It is 7 am, it is freezing, and Frances Medina, 23, is up. She’s sitting at the computer in her mother’s apartment in the Red Hook Houses, and she’s connecting herself to the pipeline of information about Red Hook. She looks at the Twitter feeds of local activists, friends and the kids she mentors with Red Hook Initiative (RHI). Then she reaches her hand out—questioning others, posting her own informational column and following up with donors lined up in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.

At 10:45 am, Frances disconnects, but only from her online vector. She steps into the cold, locks the door and goes to Baked for iced coffee—her preferences don’t change with the seasons. It looks like an indulgence for someone who “likes to take her sweet time in the morning,” as she says. By 11 am, she’s reported to work at RHI.

There, even now, Frances is busy carrying out an immense workload left by the hurricane. In her office—or any office, as offices in RHI are mixed domains, and tend to be shared—she answers calls. “Her people,” or those in the community of Red Hook, ask about how to put on a benefit for RHI, or how to get involved in the organization’s volunteer corps. They call about donations they want to make, and Frances applies a dampener to suggestions of items no longer needed—“No, we don’t need more hats and scarves, thanks!”—even while she culls the items that are needed by firing the stove online—“Where’s my food? Can we get some mac n’ cheese?”

When activists, reporters or representatives from other organizations knock on RHI’s door to ask how they “did it”—how the Initiative stemmed the inundating tide of Hurricane Sandy’s damage to the Houses, replacing it with the balm of food, medicine and other supplies, to national acclaim—Frances answers their questions. She regales them with stories while keeping an eye on “her kids,” or the more than 200 young people between middle school and their early twenties that RHI mentors and provides programming for on a daily basis.

“I am the ‘Sandy Relief Person’,” Frances tells them. What she doesn’t often tell people is that her story has an arc of its own.

Geographically Inclined

Above RHI’s lobby hangs the kind of thoughtful combination of caulking and insulation that precisely resembles a creampuff or a meringue. After briefly checking in with me on the concrete ground floor, Frances attends to point A and point B—two people between her and the metal-grated stairwell—before ascending the stairwell to finish point C—perhaps a phone call.

When she returns, we buzz along another vector to the sole unoccupied office, following RHI’s ambiguous arrangement, which is down the back hallway. When Frances sits down, she begins.

Frances grew up in Red Hook, and she grew up within limits. Red Hook; red tape. Finances, energy and strict lack of awareness of what lay in the rest of New York City severed entire boroughs from her during childhood. She spoke Spanish with her mother, whose ancestry is Puerto Rican, and conceived of life in Red Hook as merely normal. But as she grew into her teens, she started to understand more and more the reasons why people in the projects might, as she puts it, “victimize our situation” by choosing apathy over action.

But a keen interest in emotional health and the influence of her own younger sister led her to reject that victimization. Following her sister, she became involved with the Red Hook Initiative the same year it began—2002—and looked not only into its services, but into the work she could do for others. RHI founder and co-president Jill Eisenhard immediately took an interest in the energetic 13-year-old. It was Jill who became, as Frances puts it, “not just a mentor, but a second mother.”

In high school, the hummingbird spread her wings to become more beautiful even as circumstances grew more terrible. Her father passed away, and her mother was diagnosed with cancer in quick succession. She continued to be a peer health counselor RHI and helped other students prepare their studies. She headed the yearbook staff at her high school and worked at New York University’s Elmer Holmes Bobst Library. She was still keenly interested in emotional health.

But as she entered the phase of high school where the road gets blurry and then spits out eight forks ahead, Frances despaired. Perhaps she wasn’t meant for college after all—perhaps she should drop the books, drop the illusions and file straightaway for a minimum-wage job instead.

In a time of personal crisis, Frances’ second mother stepped in the void. College, she said, was not one option, but “the only option.” She cited Frances’ “plan,” which all RHI youths use to organize life goals with their mentors. Frances’ plan was one imbued with Jill’s trademark: boldness. And for Frances, the RHI founder extended herself even further to realize that plan. She searched for colleges with Frances, pushed her to complete applications and write essays and finally to enroll at the University of Michigan (UM), an institution Frances hadn’t dreamed of attending.

