In February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that progress has stalled in the effort to end the United States’ HIV epidemic: after five years of substantially declining rates of HIV infection, the number of annual infections has stabilized.

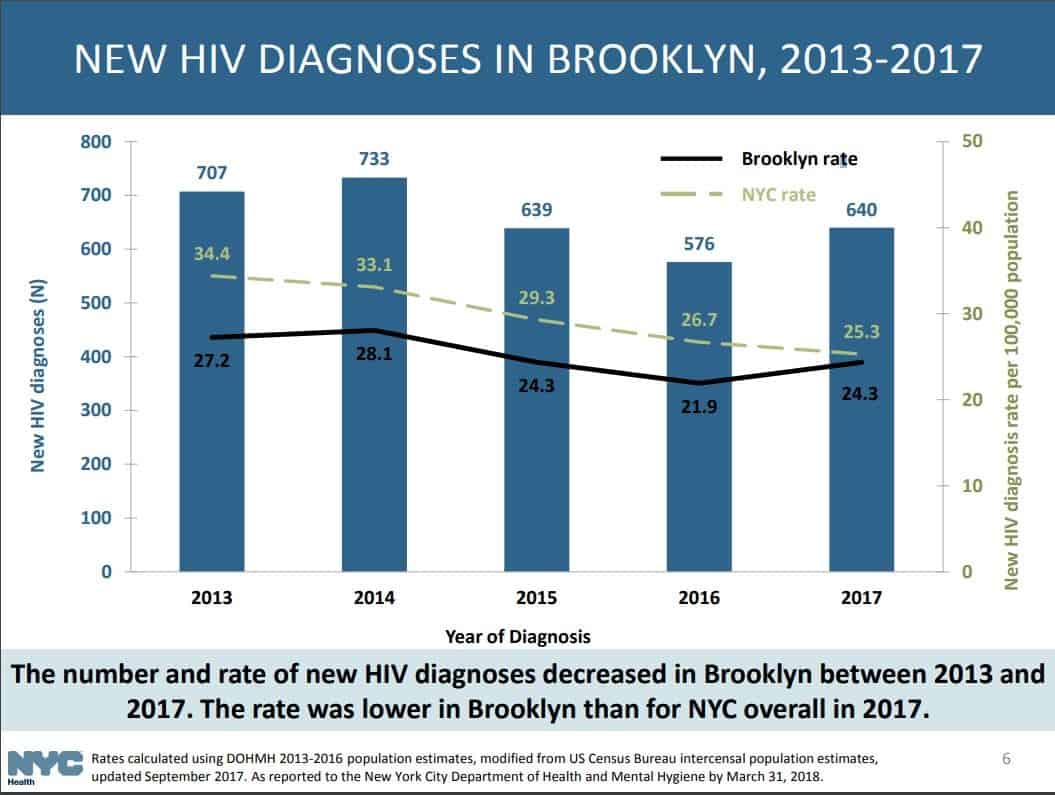

Three months earlier, The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene released a study showing a similar trend locally. The data, which tracked HIV diagnoses between 2013 and 2017, showed a significantly smaller decrease between 2016 and 2017 than in prior years.

In Brooklyn, the number of HIV diagnoses actually went up in 2017, from 576 to 640. No other borough saw an increase. The study also exposed the vast discrepancy in HIV rates between rich and poor New Yorkers. In 2017, areas with very high poverty saw 33.8 new HIV diagnoses for every 100,000 residents; in areas with low poverty, the figure was 9.5. Once infected, poor people, as well as black people, are more than twice as likely to die from AIDS than others living with the disease.

“This illness is impacting people of color more than other populations – in particular, black and Hispanic men who have sex with men,” commented Dr. Isaac Dapkins, the Chief Medical Officer of the Family Health Centers of NYU Langone, which has clinics in Park Slope and Sunset Park, among other locations. “We’re seeing increases in that population, and trans women as well.”

Dapkins advocates for pre-exposure prophylaxis – better known as PrEP, the antiviral drug prescribed under the brand name Truvada to HIV-negative adults who have a higher-than-average risk of contracting HIV through sexual contact or injection drug use.

“The message about this as an option really hasn’t made its way out into the community,” Dapkins lamented. “A lot of people may be suspicious of taking medicines that are associated with HIV before they are HIV-positive and may not necessarily understand how high their risk is. It’s an incredibly effective way to decrease your risk.”

According to Dapkins, NYU Langone’s Family Health Centers use “peer navigators” to “get the word out” about options for patients. Dapkins described a peer navigator as “someone who’s from the community, who speaks the language, who understands the culture of the folks we’re trying to target, and they’ll be working on our staff and spending time in the community, going to events, going to parties, being present where people are in their everyday life and communicating in that setting.”

Dapkins acknowledged that PrEP “is a medicine that costs a lot of money if you’re going to buy it yourself, so there are programs that are available to help people get access” to the medication. Medicaid “is a great coverage for PrEP,” but at the Family Centers, uninsured and underinsured patients can apply for PrEP-AP, a New York State Department of Health program that provides financial assistance for prophylactic care.

The Family Health Centers also see patients who’ve contracted HIV or suffer from AIDS already. Dapkins noted that HIV-positive people see increased risks of certain cancers and cardiovascular disease. “The most important single thing that anybody can do is to know their status,” Dapkins affirmed. “Getting that particular test can be done pretty much anywhere.”