was unceremoniously released in 516 theaters on September 16 and basically out of 516 theaters two weeks later, with a paltry $532,000 box office to show for it. It was, however, dumped the same day on streaming services, where you can rent it for $19.99.

Prey fared even worse. A Fox picture via Disney, which got Predator in the acquisition deal for X-Men, Prey couldn’t even make it onto Disney+. It was slid instead onto the Mouse’s second-tier streaming service, Hulu. I guess no one wanted kids to accidentally stumble on an alien ripping out someone’s spine when all they were doing was looking for the latest episodes of Bluey.

On paper, both films should have been locks for extended multiplex runs. They’re entries in established franchises; they got decent-to-solid pre-release buzz; and they’re showcases for a charismatic star (Hamm in Fletch) and creative extensions of known universes (Prey). They even got fairly positive-to-gushing coverage after their releases. None of it was enough. They were treated like cultural carrion, left to fester in the tepid feeds of their respected streaming services.

And for what? I’m not sure if you’ve looked at Fandango lately, but multiplexes aren’t exactly hotbeds of new films. Look at what’s playing at a theater near you — if you still have a theater near you — and you’ll see months-old Marvel films and re-releases of years-old blockbusters like Avatar, and, um, Jaws for some reason. There are smaller movies, like Everything Everywhere All At Once or Bodies Bodies Bodies, but none are mainstream crowd pleasers, nor are they from the major studios. Surely there are business considerations at play here, with AMC and Alamo Drafthouse committing X number of screens to Thor 4 for Y amount of weeks, full stop.

But there seems to be something else happening: Hollywood in something close to a meltdown.

For all the bloviating about liberal La La Land, the movie industry has always been a fairly conservative business. Major studios and exhibitors respond slowly, if at all, to systemic changes, and they take defensive, victimized postures when confronted with challenges. It happened in the 1950s with television, the ‘80s with VHS, and today with the assault from Netflix, et. al. Does it matter that the power of streaming is being revealed as a mirage as Netflix’s market cap sinks like a stone? Not a lick.

Like the rest of the American economy, megamerged corporations posing as film studios and the AMC-Regal multiplex oligopoly only care about quarterly results. And, thanks to the pandemic, business has been very, very bad. In the accepted narrative, audiences stayed home — so they wouldn’t die; the selfish bastards — and discovered their insane home theater setups are perfect for streaming movies and avoiding not only viruses but the double-dipping price gouging they experience when they buy tickets then concessions at their local 10-screen.

But rather than make a play to get audiences back into theaters — in capitalism known as a market correction — studios and theater owners chose to rend their garments and play the victim. They’ve triple-downed on the worst kind of spectacle, completely jettisoned adult audiences, and placed all their bets on one or two super-tentpoles, be it Spider-Man: No Way Home in 2021 or Black Panther: Wakanda Forever this year. The result has been a very strange, completely unbalanced, and arguably unhinged mainstream moviegoing experience. New studio product gets made, but it’s almost entirely big-budget franchise blockbusters, like Thor: Love and Thunder and Dr. Strange In the Multiverse of Madness and Jurassic World Dominion and The Batman. Beyond that, there’s little else coming out of the studios. Warner Bros. has a modest rubbernecking hit in the tabloid-clickbait Olivia Wilde film Don’t Worry Darling, and Universal continued cashing in on Jordan Peele with Nope, but those are decidedly outliers. Original scripts like The Whale and awards-bait non-franchise films like Blonde are coming, as they have for the last few years, from tasteful indie studio-slash-subcultural-tastemaker A24 or, more relevant to this conversation, Netflix.

Again, Hollywood could market-correct. In the past, if some economic measure found audiences flocking to a typical kind of film, studios would rush a bunch of copycats into production. Not in 2022. Rather than adjust their business, they’ve shifted blame. It’s not their fault the industry is cratering, it’s the audience’s. They won’t come back! They’d rather be streaming! They hate movies! They’re selfish! They don’t respect filmmaking! They don’t understand!