If Jill and RHI, as Frances says, birthed this opportunity for her, they also birthed in her the spirit of community action. At the University of Michigan, she executed her responsibilities like a student inspired—inspired not to let down Jill, RHI and the creampuff clouds of caulking and insulation of RHI’s ceiling—atop which she bounced into Ann Arbor. She played hopscotch between her academics and various student organizations. She was part of UM’s prestigious Order of Angell, maintained an average GPA above 3.0 and managed to flit between entirely different geographic plateaus.

In 2008, she forfeited her spring break and ventured south to New Orleans instead. While her classmates partied in exotic locales, Frances sorted debris left stagnant in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. She was a college freshman, and she loved it—rebuilding wood, plaster and the root materials of “community”—so much that she returned the following summer.

Outside of New York and the pressure to perform in Ann Arbor, Frances eyes’ dilated with a new cultural perception of her surroundings in New Orleans. In bars and on the streets, jazz players sussed out the blues, brass bands swayed and even tap dancers clacked against African beats. The experiences each year were unforgettable, and gave her a taste of what new cultures could be like.

So she played hop-scotch with grant-writing, applying to source after source of funding within the University of Michigan for a new dream she envisioned: two months abroad in Italy during summer holiday, where she could study Italian and nurse a passion she’d long bottled up: drawing, and “living the arts.”

She wrote essays about eating pizza in Italy; she won $16,000 dollars in funding. She walked Italian piazzas and art events—only the free ones, because Italy is expensive—and visited other cities with her program. Then, she got stranded.

When Frances missed her plane back from Italy, she didn’t have the cash to buy another ticket. Michigan had reduced her grant award by $4,000 at the last moment, eviscerating the careful architecture Frances had put in place for her trip. She had no relative to bail her out with hundreds via Western Union.

RHI, which even since high school had been Frances’ “place to get grounded,” brought the hummingbird back along a red vector to the Hook. Getting lost in Italy wasn’t part of Frances’ “plan;” but a free ride wasn’t either. Within months, and on principle, Frances repaid Jill every dime she borrowed for the ticket.

Now, Jill has sent Frances off to explore another vector leading to Africa. Sometime last fall—before the maelstrom of need left by Hurricane Sandy—she pushed Frances to apply for a spot with the Kilimanjaro Initiative, which offers four young people with outstanding leadership records a fully funded opportunity to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro and see KI’s work in Kenyan village communities.

Seated at the helm of RHI’s communications center during RHI’s Sandy Relief efforts, Frances forgot about her application. But KI didn’t; they accepted her. Now, along with just three other New Yorkers, she’s bought climbing gear and a plane ticket.

“I’m literally climbing a mountain—climbing another milestone. I have no idea what to expect. But I am so happy this opportunity is falling into my lap,” she says, smiling at more than serendipity.

Indra’s Net

At University of Michigan, Frances’ first major was sociology, the first class of which she took on a hunch. “Sociology 101 – The Study of Sexuality” marked the first time she’d ever encountered the idea of five different sexes.

She took more sociology classes, which introduced her to the roving positions and roles taken by the members that in turn make up a community. She learned the frameworks and the vectors along which effective community action might take. She learned better writing, which would go far in her later grant applications, and she learned more about her own interest:

“There was a definite trend that I was interested in community,” she says.

It’s this skill for community organization—this mathematically precise intuition about how it can be most effective—that Frances recognizes as her vector to interaction with the other young people accepted into the three-week program. And she believes she’ll fit in well.

“The dynamic of the group going is amazing—we have an artist who’s 18, who does murals in New York and also music, beats and raps. It’s his first trip abroad. We have a current university student who’s just starting to branch out. We have a grad student who brings expertise and has done research before. Really—I can’t wait to watch everything collide and intersect,” Frances says, adding that six Kenyans, similarly aged, will join the group along with the instructors.

