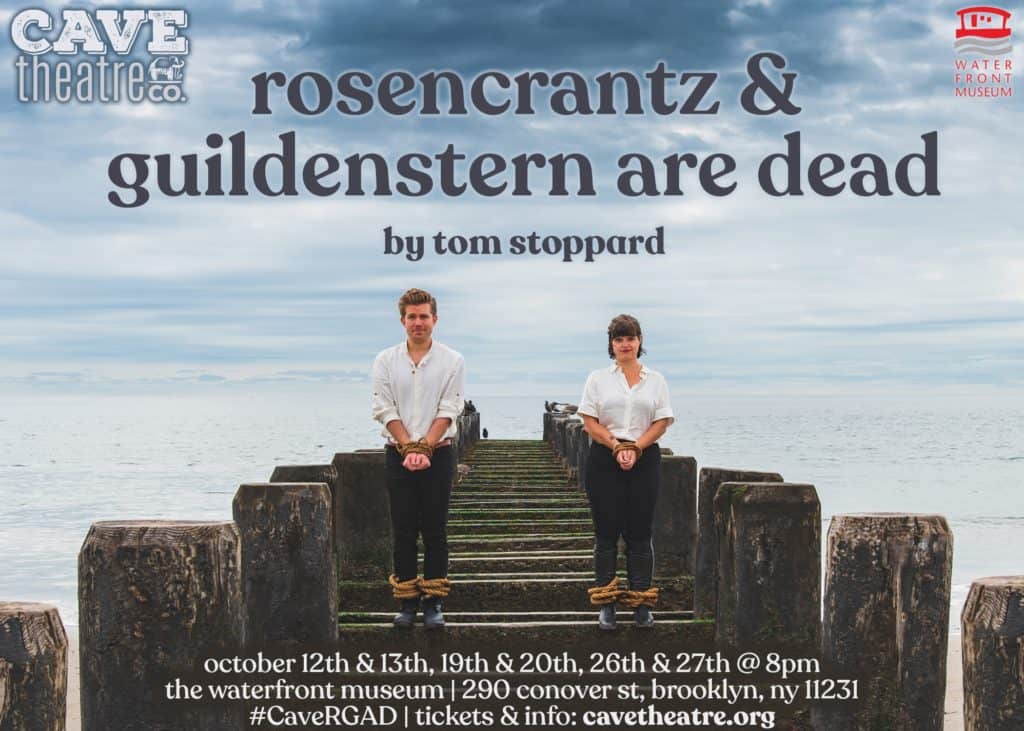

For a month-long run at the Waterfront Museum & Showboat Barge, the Bushwick based theater troupe, Cave Theatre Co., is giving a solid production of “Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are Dead,” the 1964 Tom Stoppard absurdist comedy whose characters, plot, and meaning are all wrapped up in its title.

After the Waterfront’s ship captain removed the plank, and rang a bell a few times, the play began. The first act opens to an optimistic and quaint Rosencrantz (Alex Etling) and the more dour and strategic Guildenstern (Jessie Atkinson) figuring out what’s their role in this play. They’re dressed in McDonalds colored vests and slim messenger pouches, which somehow makes them look serious and superfluous. The stage (and audience) float on a barge that’s lit by three parallel standing lamps that are flicked on and off in various waves to great effect, particularly at the end when the play’s more terrifying themes are focused.

The two blab on, mixing up their names and their roles in whatever is this thing they’ve found themselves performing. Rosencrantz says they should just choose a direction — any direction — to go to find Hamlet. Guildenstern says their minds are too arbitrary to make such lasting decisions. It’s an enjoyable ride if Heidegger is your thing, but Stoppard’s wordplay, allusions, and winks are so unremitting and commanding, that there’s only so much a cast can to do make the play their own and an audience can do to feel like they’re not in a philosophy seminar.

The themes won’t stop: death, agency, authenticity, dramaturgy, memory loss, obligation, friendship, betrayal, psychic torment, human connection, emotional opaqueness, feeling overdetermined. Through this sled ride of constant questioning, Stoppard asks what are the limits of theater; how is “Hamlet” both immensely foolish and terribly wise; how can we laugh through the unsavory matter of being human?

Speaking of which, the hilarity of a mad Hamlet is brought out in full relief by Esther Ayomida Akinsanya’s portrayal of the vaping, giddy, sunglass touting, prince of Denmark. Khalid Bilal’s Claudius was boisterous, ludicrous, and fiercely alive, a welcome spark in Stoppard’s lecture hall.

It’s best when the actors go full out maniacal. The player (Arshia Panicker) was an easy favorite in her unrestrained melodrama that was (in Stoppard fashion) unceasing. When she cries out “We, are, actors!” the tragic side of the play clarifies: they (and we) are actors hooked to a play, hooked to fate.

Despite Stoppard’s overwhelming hand, there are personal flourishes here. Beside the neat fact that much of the play is set on a ship and now the audience is literally on a ship, Gertrude has a beard. They players are hilarious when requiring more action they cry “fire!” to desperately perform for the audience.

At 2 hours and 15 minutes, it’s impressive how seamlessly the actors delivered their cerebral lines, yet it was visibly tiring on the audience. When Stoppard wrote the play, it clearly broke down so many conventions that people couldn’t look away. Now, the tricks are rather routine, and without some editing, can feel tedious. Director James Masciovechio did a fantastic job blocking characters to emphasize various aspects, but an abridged version (with shorter coin tosses at least) may be appreciated, even among the most stalwart of theater-goers.

Ultimately, it’s Stoppard’s eye that comes out full force. The audience can’t get away from that cerebral sensation that they are being watched watching a play. The actors (and audience) are beholden to Stoppard, so much so that the production doesn’t gain its own voice or point of view. But I guess you can say that’s the point.

Through Oct 27 at Waterfront Museum. Ticket available here