There are three quiet plotlines in HBO’s formally exuberant if politically acquiescent documentary “The Price of Everything.” It opens to a fast-talking auctioneer at Sotheby’s, seamlessly reaching one million dollars for a painting, wielding “masterpiece” around as to indicate a prime cut steak. There are quick defenses of the art market: commercial value means these pieces will survive; art and money have always walked hand-in-hand; work that sell well point the way toward other artists.

We follow through the characters of dealers and buyers and collectors, none of whom are clear villains or saints, up through an auction months later at Sotheby’s where a Gerhard Richter painting is looking at fetching 20-30 million.

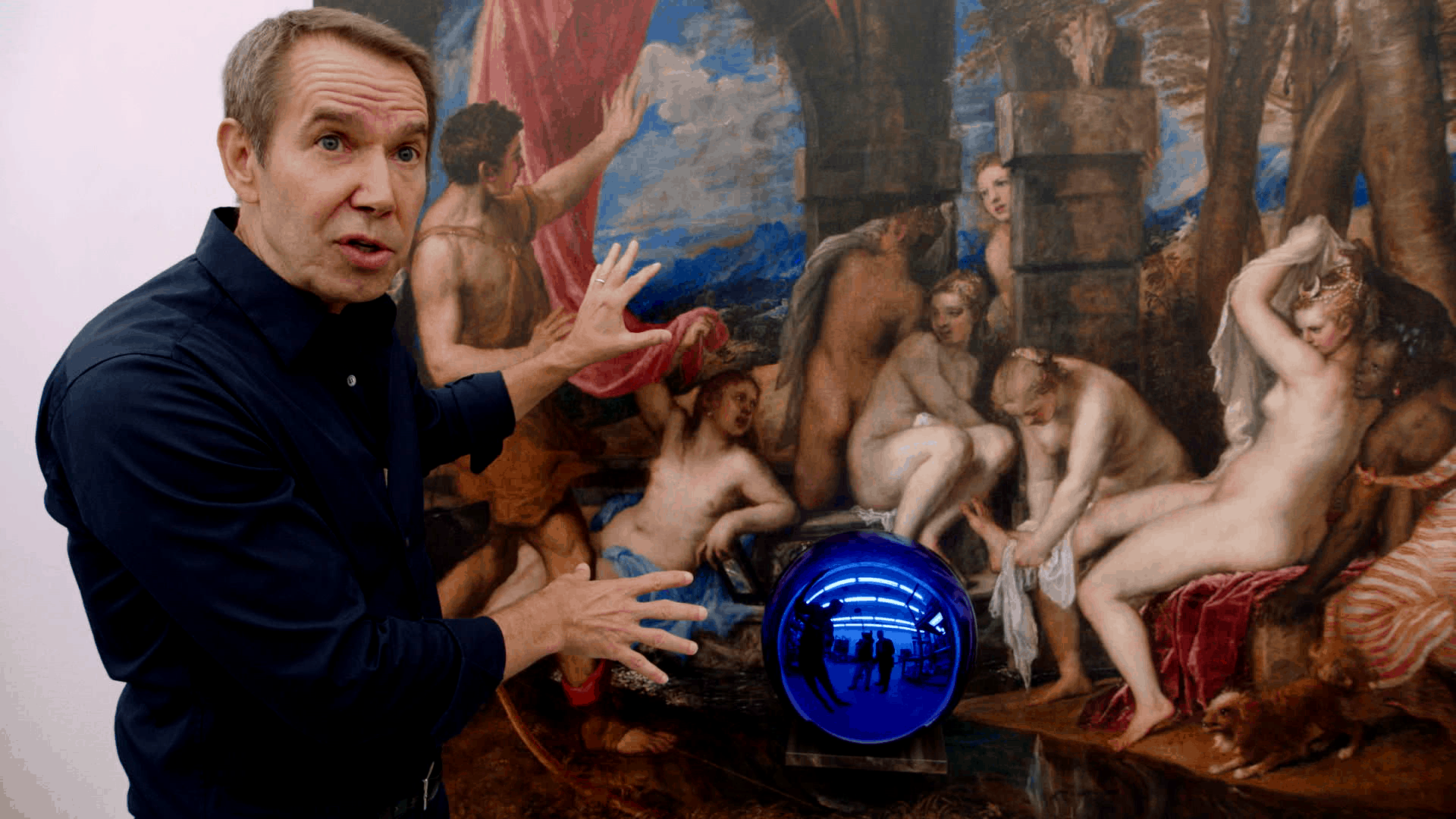

Next up is the artist’s artist Larry Poons, who chose to leave the Jasper Johns-Rauschenberg pack to develop another language of his own upstate after the infamous 1973 Scull auction. Poons is to have a sort of comeback gallery at Yares Art in Midtown East. While preparing for that exhibition, his career and worldview is compared to the mega art star Jeff Koons.