Besides the fact that it’s not moviegoers’ role to prop up a failing, flailing industry, it’s not our fault. Confess, Fletch and Prey got some good attention, which might lead to sequels — which will go straight to streaming. Because that’s where the real money is. Why hope for a one-time ticket sale when you can reliably pinch the suckers for a monthly subscription? Hollywood wants us to stream, but when it doesn’t put anything worth seeing in theaters it brays about how audiences are killing moviegoing.

Sorry, but you don’t get to have it both ways. People who like movies, generally, like watching movies with other people (particularly comedies and horror). It’s a communal art, at its best when we’re watching together. Streaming is fine, but it’s antiseptic and a poor replacement for the act of moviegoing. The wild success of Top Gun: Maverick — yes, admittedly a sequel — proves that people want to go to the movies. But only if there’s something to see, and only if they know it’s coming to a theater near them.

Put stuff in theaters, tell people about it — I’m not an MBA, but that seems like a solid foundation for a functioning movie business. But the industry has chosen to cast audiences as villains in its poor-little-billionaire act, the kind of virulently classist canard deployed by people like Mayor Eric Adams when discussing the state of New York City’s economy. (It’s tanking because spoiled white-collar millennials won’t get out of their pajamas and go back to the office; it has absolutely nothing to do with developers and executives, the people with capital and means, refusing to evolve.)

This kind of full embrace of victimhood is the worst kind of punching down. And it’s deliberately obfuscating.

Let’s go back to 2019 — the year everyone with money agrees was civilization’s apex — and revisit The Irishman. Martin Scorsese’s three-and-a-half-hour gangster epic was the stuff studios and theaters salivate over: Scorsese back to making a mob movie; one that starred Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, no less, who share the screen a lot; and the director lured Joe Pesci out of retirement, so it’s also a kind of Goodfellas reunion. Who could refuse that offer? Paramount, it turns out, which balked at a nine-figure budget driven up by groundbreaking de-aging technology. Netflix stepped in, got Scorsese the money, and we were all treated to one of the finest films of the decade. (History will prove me right on this.) But you know who wasn’t happy? The National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO), which refused to book The Irishman when it couldn’t coerce Netflix to extend the film’s theater-exclusivity window before it hit streaming.

The Irishman made $969,000 at the international box office; in its first 28 days on Netflix, it was streamed by nearly 40 million accounts, which surely means considerably more than 40 million people watched it. You can do the math on how much box office that would have amounted to had NATO not thrown a hissy fit, which would’ve been a boon to Paramount’s bottom line, too. And only NATO and Paramount have themselves to blame for missing out — and for viewers flocking to streaming.

This fracas is the best example of how Hollywood pushed itself into insignificance. By refusing to make more than just IP-driven merch-movers and denying screens to anything produced by a streaming service, studios and theaters created an opening for Netflix, Amazon Prime, even Hulu and HBO Max to make the mid-budget films that once sustained multiplexes. If Scorsese couldn’t get a gangster picture made at a major studio pre-COVID, what hope did Fletch or Prey have three years later?

Hollywood set itself on fire; the pandemic just accelerated the burn. And now not even streaming services are safe. Warner Bros. DIscovery recently canceled franchise films like Batgirl earmarked for streaming to claim tax write-downs. The narrative of Hollywood has long been intertwined with Wall Street, but the Batgirl decision — and the fates of films like Confess, Fletch and Prey — feel like the opening of a new chapter, one far more insidious than Gulf+Western buying Paramount.

Hollywood is clearly in a period of transition, never easy for the stodgy town, and the pandemic obviously impacted this process. But it also warped something in the machine, or perhaps in the industry’s psyche. It’s going to take a lot more than the second coming of Cinemascope or Easy Rider to set things on the right path — or, at least, one friendlier to audiences, those selfish ingrates.

Releasing movies in movie theaters is a good start, though.

One Comment

Another great column!