When she walks through Kenyan villages, when she interacts with both countries’ young leaders, Frances promises she’ll be “processing, as a sociologist, all my interactions.” In a country so different—so rich with culture, yet so poor, monetarily—she wonders if she’ll have an epiphany of the same sort that brought her knocking at RHI.

“In the projects, we’re prone to victimize our situation. But Kenya won’t be like the projects. Those people have a lot less, and I don’t know what to expect.”

A few things are certain. When Frances returns, she’ll put on a photo exhibit of her trip with a New York arts organization, FOKUS (Fighting Obstacles Knowing Ultimate Success), with which she’s worked in the past. And along with the other New Yorkers going to Kenya, she’ll make a documentary of her experience there.

From there, things become more tangential. She wants to start an arts experiment at RHI, working with her kids to channel their artistic energies into projects like their own documentaries. She wants to write about her time in Kenya. As a sociologist, she wants to calibrate her understanding of Red Hook with what she finds in Kenyan communities—to optimize her algorithm for the different vectors in play at home.

“We need you”

Last year, after graduating from Michigan, Frances tested her limits by working for a number of organizations simultaneously—the Sadie Nash Leadership Project, Los Pleneros de la 21 and, of course RHI. With the hurricane approaching, however, she knew it was time to consolidate her energy.

Even before Sandy struck, she dropped these other obligations and began working full-time in the RHI hub directing donations, communications and human resources. Along with Jill and the other RHI staff, she gave extra energy to make sure all of RHI’s normal programming for kids remained available. Her position, just as before, was listed as part-time.

When she comes back from Kenya, Frances wants to keep working with the kids, namely through the arts project she envisions as an offshoot of her photo and documentary exhibitions. But after so much prodding from Jill to apply to college, go to college; apply to Kenya, go to Kenya—and after so much pinball through the sociology offerings of Michigan and RHI’s own organizational structure—Frances has a plan of her own.

And after seeing, repeatedly, Frances’ organizational alacrity and poise in the wake of Sandy, Jill was ready to accept that plan. “We need you,” was all she said when she gave Frances a full-time job offer.

For the bystander or visitor in RHI’s community center, Frances’ activity must seem frenetic. But her energy transcends the flurry that descends on her after a strong iced coffee from Baked; it is orchestrated.

“I love the kids, but transitioning into RHI’s development aspect is a priority for me. I could work in anything here, say in college retention. But I would work ten times as hard to get this organization running at its best and to get it the money it needs to go on,” she says. “If you have the skill set to keep the organization running, you have to use that skill set!”

And so, when Frances returns from Kilimanjaro, her superchiasmatic monitoring of the Red Hook’s circadian rhythms will be nested with a job title at RHI, perhaps “Development Consultant.” Before then, she has just three weeks to get used to this idea amid the tumult of a new setting.

“I’m just ready to breathe and enjoy other people,” she laughs, a hummingbird whose nectar is community.

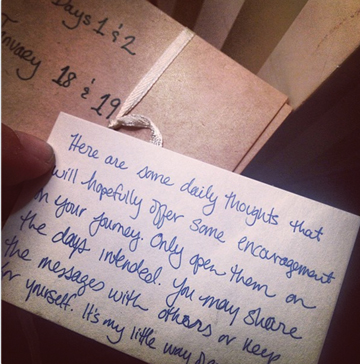

She has three weeks, and a final gift from Jill. As Frances packed to leave RHI on the Thursday before her trip, Jill handed her a set of notes wrapped in brown paper. For each day, she will unwrap one note from the sheaf. For Frances, Jill’s continued advice represents the “best gift,” as she called it on her Twitter feed. On the same feed, less than two months previous, she posted a quote by Anaïs Nin, an author whose heritage was also twined with Puerto Rico:

“And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.”

“I have no climbing experience whatsoever,” Frances says back in the office, her eyes looking a red vector at the sandy brown boots the Kilimanjaro Initiative bought for her. She’s laced them with purple strings. This isn’t her office. She leans back in the chair and grins.