Director Nathaniel Kahn plays up the Koons-Poons similarities and dissonances not only for pleasurable rhyme, but also to trigger some cutting social insight. Both artists received rewards for their art in childhood; in college, their art was critically acclaimed. One has a net worth of $200 million; the other is like most American artists, i.e. poor. Koons acts as a studio manager directing assistants as they replicate famous paintings; Poons does it all by himself, sometimes with his wife watching. Koons handles well in board rooms; Poons won’t walk into one. Koons loves metaphor, speculation, finance; Poons wants the tangible. Koons welcomed branding; Poons abhorred it.

The third storyline follows art collector Stefan Edlis. Having bought early into Johns, Warhol, and Koons, Edlis amassed an astounding collection, spending a few thousand on works that would grow to be worth $10-64 million. Edlis shares some tricks of the trade (never buy pictures with fish; a propensity of red is better than swaths of brown).

The documentary weaves the viewpoints of art critics, historians, and artists on one side, and dealers, collectors, and sellers on the other. Contemporary art, like the Maurizio Cattelan pieces that Edlis collects, has become a luxury brand, according to art historian Barbara Rose; the implication is that art that most people hear about has lost its soul.

Though it’s probably more complicated than that, and “The Price of Everything” loves complications. Edlis, whose Jewish family escaped Germany in 1941, shows “Him,” a kneeling statue of Hitler. When asked how he squares his heritage with this piece, he says calmly “art is art.” Is this a banker’s surgical ability to separate morality from money? As the documentary progress, his actions show it’s more of a respect for art. Edlis donates $400 million worth of his private collection to The Art Institute of Chicago. As the Sotheby’s auction approaches, he quotes the Oscar Wilde line, “Most people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” It’s a fitting name for the documentary and hints that in this inflated world of art valuation, he’s in on the joke. Even as Edlis is involved with an art market that makes one artist rich for every 999 who are poor, he remains a grandfatherly, amiable figure.

For most of its running, “The Price of Everything” is a documentary in the literal sense of documenting a phenomenon. Once can’t help feel that there’s more to be done here: a point of view, a thesis, an opinion. Is simply documenting extreme racial, gendered, and economic inequalities, even in an enjoyable narrative like this, a form of complicity in an unjust system? Probably. But then there’s the fact producers Debi Wisch and Jennifer Blei Stockman used their connections in the rarefied art market to show it as it is. Perhaps exposure is enough of a commentary. Anyone who values art for expression over profit will be irked to infuriated by this unveiling.

In any case, it certainly won’t charged with hitting racial, class, or gender concerns too overtly. The documentary interviews one person of color, the Nigerian artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby, who appears in the context of the film as a younger artist whose going-price is rising rapidly. Through the commercially successful artist George Condo, there’s a too brief anecdote of Jean-Michel Basquiat dealing with feelings of being the token black guy and how that negatively impacted his art. But for the most part, the only people of color are behind the welcome counter at Frieze or putting up wallpaper in a new exhibition.

This is a thoughtful look at how the art market injects concerns foreign to the art process: the need to produce, the stress of fluctuating of pricing, the need to perform rather than create. Most of the artists interviewed – Crosby, Condo, Poons, Marilyn Minter – ignore the art market altogether. Condo, whom a Sotheby rep calls a darling of the market, sums up the disparate spheres: “the art market is really a separate entity. It doesn’t have anything to do with the creation of art.”

During this interview, Condo completes a piece that, as the credits roll, will be packaged and shipped to a warehouse in Queens. This is a fear both sides of the aisle vocalize—that art will be kept in storage to become an abstract instrument of finance, rather than a personal and social exchange of energy and growth. But as the art market’s bubble continues to inflate, more works will be bought just to bolster one’s assets.

There is some satisfaction when, near the end, Chairwoman of Fine Art at Sotheby’s, Amy Cappellazzo, repines that Jeff Koons is becoming lobby art, a fate that can’t be changed. And when the art collector Gavin Brown admits overvaluation is likely: “I think can small smoke.”

The documentary’s stance is subtle, but clear by the end. While the art market is volatile, the art world – typified by artist’s focused on art – is lasting. Poons gets the last words in the film: “It’s the paintings that motivate everything.”